Aggie Years Launched Perry — and a Rivalry

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/AM-Perry.jpg)

COLLEGE STATION — When Rick Perry arrived at Texas A&M University in 1968, it was at the end of a summer in which Soviet troops crushed the Prague Spring, protesters at the Democratic National Convention were met by a police riot and the United States reeled from the twin assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy.

With its conservative culture, military tradition and focus on agriculture, few places in the U.S. might have seemed more insulated from the prevailing currents of the age. But A&M was in the midst of its own political awakening.

Facing falling enrollment, the school had begun admitting women and had made participation in the ROTC-like Corps of Cadets — long mandatory at this military academy — optional. This created a sudden and deep divide on campus between the civilian and military undergraduates. Many corps members shunned civilians (one corps leader even forbade them from speaking to non-corps members), and civilians sought student government posts to encourage the changing climate.

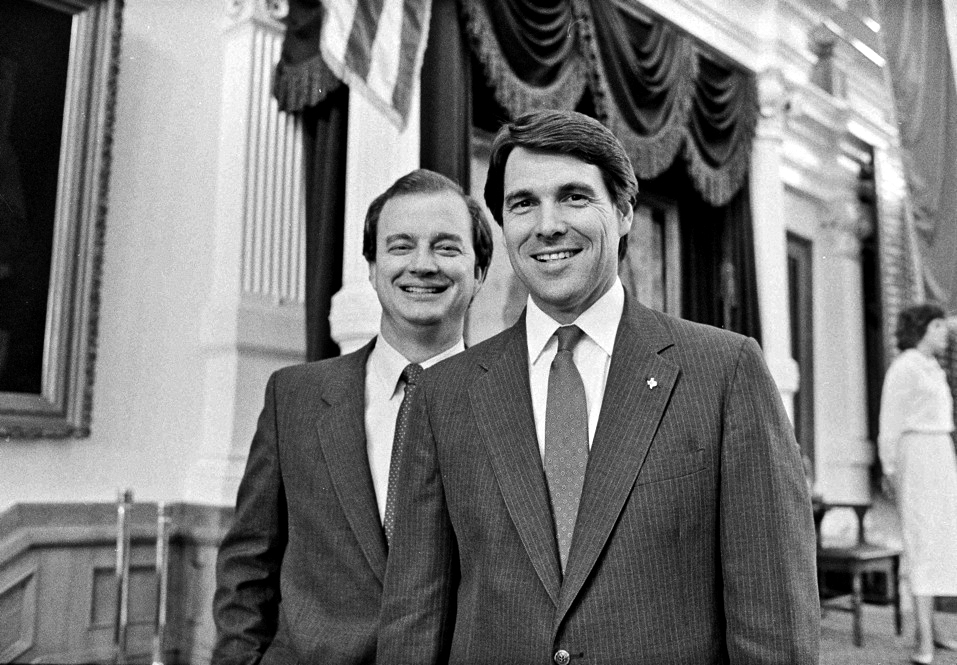

Among these civilian reformers were several future Texas politicians: Garry Mauro, who would go on to serve as land commissioner and was a Democratic nominee for governor; Chet Edwards, who would become a state senator and then a U.S. congressman; and Kent Caperton, a future state senator. They found a like-minded ally in the corps: John Sharp, who would serve in the Texas House and Senate, as a railroad commissioner and as the comptroller of public accounts. But not Rick Perry.

Perry, who decades later would serve in the Texas House, as agriculture commissioner and as lieutenant governor before becoming the first A&M graduate to occupy the Governor’s Mansion, was a staunch traditionalist devoted to the corps. When he finally won elective office his senior year — he’d been prohibited from doing so before because of scholastic probation — it was thanks to the votes of his fellow cadets.

A spokesman for the governor said A&M is very important to him and "helped shape who he is today."

Sharp told The Texas Tribune in June that, as a young A&M cadet alongside Perry, nothing was further from their minds than national politics.

"We were insulated from all that stuff," Sharp said. "You've got a whole lot of things on your mind other than national politics, like how to get breakfast in the morning without getting chewed out.”

College pranksters

Despite their opposing views, Perry’s time at A&M was defined in part by his relationship with Sharp: The two were in the same outfit of the corps and lived on the same floor of their dorm for three years. Their friendship would evolve into one of the great Texas political rivalries of the 1990s when they faced off in the 1998 race for lieutenant governor.

