Texas removed six Black children from their homes. Their adoptive parents drove them off a cliff.

Roxanna Asgarian, who covers law and courts for The Texas Tribune, is the author of “We Were Once a Family: A Story of Love, Death, and Child Removal in America,” published today by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, from which this essay is excerpted.

On April 13, Asgarian will talk about her book at a Texas Tribune event. Register for the event here.

Editor’s note: This story contains explicit language.

People came to this place for its sweeping views. The circular gravel turnoff sat alongside the Pacific Coast Highway, just across a small bridge over the tiny Juan Creek in Mendocino County. From its edge you could see the rocky Northern California coastline, its cliffs dotted with native grasses and wild succulents. At low tide, you could see the beach where fishermen used to camp, casting their wide nets to catch the night fish that flung themselves onto the waves during spawning season. On March 26, 2018, a clear blue day, a German tourist stood at this spot, but something alarming marred her view: At the bottom of the steep and jagged cliff, she spotted an SUV flipped on its hood, crumpled, its undercarriage exposed.

Cops called to the scene found Jennifer and Sarah Hart, a married couple, strapped inside, dead. Three bodies of children were scattered near the car, having been ejected from the vehicle in its plunge. At first, emergency response teams thought it might have been an accident. After police officers found identification for the two women in a backpack that had been in the car, they realized there were likely more bodies to be found: The couple, two white women, both 38, had adopted six Black children, ages 12 to 19, from two separate sibling groups, all from Texas. Search teams later found another of the children’s bodies, and a foot inside of a shoe that was believed to belong to another of the children. One child, 15-year-old Devonte, was never found. As firefighters towed the Yukon up the treacherous incline to the overlook where the SUV had gone over the edge, state troopers working the crime scene found no skid marks where the car had left the road.

Jennifer spent her days posting photos to Facebook of the kids adventuring on road trips, meditating in the woods, and at home playing with chickens. But shortly after the SUV was found, news stories started tumbling out that shattered Jennifer’s painstakingly crafted image. Investigators at the scene of the crash determined the car had actually accelerated off of the cliff. It emerged that the crash was intentional, and the kids had been drugged with Benadryl. Child Protective Services in Washington State had been trying to reach the family in the days leading up to the crash; the Harts’ next door neighbors in Woodland, Washington, told reporters that they’d finally called CPS after Devonte had snuck over multiple times late at night asking for food.

It turned out that the Harts, who had lived in Minnesota, Oregon and Washington State during their decade with the children, had been investigated for potential abuse and neglect in each of those states. The children were much too small for their ages — child welfare officials in Oregon pointed out in their investigation that five of the six children were not even on the growth charts for their ages. Still, the children remained with the women, who seemed to move around whenever suspicions became too intense.

