The inauguration of Greg Abbott and Dan Patrick cost millions. But much of it went to fundraising and staff.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/23e13cf85c9803010dafd704045b0bbd/Preparations%20Oath%20Ceremony%20MG%20TT%2006.jpg)

The inauguration of the Texas governor and lieutenant governor — traditionally two days of parties, picnics and parades — has been transformed into a giant payday for campaign staff and fundraisers.

The money spent on personnel, including payroll and fundraising, has skyrocketed during Gov. Greg Abbott's two swearing-in celebrations, dwarfing spending in those categories during the Rick Perry era, which spanned more than a decade, according to records obtained by The Texas Tribune.

The committee reported raising a record $5.3 million for inaugural events this year — $4.9 million of it from donors — and $1,860,624 of it was paid to inaugural committee salaries, “professional fees” and fundraising. That’s a six-fold increase from Perry’s last swearing-in ceremony, in 2011, when some $300,000 was spent on those categories.

Fundraising alone made up 19% of the amount raised from donors, or $931,000, and inaugural staffers received another $899,000. The categories were up 54% and 159%, respectively, from Abbott’s first inauguration in 2015 — which was the first year fundraising was listed as a line item, according to available inaugural records dating to 1979.

A Republican operative said spending that much of the total haul on fundraising fees “sounds exorbitant.” Another called it “absurd.”

“That is nuts!” the second operative said. “Egregious and wrong.”

Both requested anonymity for fear of professional repercussions.

The money for this year’s inaugural largely came from 219 contributions, 12 of which were for six-figure amounts. That would mean the committee spent more than $4,000 on fundraising for each contribution, which averaged $22,580.

One of the inaugural committee’s fundraisers was a team led by Abbott’s campaign finance director, Sarah Whitley. She referred questions to the governor’s spokesman, John Wittman, who said the fundraising figure appears correct but declined to comment on whether it was excessive.

Wittman could not say whether any of the money went to services like designing and printing materials — items that typically raise the cost of fundraising.

He has said no state dollars were spent on the festivities and that none of the $800,000 donated by the inaugural committee to charities — which he wouldn’t name — benefited entities tied to Abbott or the government.

Another inaugural fundraiser was a group called Fundraising Solutions, which lists Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick as a “current client” and describes high-profile Republicans like Rudy Giuliani, U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz and former presidential contender Bob Dole as “past successes” on its website.

The company did not respond to a request for comment, but its contact information appears at the bottom of a solicitation obtained by the Tribune that was sent to potential donors before the January inauguration. The company also features an image from the 2019 inaugural on its website and lists the event’s logo on its page of current clients.

A senior adviser for Patrick, Sherry Sylvester, said two of the lieutenant governor's campaign fundraisers were part of the inaugural fundraising team. They met their goal of raising $1 million, and each was paid $50,000, a 10% rate, she said. One Patrick staffer also worked with the inaugural committee and was paid $9,800 for two months of work, according to Sylvester, who declined to provide names.

It's unclear whether any other fundraisers received a cut of the $931,000. Wittman declined to comment on that point.

The executive director of the 2019 inaugural committee, Kim Snyder, who also serves as Abbott’s campaign director, did not respond to a request for comment.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/7cb185a2930067e0b8c1267914518292/15%20Greg%20Abbott%20Oath%20of%20Office%20Ceremony%20MG%20TT.jpg)

Like "shooting fish in a barrel"

Spending on each of the last two inaugurals eclipsed that of any other Texas inaugural for at least 40 years, even when adjusted for inflation. The closest contender is the inaugural featuring Democrat Ann Richards, but the spending on that 1991 event — $2.9 million in 2019 dollars, or $1.5 million at the time — is only half what Abbott and Patrick’s first inaugural cost.

The Texas inaugural’s fundraising costs also appear to be out of step nationwide.

Although the Trump inaugural committee came under fire for excessive administrative costs, it reported spending just $236,750 on fundraising for the 2017 events — and was able to raise $107 million. That would mean less than 1% of the haul was spent on fundraising.