In a joint 1989 interview with the Abilene Reporter-News, Sharp recalled meeting Perry for the first time freshman year.

“When I first saw him, I thought he looked stupid,” Sharp said, referring to the regulation haircut that Perry had received as a freshman corps member. He told Perry so.

As buddies and corps compatriots, Perry and Sharp’s relationship was at first more mischief-making than politics. If you believe Sharp, it was Perry whose ingenuity and disrespect for seniority led to the most memorable stunts.

“Rick chose his targets pretty carefully. If he chose you, it was a pretty good clue that everybody else hated you, too,” Sharp told the Reporter-News. “Perry just did it with a lot more style.”

On one occasion, Perry put live chickens in the closet of an upperclassman and left them there during Christmas break. “You can just imagine the smell,” Sharp said. “Needless to say, he didn’t mess with Perry again.”

Another more elaborate prank took Perry months to execute. It involved M-80 firecrackers and an acquired knowledge of the plumbing in A&M buildings.

Perry learned that he could drop something down the second floor toilet and get it to come out the first floor toilet. Then he learned M-80s had waterproof detonators — a perfect combination. His accomplice, Sharp, would give the high sign out the window when a potential target wandered into a stall. Perry, from the floor above, would flush the lit firework down.

"It kind of launched the guy off of the seat,” Sharp told the Tribune in June. "It was quite a hoot. It was one of our more perfect deals.”

But Perry wasn’t the only one with success in hijinks. In a 1988 interview with the Reporter-News, Perry recalled how Sharp, at a stoplight in Hillsboro, once intimidated a group of motorcycle thugs by eating live crickets.

Political rivals

By their senior year, Perry and Sharp had run each other's campaigns and ended up in different places. Sharp was student body president, working to reform the campus to make it more hospitable to civilians. Perry was elected a yell leader — an esteemed male cheerleader who has traditional responsibilities at major athletic events — and social secretary for his class. And he was exceedingly loyal to the corps, which he credited with giving him the discipline to get an animal sciences degree — his 2.5 grade point average wasn’t high enough to go the veterinary route — and join the Air Force.

“I was probably a bit of a free spirit, not particularly structured real well for life outside of a military regime,” he said in the 1989 interview. “I would have not lasted at Texas Tech or the University of Texas. I would have hit the fraternity scene and lasted about one semester.”

Sharp’s position — student body president — may have seemed a better predictor of a career in politics. Perry saw it another way. “Really, being yell leader had more political consequence than anything else,” he said. “It was really visible.”

The distinction between substantive roles and visible roles would rear its head again: After stints as an analyst for the Legislative Budget Board, a state representative and a senator with policy-heavy positions, Sharp sat on the Railroad Commission and later became the state comptroller. Perry served as a state representative and, after switching from the Democratic to the Republican Party, as agriculture commissioner, allowing him to build on his rural base. By the early '90s, with both men elected statewide, a competitive edge surfaced. The agencies run by Perry and Sharp repeatedly came into conflict. On one occasion, Perry even interrupted Sharp’s press conference.

"If you're running against Rick Perry," Sharp said in his June interview with the Tribune, "you better bring your lunch."

By the time the two Aggies took each other on in the close 1998 race for lieutenant governor, Perry’s high profile, combined with shifting political tides, made him formidable. Less than two years after winning that contest, Perry was headed for the governorship. And six years after that, the two reconciled after striking up a conversation in an Austin gun store. Perry and the Legislature were struggling to pull together a school finance package. He turned to Sharp, putting him in charge of a blue-ribbon task force of business leaders and others. That panel devised a controversial package that lowered local school property taxes and replaced them with a new business margins tax. The governor got anti-tax activist Grover Norquist to bless the idea, while Sharp convinced the business community. In special session in spring 2006, the two got the Legislature to bless it. The tax remains controversial — many blame it for the recurring $5 billion annual hole in the state budget — but the changes forestalled lawsuits over school finance, and the two old friends turned rivals turned friends have remained close ever since.

Mauro, now an attorney, said that of all the student leaders he dealt with at A&M, Perry was not the one he would have expected to become governor. “Anyone that isn’t kind of in awe of what he’s done is jealous,” he said.

But in the 1989 interview with the Reporter-News, Sharp said A&M was the ultimate political training ground.

“I’ll tell you this,” he said at the time. “Politics outside A&M was much easier than politics inside A&M. It was a microcosm."

Jay Root contributed to this article.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/tt-headshot-chris-hooks.jpg)