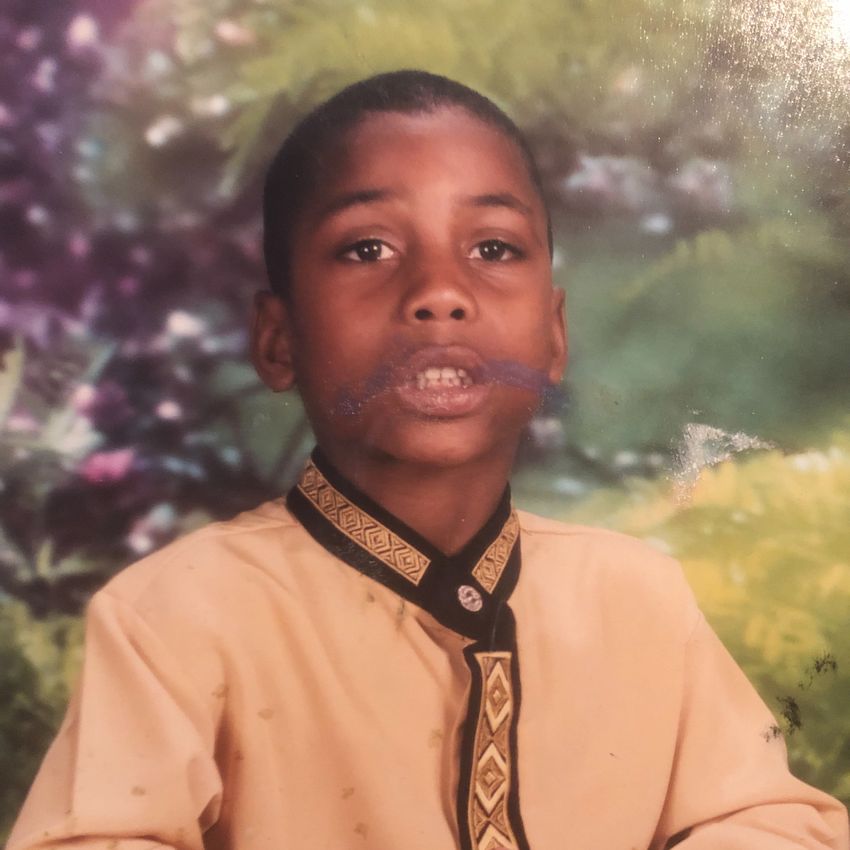

Three of the Hart children — Devonte, Jeremiah and Ciera — were born in Houston, to the same mother. They were removed from their family, including an older brother, Dontay, who stayed behind in foster care for most of his childhood. In the media frenzy over the Hart family tragedy, their story got largely overlooked, along with the story of their adoptive siblings — Markis, Hannah and Abigail, whose mother grew up around Corpus Christi. While many of the big stories focused on the white women’s intentions, psychological motivations and personal histories, stories about the Black children — who they were, where they came from, what happened to their birth families — were mostly absent. For the past five years, I’ve been working to uncover those stories.

It was a mild day in Houston, and Dontay Davis had started a fight at school again. His cousin Boogie found him in the halls of the Gregory-Lincoln Education Center, the Fourth Ward school both boys attended. It was December 2006 and Dontay was in fifth grade. Boogie was a couple of years older, but he’d flunked a grade and so was just one year ahead.

Dontay had always been a fighter. Sometimes fights started when a kid would say something to him he didn’t like, but other times he’d pick them himself. He wanted to show the others in his school that he wasn’t a punk, and he told himself that’s why he did it, but really, deep down, he liked the way it felt to exchange punches, even when he lost. It released something in him he was always carrying; for a moment, he felt clear and light. The fight that day, he remembers, had been with another boy over a girl in class. So when Dontay met up with Boogie in the hallways at school, he expected his cousin to talk about that. Instead, Boogie asked him if he knew what was going on at his house.

The lightness vanished and a pit landed in Dontay’s stomach as he heard the words come out of his cousin’s mouth. Before Boogie had even told him what was happening, he knew that it was Child Protective Services, and he knew he was going to have to leave.

During class later, Dontay got called to the office. His CPS caseworker, Tamika Lipsey, was waiting for him. He asked her point-blank if she was going to take him away.

“Why do you always ask me that?” she said.

He didn’t trust her, because he knew what happened when the caseworker showed up. “Every time I see you, you take me away,” he told her.

Tamika assured him that she was only there to visit with him and make sure he was okay. He relaxed a bit, but she still asked him the same questions she always asked, questions he felt uncomfortable answering because he was always afraid of saying the wrong thing and he didn’t want to get his family in trouble. He knew what would happen if they got in trouble — he’d have to leave again, and maybe get split up from his brothers and baby sister again, and if he ended up back at the shelter he’d have to fight the big kids again to prove to the others that they shouldn’t fuck with him, and those kids were not like the kids at Gregory-Lincoln. They were meaner, and they were bigger. And worse, he knew he wouldn’t be able to see his mom, Sherry, anymore, and the family had only just got back to some sort of normal.

Tamika asked him how he liked living at his aunt’s house, where he’d been staying for close to six months. He told her he liked it — he got to play with his brothers Devonte and Jeremiah, with his cousins in the Fourth Ward neighborhood where his mother grew up, and on the computer at his aunt’s house. She asked him if there was anything he didn’t like, and he was careful to say no. She asked him what happened when he got in trouble. He told her he got spankings on his butt from his aunt; he hoped that was the right thing to say. He told his caseworker that on some weekends, they’d go back to Nathaniel Davis’s house, where they last lived before they were taken into foster care, and Nathaniel, whom Dontay referred to as his dad, would cook for them and they’d sleep over.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/bb7fafae7f1eba1f7018ebcc125498f0/IMG_1932.JPG)

Tamika left Dontay there at school and went back to the CPS office. She didn’t tell him this, but she had been disconcerted by her visit earlier that day to the apartment where Dontay lived with his two younger brothers and baby sister. Before she had gone to see Dontay at his school, she’d gone to check in with his aunt Priscilla Celestine. Priscilla’s brother Clarence was the father of Dontay’s two youngest siblings, Jeremiah and Ciera, and he had asked her to take the children in when they were removed from their home.

