At Public Universities, Graduation Rates Lag. But Do They Matter?

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/CompletionCrisisLeadArt.jpg)

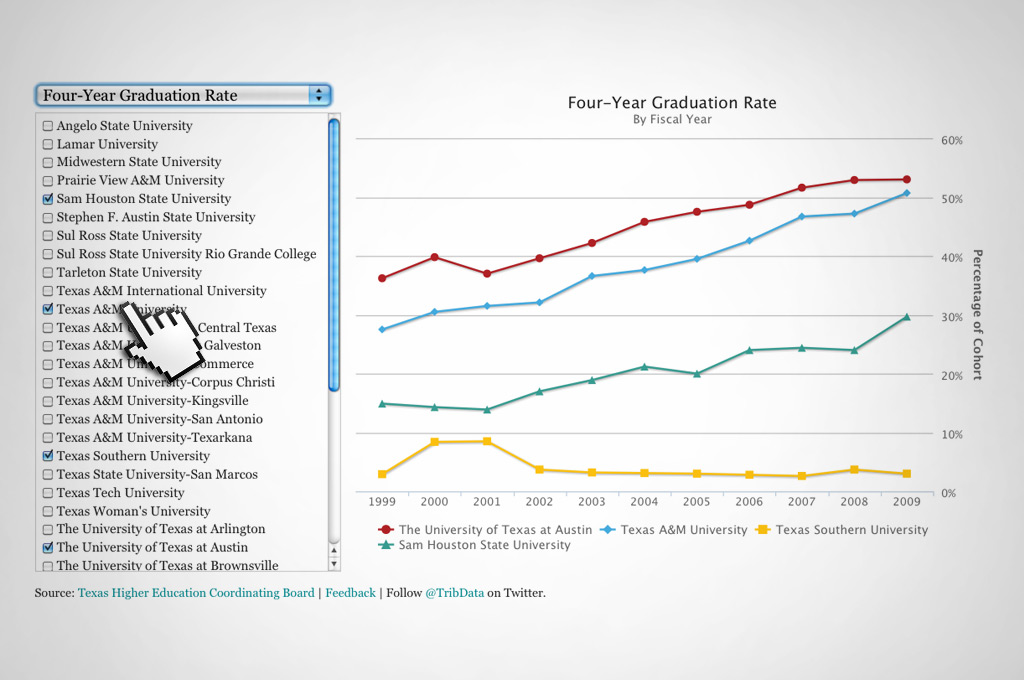

Only two of the state’s 38 public four-year universities can graduate half of their students within four years — and even then, just barely. At the University of Texas at Austin, the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board reports, 53 percent of incoming freshmen graduate in four years. Texas A&M University graduates 51 percent.

On the other end of the spectrum, rates are staggeringly low: Texas Southern University and the University of Houston-Downtown only graduate 3 percent of their students in four years, according to the same figures. The University of Texas at El Paso graduates 10 of every 100 students in that time frame.

Higher education and workforce development leaders throughout the state acknowledge and decry these dismal statistics, and many public universities are launching initiatives designed to improve college completion.

“We’re not getting the return on investment that we’re making” in higher education, said Bill Hammond, the president of the Texas Association of Business, which advocates for education reform in Texas. Over the next biennium, that investment will total about $21.8 billion.

But several Texas university officials question the graduation rate metric’s ability to accurately depict efforts to educate their increasingly nontraditional student populations. UT-El Paso President Diana Natalicio said while her university has a lot of work to do to get more students to graduate, those rates should not be used as the primary measurement of any university’s success.

“If we stick to graduation rates, public universities are always going to look less successful than private and elite institutions, because the surest way to assure high graduation rates is to increase selectivity,” she said.

For every 100 Texas high school graduates who pursued higher education at a public Texas institution in 2002, 21 started at a four-year university. Only five of those students had college degrees within four years. By 2010, four years later, eight more students had graduated, for a total of 13 university graduates in eight years. That’s the bleak picture painted by Complete College America, a nonprofit focused on boosting higher-education success around the country.

