A Matter of Degrees

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/020210_stoppingshort.png)

As it recruits students, Austin Community College makes pitches similar to those of two-year schools statewide, which now educate more than half of Texas collegians. ACC’s slogan — “Start here. Get there.” — implores students to take advantage of its inexpensive and flexible course offerings before moving on to get their university degree.

“Texas community colleges enroll 54 percent of the state's college students, 75 percent of freshmen and sophomores, and 78 percent of all Texas minority students,” the school's website reads. “ACC transfer students excel, doing as well as or better than students who begin at a four-year university.”

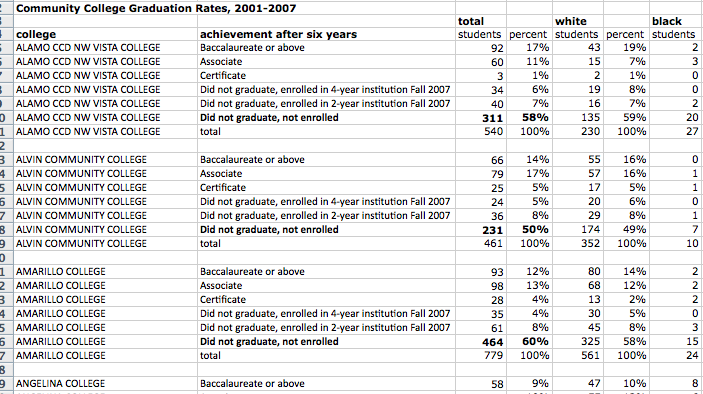

Absent from that portrait are graduation rates that paint a bleak picture of community college achievement at ACC and statewide: Most students who start there, in fact, get nowhere, at least in terms of a degree or professional certificate. The majority of students don’t transfer at all, and only 15 percent who start community college full-time go on to earn four-year degrees within six years, according to the latest available state data tracking full-time students over the long-term. Even fewer earn two-year degrees from two-year colleges: just 11 percent statewide. An additional 5 percent earned professional certificates in vocations that range from nursing to welding.

So all told, just three out of 10 full-time community college students end up with any credential after six years. And that figure doesn't include tens of thousands of part-time students — the majority at many campuses — who experts say are even less likely to finish.

A separate set of federal data, gathered by the U.S. Education Department, tracks students seeking two-year associate degrees between 2004 and 2007. Just 18 percent earned the credential within three years, compared to 28 percent nationally. Texas ranked 42nd in the nation and behind every state in the south and west except South Carolina.

Officials at ACC and other community colleges argue such statistics don’t paint the full picture of success on campuses that by their nature have difficult and diverse missions in educating often ill-prepared students. They note, for instance, that some students earn enough credits in community college to get a two-year degree — but never file the paperwork to receive it, believing that they will get a four-year degree later. They say the statistics, the only completion data tracked by the state’s Higher Education Coordinating Board, do not account for the majority of community college students, who enroll in less than a full load of classes.

Community colleges for years prided themselves on providing access for higher education for lower income and minority students previously shut out of universities. Many colleges across the state, including ACC, only in recent years have started taking a hard look at all kinds of data on credential completion, says Kay McClenney, director of the Center for Community College Student Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin. That effort has mostly been voluntarily. What’s needed now, McClenney says, are rigorous standards imposed systematically statewide, McClenney said.

“One of the reasons graduation rates are as low as they are is because it’s never mattered. There’s been no funding policy, no accountability policy, no policy whatsoever that has made it matter,” McClenney says. “You hear people say, ‘The community college mission is different and complicated.’ And it is. They say, ‘People don’t always come here to graduate.’ And that’s true. But it’s the truth we hide behind that keeps us from getting serious about improving graduation rates.”

ACC is by no means a low-performing community college when compared to other Texas community colleges. Its completion rates by full-time students are roughly in line with state averages. Kathleen Christensen, ACC's vice president of student support and success systems, points to another set of historical data showing that the system has over the last decade boosted the number of associate degrees and certificates awarded annually from 1,100 to more than 2,600 (though enrollment increased markedly during that period, as well.)