Priscilla was a churchgoing woman, unlike her brother, who was in prison for drugs, and her brother’s girlfriend, Sherry, Dontay’s mom, who had a well-known cocaine problem that had caused her to lose her children. Priscilla worked as a receptionist at a hospital and kept her nose clean — Dontay had told his caseworker, when she asked if they went to church, “That’s the only place we ever go.”

But Priscilla had been struggling with the new family setup, which had formed abruptly months after the kids were taken away from their home. The children had been in foster care at separate placements before they moved in with her. She was growing to love the children, especially her brother’s two, who were the youngest. And she wanted to keep all the siblings together — but four more children in her home, when it used to be just her and her daughter and granddaughter, strained her patience at times.

More than that, it strained her resources. This was 2006, more than a decade before Texas’s Department of Family and Protective Services began issuing a monthly payment of $350 for each child who was placed with relatives. Foster parents had long been given monthly stipends on a sliding scale to care for children, with high-needs children drawing the most money. But kinship placements, in which children were placed with relatives, didn’t qualify for those payments; instead, caregivers received a one-time $1,000 payment for the first child and $495 for each sibling, along with $500 a year for approved expenses.

For Priscilla’s family of seven, it just wasn’t enough, between new beds for the four children, increased grocery bills, clothes and shoes, school supplies, and diapers. The financial strain was exacerbated by the fact that Priscilla, whose two-bedroom apartment did not pass a home inspection because it was too small to accommodate the entire family, had needed to upgrade to a larger, four-bedroom unit in order for the children to be able to stay with her for the long term. She needed her full-time job more than ever, but there was also the matter of finding people to care for the children when she was at work. Dontay, ten years old, was in school, but the younger ones weren’t — Devonte was four, Jeremiah was two, and Ciera had just turned a year old when they moved in. She enlisted her daughter as the chief caretaker when she was away, but sometimes her daughter was busy. And Dontay’s school had been repeatedly calling her to come in, since he was always picking fights and getting into trouble. She needed to keep her job to have a chance in hell of paying for the kids, but she wasn’t sure she would be able to handle the new situation without help.

She’d regularly send the kids to their father figure, Nathaniel Davis — he wasn’t the biological dad of any of the kids, but he had given his last name to all of them. Nathaniel was the much-older partner of Sherry, the kids’ mom. They’d been together for a long time, and even though she was in and out of relationships with other men, he thought of her as his wife and thought of her children as his own. In fact, he’d been the primary parent caring for them since they were born. When Priscilla called, Nathaniel was over the moon to help. He had missed his children terribly since they’d been taken from his home the year before, after Sherry failed a drug test for the second time upon the birth of Ciera. He was hopeful that one day, after all the drama had quieted down, the kids would return to live with him.

And that wasn’t the only support Priscilla had. Sherry was keen to stay involved in her children’s lives. Priscilla had had to call and bother the caseworker multiple times about a clothing stipend for the children, who had badly needed winter clothes. But when Sherry came to visit she brought them the coolest new Nike sneakers and Polo shirts and Tommy Hilfiger jeans, even for the babies, as well as bags full of McDonald’s to fill the kids’ bellies. Sherry told Priscilla that if she ever needed her to watch the kids, she was only a call away. She missed her children, and although she wasn’t able to stay clean, she wanted nothing more than to be in their lives.

The problem was, Sherry had terminated her parental rights — her lawyer had said it was necessary to do so in order for Priscilla to be able to adopt them. This meant that she was no longer supposed to have contact with them at all. It was a condition of the children living with Priscilla that Sherry never be left alone with them. And Priscilla knew she shouldn’t risk it.

But there were times when there really were no better options. And one of those times was the very day Tamika Lipsey visited Dontay at Gregory-Lincoln and told him she wasn’t going to take him away. Before she went to Dontay’s school, Tamika had stopped by Priscilla’s apartment unannounced and found a strange woman in pajamas at the door. She said her name was Sherry, and that she was a “family friend.” Concerned, Tamika asked Sherry if she lived there. She said no, she just spent the night because Priscilla had to be at work early. The kids looked like they had just woken up, and when Tamika went to check their rooms she noticed none of them had any furniture. Sherry explained that the family had only moved into the apartment a couple of weeks before, and showed her which rooms were for which children.