Bad as that may seem, the state’s completion crisis is far from the nation’s worst; data compiled by the coordinating board ranks Texas’ 49-percent six-year graduation rate 17th in the nation. But if — as Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce predicts — more than 60 percent of the country’s jobs in 2020 will require a higher-education credential, and only about 31 percent of Texas adults have at least an associate’s degree, there’s significant ground to be made up.

"It is an incredibly complex issue, and it’s very easy to generalize about the problem and about the solution," said state Sen. Judith Zaffirini, D-Laredo, the chairwoman of the Senate Higher Education Committee. "I think there are some wrongful, low expectations of students who could meet higher expectations. On the other hand, I don’t think all students should be subject to the same expectations."

The growing focus on graduation rates in Texas represents a shift from the access-oriented mind-set that dominated the state’s higher-education approach for the last decade, a push that introduced record numbers of students into the higher-ed pipeline.

Widely viewed as a positive development, the increased access has brought new challenges, including a larger population of nontraditional students who have to work, need additional advising and attend universities part time.

Texas Higher Education Commissioner Raymund Paredes believes the chief concern is a disjuncture between the K-12 system and higher education, with more students showing up unprepared for collegiate work. Having to sit through remedial courses dramatically decreases the likelihood of graduation.

State Rep. Dan Branch, R-Dallas, the chairman of the House Higher Education Committee, said that in addition to the challenges with nontraditional students, there is a retention issue. “There’s not enough advising, not enough help with course navigation, not enough orientation where people feel connected,” he said. “There’s not enough intervention programs, or the online tools aren’t available.”

As officials examine why higher-education graduation rates are floundering, reform advocates suggest that altering the funding formula may provide an incentive for major change. Hammond of the Texas Association of Business and other advocates have called for the Legislature to tie a chunk of state appropriations to metrics like graduation rates rather than the current model, which is solely focused on — and rewards increases in — enrollment. They want to focus on improving graduation rates rather than quibbling over how to measure them, observing that the rates are low no matter who runs the numbers.

“If they want to say a number’s off by 10 percent, so what?" Hammond said. "Let’s stop arguing about a few percentage points and turn our focus on completions."

Although a shift to some form of outcome-based funding is widely seen as an inevitability in Texas higher-education circles, it is also clear that it will not be tied to graduation rates. An uneasiness about graduation rates permeates much of higher education.

“There’s a lot of confusion about what it includes and what it doesn’t include and how it’s measured,” said coordinating board spokesman Dominic Chavez.

For example, many Texans might be surprised to learn that the six-year graduation rate — not the four-year rate — is the industry standard, a nod to the increasing amount of time students are taking to graduate.