“I say that if you look at all the parameters and all the caveats of who the students are, and what their goals are, that we’re doing OK,” Christensen says of the state graduation rate data. “But we need to improve, and we are improving.”

Starting behind, quitting early

McClenney and other higher education experts say that community college leaders should be glad that the state figures, which followed the class of 2001 through 2007, only include full-time students — because including all others would likely make the graduation statistics even lower. “What you see here is a political victory by the college presidents that allows them not to count large numbers of students that come to them,” McClenney says.

Looking only at full-time students, often among the most prepared and likely to succeed, excludes the majority of students who start community college by taking “developmental education” courses (remedial classes designed for students who didn’t get the basics in high school) or who took extended breaks between high school and college. And part-time students generally are less likely to earn credentials.

“The rates would go way down,” says Temple College President Glenda Barron, who took the helm of that school in 2008 after 20 years at the coordinating board, most recently as an associate commissioner. “We have so many students who need those developmental courses, and most are not in the statistics.”

Community college officials concede that many of the students they lose start their college careers with serious deficits and quit early. Of more than 95,000 first-time-in-college students at community colleges, just 34,000 met college-ready standards in math, reading and writing. The rest were required by state law to pass at least one developmental education course — for no college credit — as a condition of enrollment. Those remedial requirements can be a debilitating setback. All entering students must take tests required by the Texas Success Initiative, meant to gauge their fitness for freshman-level work. Those who score at the lowest level in a particular subject may be required to pass up to three semester classes before moving on to college-level work. “The colleges are using the developmental courses as the technique for getting them in,” Barron said. “And we lose a lot of those students because they think, ‘I’m not making any progress, I’m not even taking college credit math yet.’”

At El Paso Community College, where state data reports less than 20 percent of full-time students earned credentials, the student enrollment is overwhelmingly Hispanic and low-income, and about 90 percent of students are required to take developmental math. President Richard Rhodes is betting that many of those students don’t need a full semester course or more to catch up. Often, students don’t come directly from high school and may test poorly but only need limited review to catch up. So in addition to installing a new math program, Rhodes has instituted a new policy allowing students to retest at any time, letting them leap forward when they’re ready. “Often times, there’s a lot of finger-pointing, people saying it’s either our fault or the public schools’ fault that they can’t pass the [placement] test,” Rhodes says. “I think we’re all trying to find the right answer. We’re focusing on developmental education.”

The developmental education practices statewide are in need of a major overhaul, says Commissioner of Higher Education Raymund Paredes. Because community colleges are open-enrollment, meaning they have no admissions standards, they end up taking many students who simply are not prepared to be there, Parades says. Developmental classes, at least as currently structured, usually accomplish little but separating students from a few credit hours worth of tuition money. “You have some students who come with a fifth grade reading level, not remotely capable of college writing,” Paredes says. “Students at such low levels should probably be in some kind of adult education classes before attempting college work.”

The proportion of developmental education students who go on to complete college credit courses — much less a degree — is “very small,” Parades says. “We’re spending an awful lot of money trying to help students that we ultimately don’t help.”