Tamika called her supervisor once she’d arrived back at the office after checking on Dontay at school. Her supervisor told her to remove the kids, based on the potential risk of harm.

Sherry Davis was a Black woman from the Fourth Ward in Houston, Texas. Historically the center of Black life in Houston, the neighborhood was once known as the Mother Ward; before that, it was called Freedmen’s Town. It was where formerly enslaved people from the plantations along the Brazos River settled after news of the Confederacy’s defeat finally reached Galveston and the enslaved people in Texas came to know that they were free.

These newly freed people had settled on the marshy, flood-prone banks of Buffalo Bayou, along the same sludgy river that the brothers Augustus and John Allen had traversed in 1836 when they founded what would become Houston. At the time the freedmen settled the Fourth Ward in the late 1860s, the city didn’t exist much beyond downtown, and the banks of the bayou were considered undesirable property. It was here that the freedmen made and laid their own red- brick roads, carving symbols of hope on each one, and set to building homes and churches for the free Black families.

The Fourth Ward’s story is similar to that of many other freedmen’s towns around the country: In 1950, as cars became widely accessible, the government constructed an interstate highway, ramming it through the ward, and the community, cut in half, began to atrophy. Integration meant that well-to-do Black families, of which there were many in the Fourth Ward, began to settle in suburbs outside the city’s core. The Black community shrank, and those who remained were very poor. In the 1980s, crack cocaine took a firm hold. Then, after decades when the local real estate held barely any monetary value, the neighborhood, next door to downtown, suddenly became hot. Developers bought much of the land, sometimes by force, and renamed a good chunk of it Midtown, redefining its identity and erecting manicured retail centers filled with smoothie shops and chain pizzerias.

Sherry was born in 1970, by which time the Fourth Ward was already in decline. She and her younger siblings, Joshua and Alisia, lived with their mother in a white shotgun house with a gabled roof on the corner of Ruthven and Matthews, three blocks down from Mount Carmel Missionary Baptist Church. Sherry’s mother, Rose Mary Harlan, had herself grown up in the Fourth Ward.

When Sherry was a child, she witnessed her mother get shot and killed by her boyfriend. After that, her life was unstable; she dropped out of school, developed a cocaine addiction, and had and lost three children to the child welfare system.

By the time Dontay came along, Sherry was living with Nathaniel Davis. She’d known him for most of her life; he went by Joe Boy, and he grew up across the street from her mom and aunts back in the day. He was much older — when they reconnected, Sherry was 19 and Nathaniel was 47; he had been married and divorced, and had grown children. He was steady, though. The nature of their relationship was unusual: Nathaniel and Sherry had a partnership that would last decades, but she repeatedly had dalliances and sometimes serious relationships outside of their pairing. Nathaniel never fathered any of Sherry’s children. He did raise and nurture them all, though. He knew that he hadn’t done it right with his own kids the first time — he wasn’t around enough for them, and his one grown biological son wouldn’t talk to him because of it — and he wanted to do right by Sherry’s children. He wanted to be a good father.

When Dontay was born to a man Sherry was not in a serious relationship with, she gave the newborn Nathaniel’s last name, Davis, and the family left the Fourth Ward and settled down near Sunnyside. Sherry worked as a home health aide, leaving for several days at a time to stay in the home of the elderly patients she cared for, and she prided herself on not needing welfare checks to get by.

Dontay was five years old when Devonte was born, and Dontay loved being a big brother. Nathaniel would cook for the boys and clean up after them, and take Devonte to the hospital when his asthma got bad. By all accounts Sherry loved her kids—she kept her boys fed and clothed in fresh new sneakers. But she still had her cocaine habit. She’d get stressed and reach for her pack of cigarettes, slap them against her hand to pack them down, and sprinkle the white powder in the space left at the top. Lighting her primos, as she called them, made her feel good and helped her forget about the drama of the day.

Sherry took up with a new man, Clarence, but the kids stayed with Nathaniel, whom they considered their father.

Nathaniel told people he and Sherry were still together, and they were, in a way — whenever she came to stay, she cooked for her children and cleaned up around the house, and he raised the children when she was out. She’d stay out for days, sometimes for her job but other times for other reasons.