In Florida, the inauguration for newly elected Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis also ran up a far smaller fundraising tab, according to an analysis of campaign finance reports. The Republican Party of Florida, which handles funding for the event, reported spending $184,500 on fundraising from the time the inaugural committee was announced through the swearing-in ceremony. The money could have been used for both the Republican Party and the inaugural, which cost about $3.5 million, according to media reports. The state GOP did not return a phone call seeking comment.

Rice University political scientist Mark Jones, who analyzed the Florida finance reports, said there is no reason to spend heavily on inaugural fundraising.

“It doesn't make any sense that a sitting governor of Texas who's going to be in office for four more years needs to do anything more than something purely administrative, that is: providing someone to receive the checks and cash the checks, and providing some type of online method for people to give donations,” Jones said. “A gubernatorial election ball sells itself.”

A former Republican officeholder in Texas similarly likened raising money for the inaugural to “shooting fish in a barrel.”

“It’s easy. You won,” said the former official, who also spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of professional repercussions.

Donations to the inauguration are not deemed political contributions under state statute — and corporations barred by state law from giving directly to Texas candidates have been among the biggest underwriters of the festivities.

Inaugural contributions differ from campaign giving in another respect: For both the Texas and presidential inaugurals, donors were offered a package of perks, including access to top officials and entree to special events.

“You really know what you're getting for [your contribution] with these big donor packages that are given out around inaugurations,” said Carrie Levine, a senior reporter for the Center for Public Integrity in Washington, D.C. who covered the Trump inaugural. “They're giving to a sure thing.”

Tribune has sued for records

Created by state statute, the inaugural committee is a unique and short-lived public entity. A 1998 letter from the attorney general’s office describes it as an “agency of the state of Texas,” but its powers are “relatively small” and “its object highly limited.”

The committee’s chairs are typically politically connected appointees, tapped by the governor and lieutenant governor to arrange two days’ worth of parties. State law requires that they maintain a record of their expenditures and file a brief financial report with the secretary of state’s office when the events are over. The committee can then be dissolved.

But where the spending records for the 2019 inaugural are now, and who has access to them, is not clear.

The Texas Legislative Council — a nonpartisan agency that assists lawmakers with bill drafting and other matters— provided the Tribune with invoices and checks that show the committee paid the council nearly $150,000 from a Frost Bank account for labor, a panoramic photo, supplies and coordinating the stage setup for the swearing-in ceremony.

The city of Austin, whose event center hosted the inaugural ball featuring country star George Strait, also received checks, which totaled $55,993. Invoices provided by the city bear Snyder’s signature and list her as the “bill-to” contact, along with her Abbott campaign email and a post office box used by the inaugural committee.

Most of the Tribune’s other requests for records have been futile.

Several state agencies pointed to the secretary of state’s office as the likely custodian of any records. But an employee there said this summer that the office has little expenditure information beyond a short financial report and that state law instructs the inaugural committee to maintain those records. When reporters visited the secretary of state’s office in person, a clerk said the financial report can only be obtained through a written request.

The Tribune also submitted public information requests to committee chairs. Snyder, the executive director, said in an email that they have “no responsive records.”

In mid-September, the Tribune asked the secretary of state’s office not to dissolve the state-created committee until the pending requests for information were fulfilled. But Secretary of State Ruth Hughs nevertheless abolished the committee Sept. 19, three days after the Tribune filed a lawsuit to obtain the records.

The office of Attorney General Ken Paxton, a prominent client of Fundraising Solutions, cites that order to dissolve the committee as its chief argument for why the Tribune’s lawsuit should be thrown out. A spokesperson for the attorney general's office did not respond to a request for comment.

Bill Aleshire, the Tribune’s lawyer, said, “The answer from the attorney general’s office misses the point. Regardless of whether the committee is dissolved, the records should have been retained or moved to the comptroller’s office or the state library, as required by law. The point of the lawsuit is to get the records disclosed, and we will continue to pursue all appropriate strategies for getting that done.”

