Saving a College With Persistence and Prose

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/TxTrib-PaulQuinn006.JPG)

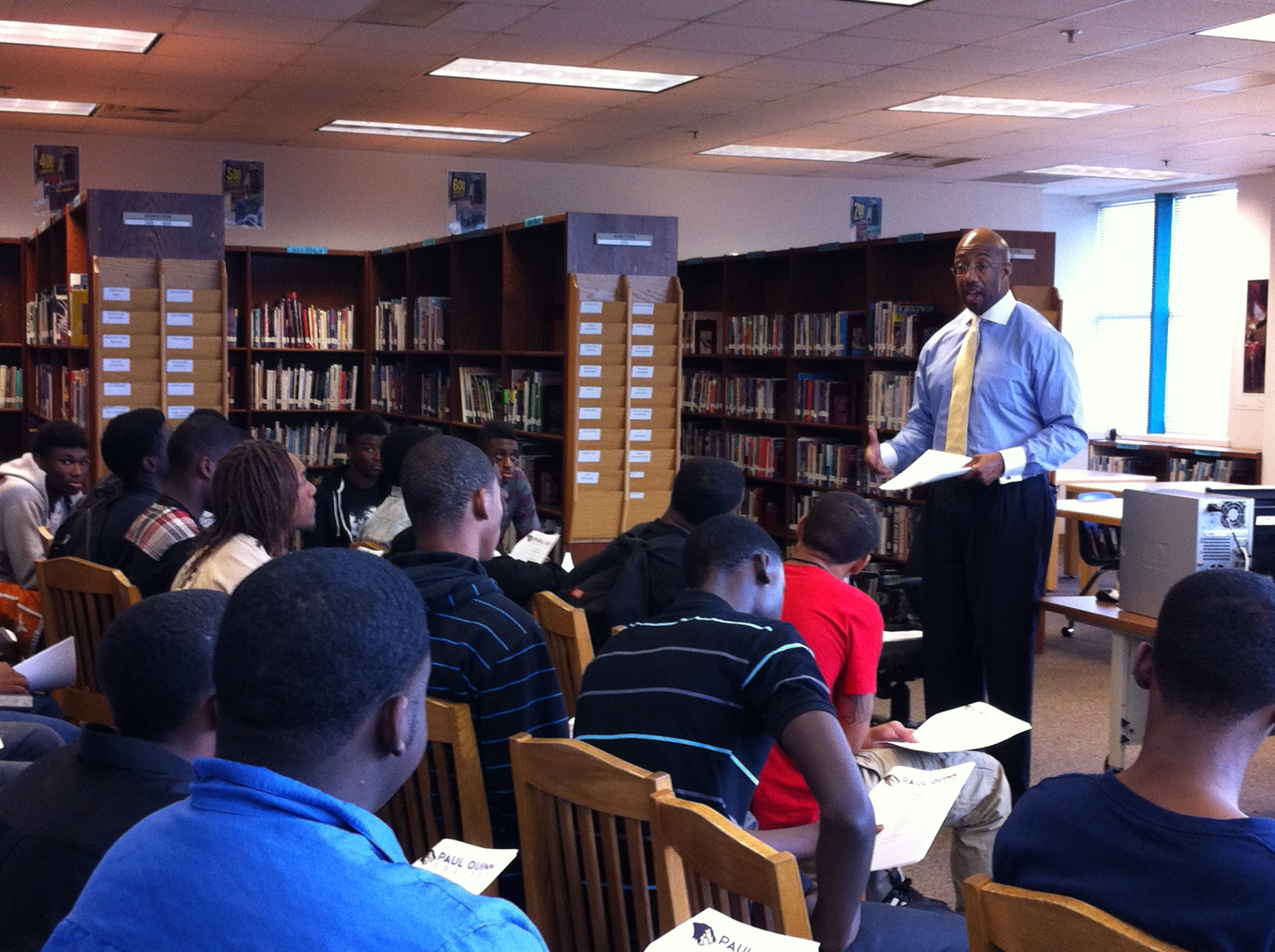

DALLAS — At 11:11 a.m. on Nov. 11, in the Moisés E. Molina High School library, the handful of boys that make up nearly the entire black male population in the nearly 1,900-student school sat listening to Michael Sorrell.

Sorrell, the energetic president of nearby Paul Quinn College, a private, religiously affiliated, historically black institution, was reading poetry for 11 minutes. “If you’re going to do this job, you have to inspire people,” he said later that day.