When Jeremiah was born in 2004, Sherry and the baby tested positive for cocaine, and Nathaniel got custody of the children, which really just solidified the relationship they already had in place. The boys got a bunk bed, and Jeremiah’s new crib was rolled in. Nathaniel’s grown daughter Carmenel came most days to help with the baby, and the boys slept in Nathaniel’s bed, all piled in together, while the new bunk bed sat empty in the boys’ room.

Dontay, Devonte, and baby Jeremiah were Nathaniel’s whole life, and he told the CPS caseworker that if he had to choose between Sherry and the children, he’d keep the kids in a heartbeat.

The situation was stable but still tenuous, with the threat of removal always hanging over the family. In 2005, Sherry gave birth to a baby girl she named Ciera. Sherry was still with Clarence Celestine, who was also Jeremiah’s father. In the hospital, Sherry again tested positive for cocaine, although the baby tested negative. She pleaded with the caseworkers, asking them to give her another chance. But her child welfare case was moved from the “reunification” track to the “termination” track, and the kids were taken from Nathaniel’s house, in part because he told them he didn’t know Sherry was using again. He had meant that she was never high around the kids, which is when he spent time with her, but they had seen his response as “enabling” her drug use.

The four kids were first sent to Nathaniel’s brother’s house, but after a caseworker stopped by and found the brother and his wife drunk, baby Ciera was sent to one foster family and the boys were moved to another. Eight-year-old Dontay lasted less than two weeks at the home, where he noticed there was a dog gate erected in the living room, separating the foster children from the foster parents’ biological children. The boys’ meals were strictly portioned, while the couple’s children got to eat what they liked. Dontay became enraged — he was old enough to understand they’d taken him from his family but not old enough to understand why.

The foster mother reported to his caseworker that when he would get angry, his eyes would roll back in his head and he would threaten his siblings and the other children in the home. The caseworker dropped him off at the CPS offices, and as she left, Dontay told her he was going to set her on fire for taking him there.

Dontay was sent to Intracare, one of Houston’s few psychiatric hospitals that accepted Medicaid patients. Intracare was at one time the second-largest psychiatric hospital in Harris County, before it was shut down in 2012 after the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services terminated its contract with the hospital for improper use of restraints and seclusion, a practice that posed a danger to patient health. Twice, the hospital was cited for chemically restraining patients without an updated treatment plan. Here, Dontay received a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder. Later, he’d be diagnosed with ADHD and bipolar disorder as well.

Dontay spent three weeks at Intracare in 2005, and he saw children there who were like him, children whose emotions were too much for them to handle. It was scary — there was the constant threat of a sedative shot, administered into the flesh of the butt, that would make you fall unconscious. He saw others get the shot, which they called “booty juice,” and he got it, too — more times than he could count.

But people were real in there, he thought. They didn’t pretend that everything was okay, that strangers were family, or that they cared and wanted to help. For the first time since he’d left his family, he felt like people were being honest.

Dontay bounced from the hospital to an emergency shelter to another foster placement before he finally got to reunite with his siblings at their aunt Priscilla’s house in the summer of 2006. That year, almost 348,000 children in Texas had been the subject of child welfare investigations, and 32,000 of those children were in the care of the state.

In 2004, the state comptroller, Carole Keeton Strayhorn, released a scathing report titled “Forgotten Children,” detailing high caseloads of up to 35 children per caseworker; this figure, more than double the recommended amount, resulted in nearly a quarter of the state’s caseworkers vacating their jobs each year. The report found that kids were often moved around from place to place and that some hadn’t seen their caseworker in months. It also showed photographic evidence of the squalor some foster children were living in, with some attending “therapeutic camps” where they had to use primitive outhouses and cook their own food outside, using meat patties that had been packed in coolers with no ice. “I challenge any defender of the status quo to put their child or grandchild in some of the places I’ve seen for one day, much less for a lifetime,” Keeton Strayhorn wrote in a statement issued after her report.

In 2005, the Texas legislature passed a reform bill that aimed to address some of the failures of its child welfare system by reorganizing the Department of Family and Protective Services. The bill would fully privatize its placement services and add $250 million to DFPS’s budget to hire 3,200 more caseworkers. But the move backfired, in a sense — from 2004 to 2006, the number of children removed from their homes increased from about 13,500 to about 17,500. The state had increased funding for CPS investigations but did not allocate additional funding for the foster placements — or for preventive services, like drug treatment and parenting classes, aimed at keeping kids in their homes. With placements at capacity, CPS acknowledged that children had been sleeping in their offices, with nowhere else to go. The privatization of placements was no remedy and had its own complications.

