The Map: Get Out the Vote

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/VoterTurnOut2008County003.png)

This is the third of three stories on the political map of Texas going into the November election — a collaborative reporting effort between The Texas Tribune and the El Paso Times. The first centered on the race for governor and what would have to change for Democrats to win in the politically fortified red state of Texas; the second was about Latino voting in Texas and why the state's fastest-growing population has relatively little political clout.

It's a tale of four counties. Two of them are the largest Latino-majority and Democratic-leaning counties in the state, and they rank near the bottom when you compare the size of their voting age population to the actual number of people who show up at the polls. The other two are growing suburban counties with larger Anglo populations that tend to lean Republican and produce some of the highest turnouts of eligible voters anywhere in Texas.

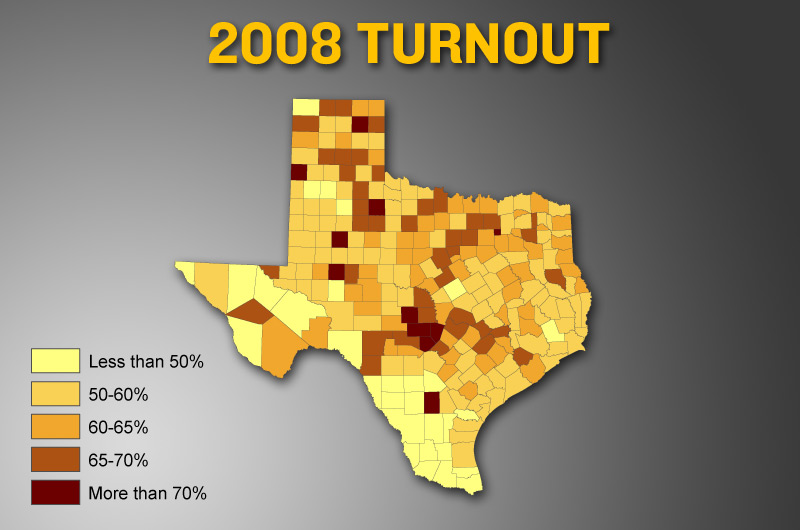

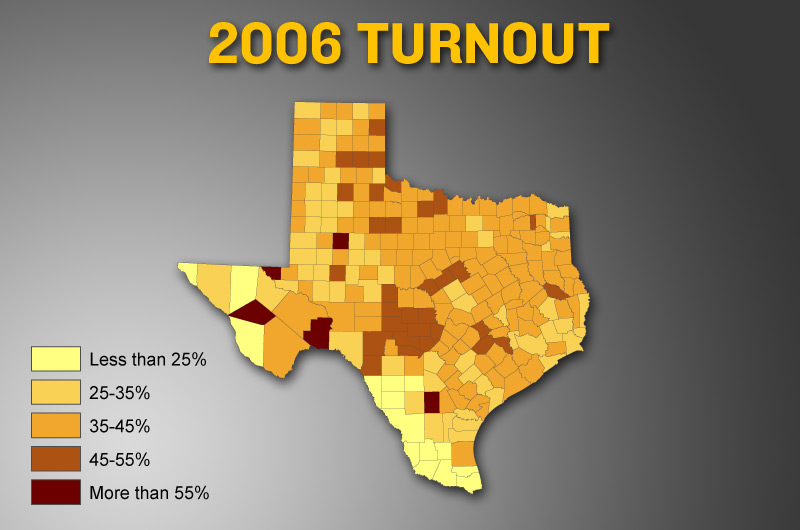

The El Paso Times and The Texas Tribune ranked the state's 50 largest counties by comparing the number of people who were old enough to vote in 2008 and 2006 with those who actually cast ballots. El Paso and Hidalgo counties ranked in the top 10 for the size of their voting age populations but dropped to the bottom 50 in a ranking of their voter turnout. Collin and Fort Bend counties, which are similar in size to El Paso and Hidalgo, were it the top five for their voter turnout two years ago.

It is a dichotomy that surprises few but frustrates many.

The geographic area that forms a triangle connecting the state's four largest metropolitan areas and incorporates Collin and Fort Bend makes up about 66 percent of the vote in Texas. Statewide candidates can focus almost exclusively on the counties within that triangle for the bulk of their votes, which leaves the rest of the state fighting for attention. But many of the remaining large counties that are seeking that recognition from statewide candidates and officeholders are not voting in proportion to their population.

