Abundant With Natural Gas, State Eyes More Oversight

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/TxTrib-NaturalgasRig-ES-04.jpg)

KENEDY — At a packed meeting here one evening last week, natural gas industry boosters told long tables of ranchers and townspeople about anticipated jobs and economic opportunities. Outside, along lonely country roads near town, lights from drilling equipment glittered in the dark night.

Kenedy sits in the heart of the Eagle Ford Shale, one of the largest and most recently discovered oil and gas fields in the state. The first gas well was drilled just three years ago, and the yields of Eagle Ford are part of the reason why production of natural gas in Texas — the leading gas-drilling state — is projected to keep rising.

“Really, the future for the commodity has never been brighter,” said David Blackmon, the chairman of the Texas state committee for America’s Natural Gas Alliance, which organized the Kenedy meeting. Already Texas produces close to one-third of the natural gas in the country, and Blackmon’s organization is eying ways to increase utilization of the fuel, in power generation and in fleet vehicles.

Yet the state’s renewed commitment to gas comes at a time of sharply increased scrutiny for the gas industry. Gas burns more cleanly than coal, its chief rival in electricity-generation. Gas prices have also been low in the past few years, which is good for the power and home heating sectors and manufacturers like fertilizer plants that also use it.

But the recent surge in drilling, including the expansion of a method called hydraulic fracturing that involves shattering rock thousands of feet underground with a combination of water, sand and chemicals, has prompted lawsuits and complaints by some homeowners in Texas and in other parts of the country about contamination of aquifers, as well as concerns about the sheer volume of water needed to operate a well. The industry denies that hydraulic fracturing, by itself, can contaminate aquifers. But worries about air pollution from drilling operations have also stirred anger in the Barnett Shale around Fort Worth, the earliest of three major Texas shale formations to be drilled (the third formation is the Haynesville Shale, in eastern Texas stretching into Louisiana).

In Texas, these concerns have led lawmakers, particularly those from the Barnett Shale region, to file a number of bills to increase oversight of the industry, spanning issues like emissions from wells to the safety of gas pipelines.

With the state facing a $15 billion to $27 billion budget gap, gas industry executives are also wary of attempts to end a 22-year-old tax break for high-cost natural gas drilling, which includes hydraulic fracturing. State Rep. Lon Burnam, D-Fort Worth, just introduced legislation to do so, which would bring in $2.3 billion for the state over the biennium. The tax break was intended to jump-start the industry, Burnam said, and “we don’t need it anymore.”

But Blackmon, of the natural gas group, said that it would drive some planned investment out of state, adding that the industry already pays billions in taxes on the state and local levels.

A century ago, in the early days of the Texas oil boom, natural gas was considered a waste product and flared or vented off. But after a giant gas field was found in the Panhandle in 1918, Texans began using the fuel to manufacture carbon black, which is used to make car tires. Eventually, Americans began using gas to heat their homes, and, later, to fire power plants.

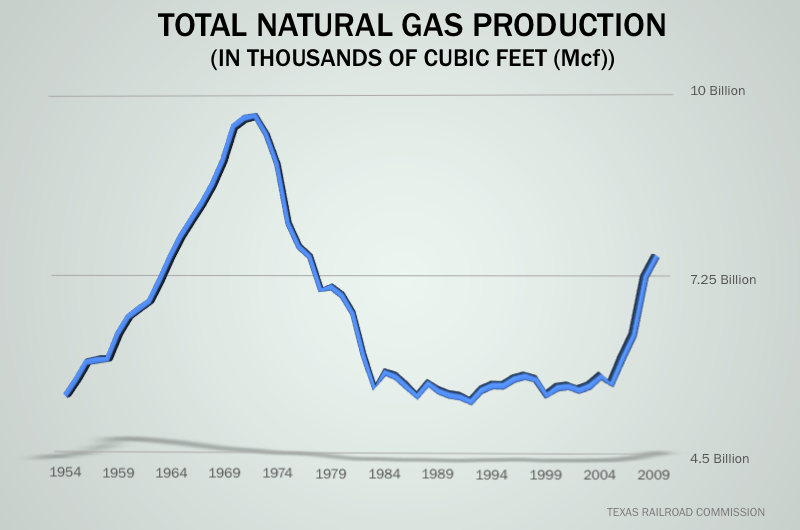

Texas natural gas production rose steadily until it peaked in 1972, the year before the oil embargo. Since 2005, the widespread use of hydraulic fracturing has caused Texas gas production to begin to climb again, though production is still well below 1972 levels.

Today, Texas uses most of its gas in state, according to Blackmon, who said that Texas consumes about 25 percent of the nation’s gas. About one-third of Texas homes are heated with natural gas or propane, and the Texas grid gets 38 percent of its electricity from natural gas (more than the 23 percent average nationally). However, the share of gas has declined slightly in recent years due largely to rapid spread of wind farms in West and South Texas. Because gas plants are easier to turn off and on than coal and nuclear plants, wind has eaten into their share — something Blackmon said he is concerned about.

Gas’s share of Texas electricity production is becoming a political issue. Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst recently said he would prefer old coal plants be replaced with natural gas over the long term. However, energy experts say this would be expensive and difficult to achieve in a deregulated market, where power plants essentially control their own fate.

Meanwhile, the drilling will continue, even though prices for natural gas are lingering at one-third of their highs of three years ago (the turmoil in the Middle East has so far had little impact on gas because it is domestically produced). But the controversies over drilling’s impact on water and air pollution seem poised to intensify, as drillers reach new areas in the Eagle Ford Shale.

Jen Powis, the Sierra Club’s senior representative in the Texas region, said, “These big three shale plays are presenting a huge problem” for local communities, in terms of air emissions and water damage. She added that Texas regulators have been too lax in cracking down on air and water pollution, and that Texas’s problems are going “sort of going unnoticed,” in contrast to the loudly aired pollution concerns in other drilling states like Pennsylvania.

One major Texas case in which the federal Environmental Protection Agency accused a driller, Range Resources, of contaminating two water wells in Parker County, remains embroiled in litigation. Texas Railroad Commission examiners, conducting their own investigation, recently recommended that the commission clear Range (which denies the EPA's allegations) of harming the wells.

Attendees at last week’s meeting in Kenedy emerged with varying views on gas.

“I think it’s a clean fuel, and I’d rather see it than the coal,” said Ed Wollny, a retired transportation-industry worker in Wilson County.

But Sharon Owens, who has a cattle ranch in Wilson County, said, “I don’t think people are thinking. Would you rather be able to drink water, or would you rather have gas?”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/TxTrib-Staff_0013_GalbraithKate.jpg)