In 2006, when Dontay and his siblings were reunited at their aunt’s house, three children had died in foster care in different Fort Worth-area homes; they had all been placed by the same private agency, Mesa Family Services. The fallout stalled the state’s desired goal of putting its child welfare system, including both placement services and case management, fully in the hands of private providers. Instead, the agency was in limbo, responsible for more children than ever before but with a lack of quality placements to house them. Caseworkers were given far too many children to look after, and, because of that, the best interests of each individual child were subordinated to other concerns — such as the need to check all the boxes and stay out of the news for high-profile failures resulting in deaths of children.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/1a75fcf210488028a0998b22b695ec6f/IMG_3181.JPEG)

But Dontay didn’t know about any of this. All he knew was that when the caseworker came around, he was in danger of being taken from his family. It had happened before, and he had lived every day with a pit in his stomach, waiting for it to happen again.

That mild December day, his caseworker, Tamika Lipsey, assured him at school that she was just checking up on him, but when he walked up to his apartment after school, she was there again, in front of the apartment, putting his siblings into her car. His mom was standing out there, too, crying, begging Tamika to reconsider.

When Tamika had gotten the go-ahead from her supervisor, she’d driven back to the apartment from the office and found Sherry still there with the three youngest children. She ordered Sherry to dress them, and she told the children to kiss their mother. The children weren’t sure what was happening, but they knew their mom was upset, so they started to cry.

Unlike his siblings, Dontay understood in a split second what was going on. He began to cry, too, and hugged his mother. He told her he would be back; she said, “I hope.” She kissed him on the cheek and told him to look after his brothers and sister.

In the car, Dontay took Devonte’s face into his hands. The 4-year-old Devonte was quiet, observant — he always seemed to the rest of the family to be wiser than his years. Dontay told his brother, “I love you. This ain’t nothing . . . I’ll always be there.”

Because of his behavioral issues, Dontay ended up in one foster home; his siblings went to another. The pit in his stomach spread to his whole body. His biggest fear had come true, and he had a feeling deep down that this time the separation was for good. He knew his mom’s phone number, and as soon as he could, he snuck to the phone in his foster home without his foster mom seeing him. During that phone call, his mom promised him that she was doing everything she could to get them back. “Be calm,” she told him.

But Dontay wasn’t calm. He was sure he would never see his siblings again — and when he had strong feelings like that, he knew they would come true. It was nearly Christmas, and Dontay wanted to be home. He didn’t get to open all his presents from his aunt, and nobody knew him at the place he was staying. He tried his mother again on the phone, but she didn’t pick up.

Dontay, still just ten years old, took his belt, tightened it around his neck, and tied it to the bedpost. “I felt hopeless,” he says more than a decade later about that time in his life. “Ain’t nothing to live for.”

Priscilla Celestine tried hard to get the kids back. She filed for adoption, and when a judge denied her bid, she appealed the decision. Dontay was sent to live in one of the private residential treatment centers that house foster youth in Texas. In June 2008, Devonte, Jeremiah and Ciera were sent to live with Jennifer and Sarah Hart, a white lesbian couple in Minnesota, and by the next January, the three youngest Davis children were formally adopted by the Harts.

It wasn’t until July 15, 2010 — more than a year after the adoption was finalized — that Texas’s First District Court of Appeals affirmed the decision of the lower court against Priscilla, effectively closing the case and dashing her hopes.

A former Harris County judge in CPS cases, Michael Schneider, was not involved in the Davis children’s case, but he reviewed the case details years later. Schneider said that the children’s adoption should have been put on hold as Priscilla’s appeal went through the courts; if the appeal had been successful, the children’s adoption would have been void. “Somebody dropped the ball,” he said.

The family gave up, hoping that one day the children would get back in touch with them. Priscilla tucked away her grief, like she’d done many times throughout her life. “When they took them away, I prayed and thought it must be God’s will, and they must be in a better place,” Priscilla said, more than ten years later, inside her apartment at the same public housing complex where she had lived with the children. “I told myself that.”

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Roxanna_Asgarian_TT_01.jpg)