Border counties have often felt neglected by the rest of the state, while the growing suburban communities in Collin and Fort Bend get substantial attention from state-level politicians. Community leaders say some border counties suffer because they are Democratic strongholds in a Republican state — but the party will have a hard time regaining control if its key counties do not flex their muscle at the polls, analysts contend.

Democratic consultant James Aldrete says El Paso and Hidalgo would have more clout if Bill White were elected governor because he needs the support of the two counties to win the office. Republican Gov. Rick Perry, on the other hand, does not have to win either county to secure the election and, if turnout is low, does not have to work to increase Republican voting margins either.

In the meantime, Aldrete says, the border counties struggle because politicians focus on two things: votes and money. “They get ignored because they don't vote and they get ignored to a large extent because there is not the same level of money and influence, and so when bad decisions happen, there are no consequences,” he says.

Collin and Fort Bend leaders say the attention their counties receive is less about partisanship and more about involvement. The counties maintain large numbers of voters and active coalitions of business leaders, donors and community members who lobby politicians at the Capitol. McKinney Mayor Pro Tem Pete Huff says voter turnout and community involvement have given Collin County leverage at the state level. He says community leaders worked out a compromise when a toll road was built in the county. Money for four free roads was provided through the agreement, which would not have happened if Collin did not have political clout from its active participation in elections, he says.

State-level politicians “know who we are and we know who they are and we don't hesitate to call them,” Huff says. “We've had the growth and the success and the voter turnout.”

Huff says his county's involvement in politics can be attributed to educational attainment, income and homeownership. About 92 percent of Collin County residents have high school degrees, and nearly half graduated from college; both percentages are well above the state average. The median household income for the county is nearly $82,000 annually, compared with the state's average of $50,000. And almost 70 percent of residents owned their homes, according to the 2000 census.

A Pew Hispanic Center study indicates that higher voter turnout can typically be found in more affluent areas with better-educated populations. Older populations are often settled and have mortgages, which makes them care more about issues such as taxes and drives them to the polls. Counties that vote in smaller numbers are primarily Latino, have lower levels of education, are younger and earn less money in the workforce, analysts say.

Both El Paso and Hidalgo counties are more than 80 percent Latino. About 66 percent of El Pasoans and about 51 percent of Hidalgo residents graduated from high school. College graduation rates for both counties hover between 13 and 17 percent. The number of people who live in poverty is well above the state average. El Paso and Hidalgo may also have greater numbers of recent immigrants who are not eligible to vote.

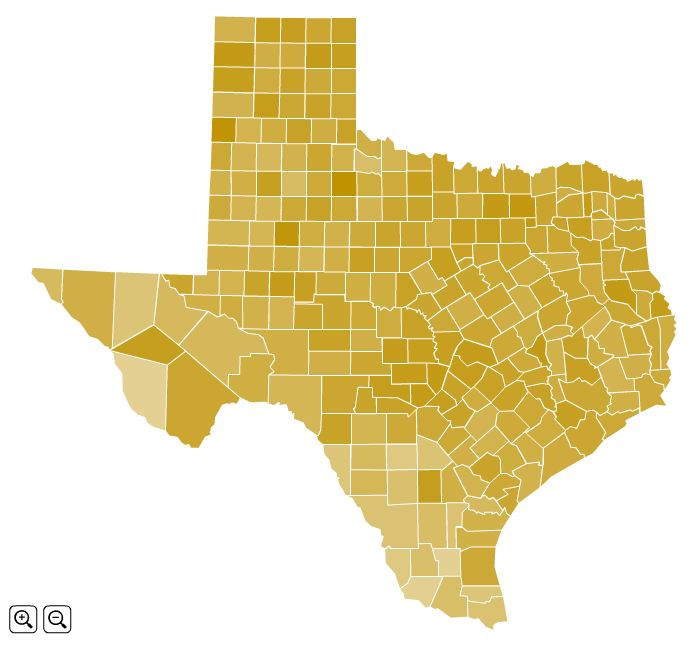

View an interactive map of turnout in the 2006 and 2008 elections.

It is a cycle that is difficult to break and not unique to border communities.

State Sens. Mario Gallegos Jr., D-Houston, and Tommy Williams, R-The Woodlands, represent adjacent districts that are similar in size but vastly different. Williams' district stretches from the upscale Houston suburb where he lives to Beaumont. A quarter of his constituents have college degrees, and three in four of them own homes. Gallegos represents an inner-city Houston district where more than 60 percent of residents don't speak English at home. About half don't have high school diplomas.