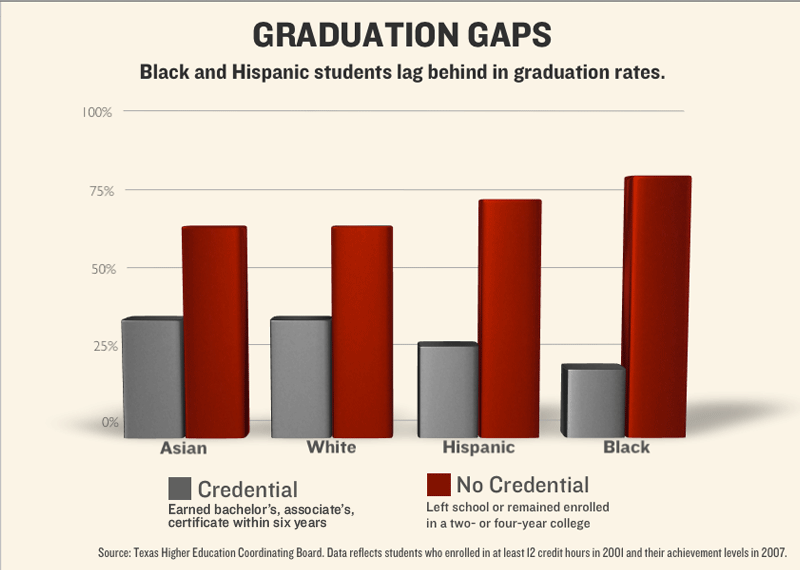

Graduation gaps

As low as the graduation rates are for all two-year college students in Texas, they mask an even bigger failure to ensure that minority students succeed. At El Centro College in the Dallas County Community College District, 160 African-American students enrolled for a full class load in 2001. Six years later, just 7 of those students had earned four-year degrees and 14 had earned two years degrees. A handful of others remained enrolled in either a two- or four-year school, while 129 students — 81 percent — dropped out with no credential.

Statewide, among full-time students, black students ended up dropping out with no credential in 68 percent of cases, compared with 59 percent for Hispanics, 53 percent for whites and 46 percent for Asians.

With minority and lower income populations growing quickly in Texas, such gaps should demand urgent attention from the higher education community and state policy makers, McClenney says. “That’s the future of the state looking at us,” she says.

At ACC, just 12 percent of full-time African-American students earned two- or four-year degrees within six years, according to the state. The school has started tracking that kind of data on its students — among a host of other student performance measures — and pushing it down to faculty members in specific departments, Christensen said. One outgrowth of that focus is the school’s “men of distinction” program that connects black students with black faculty and advisors.

“Each department elects a faculty coach to lead discussions: What are we doing here? And what are we doing to improve?” Christensen says. “One of the things we’re working on is retention of African-American males.”

Focus on results

When community college leaders talk about graduation rates, they often launch into anecdotes about this student or that who got no credential but benefitted nonetheless. Asked how much college achievement it takes before such benefits kick in, Rhodes, the El Paso College president, echoed others in saying, “Every bit of education adds value.”

That may be true ethereally, but not economically. The leading study of how much college it takes to actually improve quality of life came in 2005 from Community and Technical College Board of Washington State. Researchers tracked some 35,000 students of various ages, education levels and background from the community college door into the work force. Their findings: It takes at least a year of school — and a credential — to make any real difference in earning power. Otherwise, the benefits were “negligible,” the study found.

“I’m really skeptical of institutions saying somebody takes a class and it adds value,” says Michael Collins, program director for the Boston-based nonprofit Jobs for the Future and a former associate commissioner of higher education in Texas. “As we transition to a more knowledge-based economy, some form of higher education has replaced high school as the floor. The days of making an excellent living with a high school diploma are really gone.”

In hopes of focusing community colleges less on access to higher education and more on results, a host of nonprofit education organizations nationally have banded together in an initiative called Achieving the Dream, backed by $100 million in philanthropic funds; Houston Endowment is among its financiers. The 102 colleges who have signed on nationwide include 20 from Texas, including ACC. In all, they serve two-thirds of total enrollment in community colleges, McClenney says.

Among the project’s requirements: a “rigorous, hard-nosed approach” to tracking achievement and completion data on every student, full- or part-time, she says, and a major focus on developmental education. “The most significant thing is to invest in developmental education, unapologetically and with high expectations” for the masses of students who exit high school unprepared for college, McClenney says. “We can wish that wasn’t true, we cry and whine about it, but it’s not going to change it.”

Editor's note: This story was changed to correct the spelling of Kay McClenney's name.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/tt_bio_thevenot_brian.jpg)