Previous inaugural committees or organizers have turned over extensive records, though the quantity and format has varied over the decades.

In 2015, Abbott and Patrick’s first inaugural, a spreadsheet of wages given to inaugural staff was provided to the secretary of state’s office. Several Abbott staffers were among the committee employees who received some of the $1,389,551 spent on personnel, including salaries and fundraising, that year.

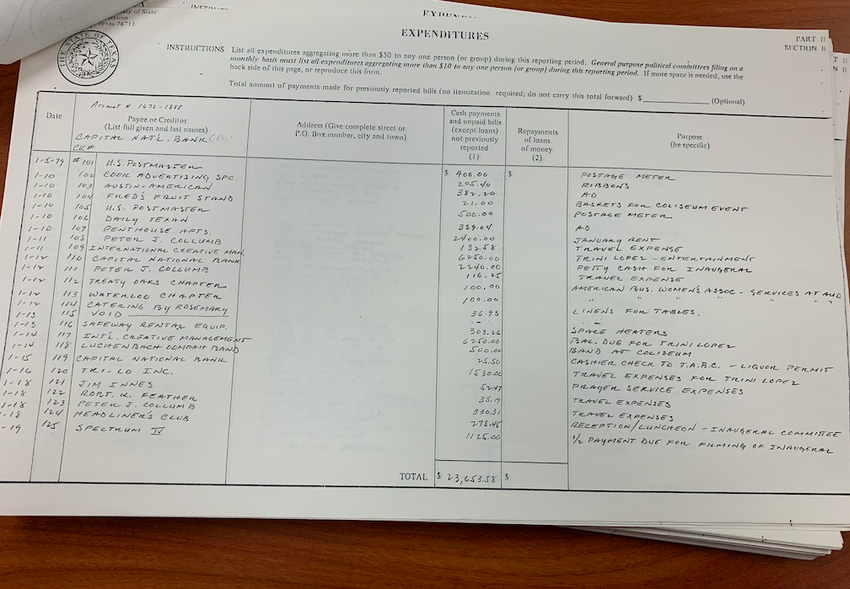

Past committees have also sent reams of documents to the state’s Library and Archives Commission for preservation. Among them are minutes of inaugural committee meetings, contracts and detailed expenses, down to a $500 outlay for a “Luckenbach Oompah” band and $21 to Fred’s Fruit Stand in 1979.

Richards’ inaugural in 1991 include guidelines for commemorative souvenirs — “no junk; no items not environmentally sound” — and letters inviting celebrities like Tina Turner to perform, in which Richards hints that Texans will be spared “another four years of Republican waltzes at state functions.”

Exhaustive files were also preserved for the next inaugural, after George W. Bush defeated Richards to become only the second Republican governor in Texas since the post-Civil War era. According to minutes of inaugural committee meetings, its chairman, Don Evans (who later became U.S. commerce secretary), “spoke about his desire that the staff sign an ethics statement.”

At one meeting in December 1994, “emphasis was placed upon the facts that the inaugural committee should be considered a ‘state agency’ and its funds, staff and property should not be used for anything other than the planning and funding the inaugural, conducting the inaugural and keeping the necessary records in compliance with the statute,” minutes show.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/bdae1452aff6d5354139eaf0d40ed597/Inaugural%20Documents%20Archive%20SN%20TT%2004.jpg)

Detailed memos and planning documents from the time capture everything from a proposal for “personnel with carts and shovels to follow behind horse units [in the inaugural parade] to pick up horse droppings” ($750) to repeated asides that corporate money would be used to make the events more affordable to the public.

Even after inaugural committees are dissolved, bills can keep coming in — and the law says the state has the authority to pay them. That happened after Abbott’s first inaugural in 2015 when records management company Iron Mountain submitted an invoice for $110.

The secretary of state’s office then “contacted a committee member and determined this claim is valid,” according to a letter obtained by the Tribune.

The purpose of the expenditure: document shredding.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Shannon_Najmabadi.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Jay_at_Cloak_TT.jpg)