Williams, who did not have an opponent in 2008, received 203,000 votes. Only half as many ballots were cast in Gallegos' contested race that year.

University of Texas government professor Daron Shaw says counties often have to wait until their populations grow older, have children and settle down. Those factors, he says, naturally boost voter turnout. Shaw says it is often difficult to pinpoint how to mobilize infrequent voters and that Latino voters may be even tougher to track because analysts are still trying to figure out what drives them to the polls.

“I hate to be pessimistic, but there are limits to what the state can do to facilitate the sorts of attitudes necessary for civic participation,” Shaw says.

Voter turnout is only one factor that draws programs and attention from the state, but it may be the most important.

State Rep. Aaron Peña, D-Edinburg, says passing legislation that would bring additional resources for a community can, at times, be difficult if voters do not flex their muscle at the polls.

“The general deference and respect you get politically speaking comes from the strength of your community,” says Peña, who represents Hidalgo County. “If your community does not speak with its full voice, that's taken into consideration.”

Many believe that lower turnout in Latino communities also tends to hurt the Democratic Party, which is trying to reclaim control of Texas politics. Democrats typically have an advantage with Latinos in Texas, but it does not help them win statewide office if those voters are not turning out at the polls.

According the analysis by the Times and the Tribune, El Paso would have had about 117,000 additional votes if the border community turned out at the same rate as Collin County in 2008. Of those votes, nearly 72,000 could have gone to the Democrats if the new people voted like those who already showed up.

Hidalgo would have had more than 76,000 votes if residents cast ballots at the same rate as Fort Bend. That could have been a gain of about 45,000 votes for Democrats in Hidalgo two years ago.

Peña says some politicians disregard Democratic counties that turn out in lower numbers. He recalls the bitter battle between Democrats and Republicans in 2003 over redistricting: Democratic lawmakers felt that they were being trampled on as the state redrew political boundary lines and warned Republicans that the tide could soon turn. “Their response was, 'Well, based on your voting numbers and the percentage of people turning out that won't be for a long time — it will be after our lifetimes,'” Peña says.

Counties that produce more voters often reap the benefits of such participation, experts say. During election cycles, candidates seeking statewide office will often make promises for additional money or better roads to keep those voters and donors happy.

State Rep. Charlie Howard, R-Sugar Land, says Fort Bend has built a reputation that makes it difficult for state officeholders to ignore. Howard says his county, which sits south of Houston, is made up of educated residents who are not afraid to voice their opinions at the ballot box or in person. About 84 percent of residents in Fort Bend County graduated from high school, and 37 percent have college degrees. Both percentages are larger than the state average.

“I will assure you that the governor, the lieutenant governor and the statewides all look at Fort Bend County,” Howard says. “They all come to Fort Bend County. They want to be here in front of my constituents because they know they are going to vote.”

But counties like El Paso and Hidalgo have some recourse to attract statewide attention. El Paso Mayor John Cook says that while voter turnout in El Paso may be “dismal,” community involvement has helped the Democratic city earn respect in a Republican state.

Cook says El Paso business leaders and community members have worked hard to get the city the recognition it normally would not be afforded. He says in many ways El Paso has contributed to a "pobrecito" ("poor us") attitude because it never stood up for itself and often let others define the city. But now city leaders are members of state and national groups that draw attention to the area, he says. And business leaders have greater access to state-level politicians because they are key donors and fundraisers for campaigns.

“It becomes harder for the folks at the state to ignore you if the rest of the country is paying attention to you,” Cook says.

State Rep. Joe Pickett, D-El Paso, says low voter turnout does not affect a county's clout in the Legislature but could hinder its leverage with politicians who are elected on a statewide ticket. He said that for the most part, the projects and money a community gets from the Legislature are based more on need and the relationships and the work of its elected lawmakers.

On the other hand, he says, the statewide elected officials would likely look to help counties that offer the most votes to get them in office. “I hear a lot of times, 'Well, if we voted more in El Paso, Austin would listen to us,'” Pickett says. “I don't know who Austin is. Austin is just where all of us from around the state get together to discuss issues.”

Elections administrators for El Paso and Hidalgo counties say there is always room to improve but that residents are casting ballots in greater numbers than ever before.

“It will always hurt us that we have such large counties in terms of population but not as large a voice as we could have,” says Yvonne Ramon, the elections administrator for Hidalgo County. “When our community starts to realize how strong we can be, then wow, watch out.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/TxTrib-Staff_0016_StilesMatt800.jpg)