When Sorrell was growing up, the elders in his family sent him “If,” by Rudyard Kipling, every year on his birthday. This day happened to be his 45th. So he began, “If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming it on you / If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you, but make allowance for their doubting too . . . ”

Sorrell is no stranger to maintaining faith despite the odds. In 2007, he assumed his current position during one of the rockiest patches in the college’s now 139-year history. Paul Quinn College may not be out of the woods yet, but through a combination of vision, bullheadedness, and the kind of charisma that begets donations and good will (Sorrell is also a Texas bundler for President Obama), he has steered the college from the brink of closing to its new perch as an emerging national and community leader.

The 146-acre campus is an oasis in the low-income Highland Hills community. Thirteen abandoned buildings were removed from grounds in 2010, one of many changes under Sorrell’s leadership. Others include putting admissions standards in effect, eliminating the football team, cleaning up the finances, enforcing a new dress code, and bringing in an almost entirely new faculty and staff.

Paul Quinn is also one of the community’s only sources of quality food; with PepsiCo’s help, the football field has been trans-formed into the Food for Good Farm at Paul Quinn College.

The farm has yet to attract healthy dining establishments or a grocery store as Sorrell had hoped — either of which would be the area’s first — but he said, “It told people there might be something going on down there.”

Still, there are setbacks. The latest is a plan to expand a nearby landfill. The City Council recently approved the proposal without conducting any impact studies. The Quinnites, as they call themselves, organized protests of the process, galvanizing the community with their “We Are Not Trash” campaign. Sorrell said he had intended to spend the fall focused on building a new kindergarten through 12th-grade school on campus.

On the ride back from Molina High School, he talked about the way he got his job.

“I know I wasn’t the first choice,” he said. “You have to get to the point where you say, ‘Hey, let’s pick the guy with no higher ed experience to hand our school that’s struggling in every way.’”

In fact, Sorrell had been angling for the position for several years, albeit not in the traditional manner. He had grown up in Chicago, the son of a restaurateur and a social worker, and he was the only college student in his family who did not attend one of the country’s historically black institutions.

After earning a bachelor’s from Oberlin College and master’s and law degrees from Duke University, Sorrell did not head for the halls of academia. He enjoyed professional success as a lawyer, he worked in the Clinton White House as a special assistant in the executive office of the president, and in 2004 he was a cofounder of a public affairs consulting firm. When he took the job at Paul Quinn — where he is known affectionately as Prez — he took a significant pay cut.

He got to know about Paul Quinn after befriending a group of alumni when he moved to Dallas in 1994. “People hated their school,” he said. “They just dogged it.”

But when the Paul Quinn president left in 2001, Sorrell felt compelled to change that. He called the headhunters and told them he would like the position, but he could not even get an interview. He worked his way onto the board — “the consolation prize,” he called it. After brief stints by two other presidents, he got another shot.

In 2009, just two years into his job, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools announced that it was stripping Paul Quinn of its accreditation, a requirement for state and federal aid. But the college was able to get an injunction from the court and has maintained accreditation on probationary status.

The news precipitated a slew of negative news media coverage and an exodus of students. Enrollment, which had been more than 550 in 2007, dropped to a low of around 150. One morning, Sorrell said, “I cried in a way I haven’t cried since my mother died.”

But, he added, “One thing people should know about me: I don’t ever believe in losing.”

Now the school has roughly 200 students, and Sorrell’s goal is to expand that to 2,000 by 2020. It is bolstering its recruitment of Hispanic students, and it will soon start a soccer team. Taking transfer students into account, the six-year graduation rate at Paul Quinn has increased to 27 percent, from 6 percent when Sorrell took the job.

Sorrell said he would not be happy until it reached 90 percent. When it was pointed out that the rates at the state’s top universities are not that high, he said, “That’s not my problem.”

Audio: Paul Quinn student Celia Soto

Earlier this year, Paul Quinn received accreditation through the Transnational Association of Christian Colleges and Schools, securing students’ access to federal financial aid.

On the morning of Nov. 11, Sorrell had flown from Nashville, where he had received a leadership award at the TRACS annual conference. Earlier this year, HBCU Digest, which reports on historically black colleges and universities, presented Paul Quinn with the HBCU of the Year award.

"I always felt that I could make a difference,” he said. “What I didn’t know was that this turns out to be my calling.”