| School | Grad Rate |

|---|---|

| The University of Texas at Austin | 53.0% |

| Texas A&M University | 50.7% |

| The University of Texas at Dallas | 42.0% |

| Texas Tech University | 40.4% |

| Texas State University-San Marcos | 30.1% |

| Sam Houston State University | 29.7% |

| Texas A&M University at Galveston | 26.9% |

| Stephen F. Austin State University | 25.6% |

| The University of Texas at Tyler | 24.8% |

| University of North Texas | 24.3% |

| Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi | 23.5% |

| West Texas A&M University | 23.2% |

| Angelo State University | 22.4% |

| Texas A&M International University | 21.3% |

| Texas Woman's University | 20.7% |

| Tarleton State University | 20.6% |

| Texas A&M University-Commerce | 20.6% |

| The University of Texas of the Permian Basin | 19.5% |

| The University of Texas at Arlington | 19.1% |

| The University of Texas-Pan American | 18.3% |

| University of Houston | 17.0% |

| Texas A&M University-Kingsville | 15.5% |

| Midwestern State University | 14.3% |

| Prairie View A&M University | 11.5% |

| Sul Ross State University | 11.2% |

| Lamar University | 10.6% |

| The University of Texas at San Antonio | 10.3% |

| The University of Texas at El Paso | 10.0% |

| Texas Southern University | 3.0% |

| University of Houston-Downtown | 3.0% |

| Sul Ross State University Rio Grande College | Not rated |

| Texas A&M University - Central Texas | Not rated |

| Texas A&M University-San Antonio | Not rated |

| Texas A&M University-Texarkana | Not rated |

| University of Houston-Clear Lake | Not rated |

| University of Houston-Victoria | Not rated |

| University of North Texas at Dallas | Not rated |

| The University of Texas at Brownsville | Not rated |

The only way to compare graduation rates from state to state is to rely on the federal Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS), which makes Texas’ numbers look even worse. According to the federal system — originally crafted to track college athletes — only five Texas public universities have a six-year graduation rate of at least 50 percent, whereas the coordinating board’s system shows 13 institutions crossing that threshold.

Paredes recently said IPEDS “provides a distorted and uneven view” of graduation rates because it only measures the number of first-time students who enroll full time as freshmen and finish at the same institution where they began. Texas students, especially those at institutions other than UT and A&M, are prone to move around. At UTEP, for example, this approach to measuring graduation rates excludes roughly 70 percent of the students enrolled.

Chavez said the state’s system can track students more closely and account for them as they transfer and move in and out of the system. “The only thing we don’t have visibility on is when the student leaves the state of Texas,” he said. To provide a more comprehensive portrait of the state’s situation, the coordinating board intends to publish graduation rates for part-time students starting this spring.

Zaffirini said improvements may be difficult without sufficient state support for financial aid, which has recently been on the decline. "Like it or not, some legislators are going to have to realize that it’s tied into funding in many ways, not all, but many ways," she said.

Spurred in part by the state’s strained economic situation, higher ed officials are taking a close look at the value of underperforming programs. Last year, the coordinating board began cracking down on majors and minors at universities throughout the state, shuttering hundreds that failed to graduate an average of five students per year over five years.

The thinking, Chavez said, was “if we’re not graduating enough students in it, are we really accomplishing anything?” He said there has been no discussion of expanding that mentality beyond specific degrees to entire underperforming campuses.

Given the state’s budget crunch, universities will have to boost their efforts to improve graduation rates without new state resources. But there is evidence that public universities are working on it. At Texas Southern, a historically black university in Houston, President John Rudley has tightened admissions standards in an effort to bring the school’s graduation rate up. He said the key to understanding why the rates are so low lies in appreciating each institution’s unique origins. “It’s not that we’re one-size-fits-all,” he said. “We don’t all have the same resources. We don’t all have the same history. We don’t all have the same support from the state.”

The pressure to improve extends to all institutions, not just those with the worst graduation rates. UT-Austin, which has the state’s highest four-year graduation rate, announced an initiative to bring its rate up to 70 percent by 2016. That means the nearly 20-percentage-point leap will have to be made by the freshman entering this fall.

A UT-Austin task force recently issued 60 recommendations for academic improvements, including better intervention programs for struggling students and measures to make it difficult to alter one’s degree plan as graduation draws close — and to remain in school once the necessary credits for graduation have been acquired.

And institutions around the state are attempting to heighten their responsiveness to the growing needs of students, especially those who don’t have parents or mentors with degrees, by putting a renewed emphasis on academic advising. Sam Houston State University’s student advising and mentoring center has received national recognition.

Branch, the House Higher Education Committee chairman, sees progress. “Given being a border state with a large minority population, being 17th in the nation is probably better than a lot of people think of us,” he said.

Still, he said, the state’s numbers are unacceptable. “I’ve talked to a lot of presidents who will acknowledge their embarrassment about their graduation rates,” he said.

This is the first installment of a four-part series on the completion crisis at public universities in Texas. Part Two is about how the University of Texas at El Paso aims to redefine success. Part Three discusses Texas Southern University’s attempts to rise from the bottom of the state rankings. And Part Four covers how Sam Houston State University credits its advising center for a rise in graduation rates.

The Texas Association of Business is a corporate sponsor of The Texas Tribune.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Reeve_1.jpg)