That does not mean closing the door on his dream of owning an N.B.A. franchise or running for political office. Sorrell said, “I assume that at some point in my life there will be public service, but I’m not sure this isn’t it.”

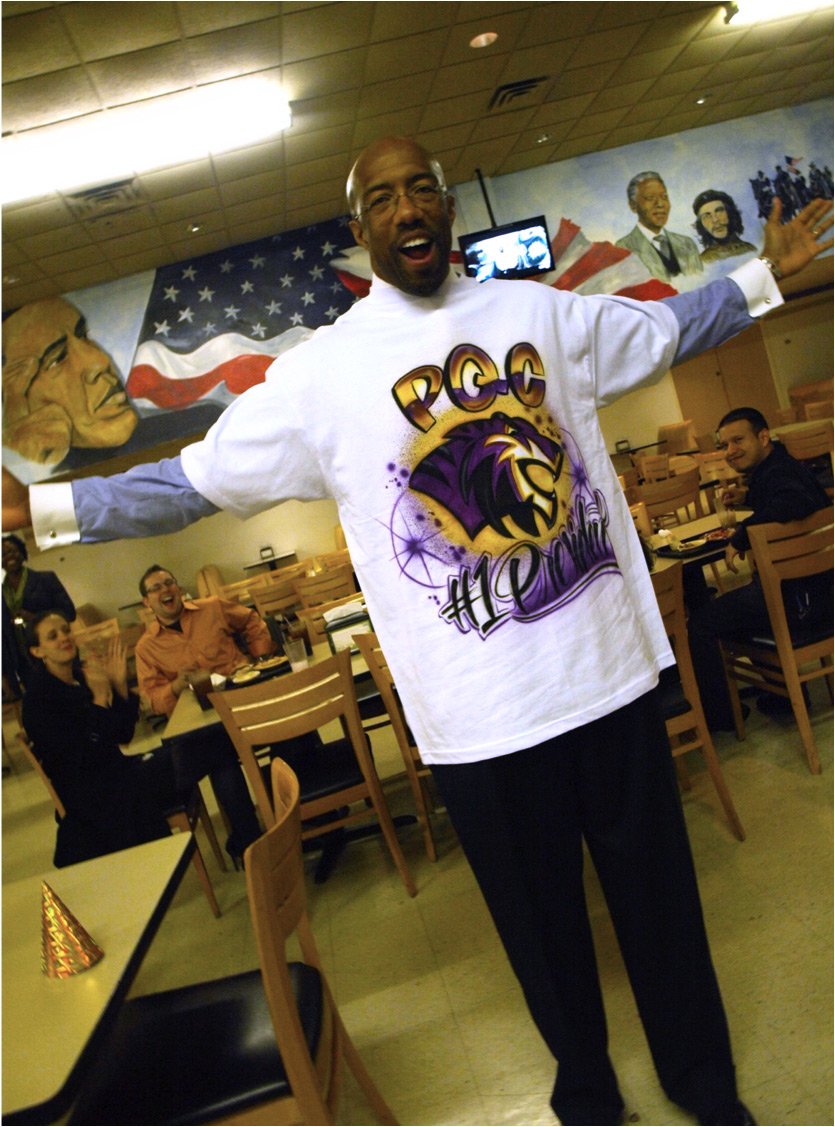

When he returned from Molina High School, a surprise party awaited him in the Paul Quinn cafeteria. Students, faculty members and staff passed around a microphone and, in some cases literally, sang his praises.

At one point, the microphone stopped with Ronisha Isham, a sophomore. Sorrell has developed a personalized approach for supporting Isham, just as he has for many students. Each week she must memorize a poem and discuss it with him. (While the recitation is difficult, it is most likely preferable to Sorrell’s method with one young man, who must pick up garbage “because he made garbage man grades last semester.”)

Isham offered to recite the previous week’s assignment — “If,” by Rudyard Kipling. Her fellow Quinnites cheered her on, until she reached the end: “Yours is the earth and everything that’s in it, and — which is more — you’ll be a man, my son!”

Later that afternoon, she was in Sorrell’s office reciting her latest, “To an Athlete Dying Young,” by A. E. Housman. She got through it but expressed doubts about doing another the following week. Prez insisted.

“Thank you,” she said. “I don’t know why you’re doing this, but I know I will someday.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Reeve_1.jpg)