For three Texas universities, firing their football coaches in 2018 could cost almost $7 million combined

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2015/09/01/UHsports_ZbPSyXO.jpg)

After disappointing football seasons led to swift firings, three Texas public universities now effectively have two head football coaches each on their payrolls — turnover that will cost the schools $6.9 million in payouts to their departing coaches, and more than $9 million this year to hire replacements.

At two of the three schools, Texas State University and the University of Houston, the football programs spent more money than they earned last fiscal year, requiring other university funds to cover the difference. Texas Tech University, whose football team made $19.6 million more than it spent in 2017, owes a former coach a $4.2 million payout, and will spend some $3 million this year on his replacement.

The payments come at a time when many Texas colleges have continued to raise tuition and fees, in part to compensate for declining support from the state Legislature. But university officials say that winning on the gridiron is a net positive for the school, one that can bring name recognition, prestige and the possibility of lucrative licensing deals and increased ticket sales.

“Higher education, like college athletics, pleads poverty all the time. But our actions certainly don't support that,” said David Ridpath, a former assistant athletic director, and a sports administration professor at Ohio University. “We're kind of on this perpetual hamster wheel of just trying to one up each other.”

Some states, like Illinois and Florida, have introduced legislation to cap severance pay at 20 weeks of a public employee’s salary, citing a desire to curb “golden parachutes” funded by taxpayers. But the same restriction doesn't apply to Texas coaches, and each of the eight public schools that play top-level college football in the state have made a payment to a departing coach since 2015.

UH, for example, parted with former head football coach Major Applewhite in December, giving him up to a $1.95 million payout and $500,000 in deferred compensation. The school is also paying $20 million over five years to Applewhite’s replacement, Dana Holgorsen — and another $1 million to Holgorsen’s previous employer, West Virginia University, to buy out his contract there.

Texas State, which fired former head coach Everett Withers in November, owes him a $737,500 payout — just less than the $800,000 annual salary negotiated for Withers’ replacement, Jake Spavital.

Elsewhere, the University of North Texas promised a coach fired in 2015 more than $2 million, and the University of Texas at San Antonio and the University of Texas at El Paso have both paid former head coaches that stepped down.

UH officials did not detail Applewhite’s payout at a January press conference announcing Holgorsen’s hiring. But system officials suggested its athletic department would become financially self-sustaining, and that coach turnover could be crucial to its success.

"A mediocre program is not an asset, it's a liability, and I want to have an asset," said UH Chancellor Renu Khator. "If you want to be nationally-relevant, there are certain important elements ... and one of them is having a winning program."

Multi-million dollar payouts are nothing new in the competitive and often-lucrative realm of college sports. But experts say the increased churn reflects the big money at play, and the mounting pressure coaches are under to win. Even small programs have seemed to adopt an aggressive approach to hiring in the hopes that the right coach can recruit talented players, drive up ticket sales and inspire boosters to donate.

Robert Lattinville, an attorney who specializes in sports employment contracts, said that athletic directors, influenced by their fan bases, have in turn “gotten less and less patient” to see results.

“They’re less willing to give a coach an extra year or two to round out his recruiting base to develop the talent,” he said. If you’re a coach, “You’re getting fired earlier in your tenure and the earlier you get fired on a long-term guaranteed contract, in most cases it means the more you’re paid out.”

In few states are the payouts larger than in Texas, home to some of the country’s most profitable college football programs, the University of Texas at Austin and Texas A&M University.

UT-Austin, which generated $100.1 million in profit from its football team last fiscal year, made a $9.4 million payout to former head coach Charlie Strong in 2017 and 2018, while also paying around $10.75 million to new coach Tom Herman. The year before, UT-Austin gave UH $2.5 million to buy Herman out of a contract he had with the school.

A&M, whose program made $66.8 million in profit last year, fired then head coach Kevin Sumlin in 2017, gave him a $9.9 million payout, then hired Jimbo Fisher for a record-setting contract worth $75 million over a decade. Had Fisher been fired without cause in December, A&M would have owed him around $68 million — the largest possible payout in the country at the time.

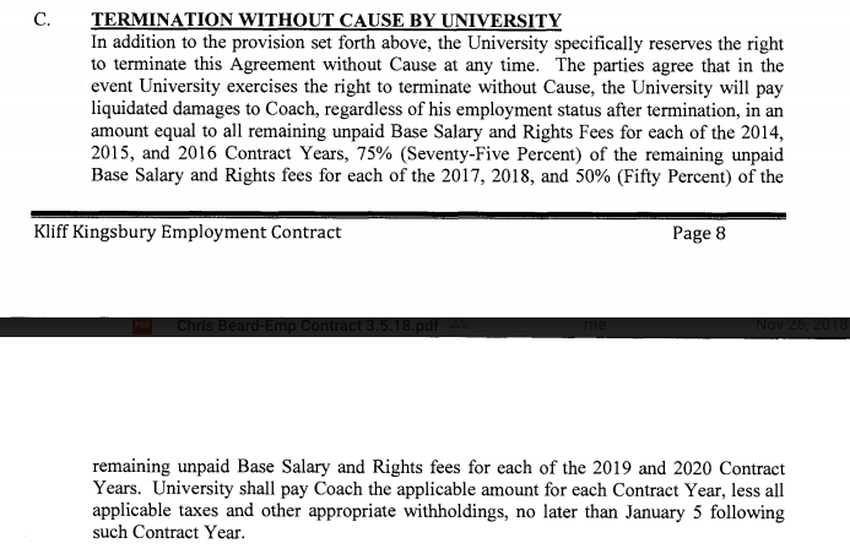

And Texas Tech University, whose program brought in $19.6 million in profit in the 2017 fiscal year, fired head coach Kliff Kingsbury in November, and will pay him $4.2 million for the two years that remained on his contract. Tech also paid Utah State University $800,000 to hire away coach Matt Wells — and will give him an annual average $3.1 million as part of a six-year deal worth more than $18 million.

"Is it worth it? I say it is," said Texas Tech President Lawrence Schovanec. Football "is a terribly important part of our marketing. It creates enthusiasm among the student body as well as among alumni and supporters that otherwise might not have any connection to the university."

The revenue generated by the program is used to fund other sports teams at the college, he said — "you couldn't have a lot of the sports without" it.

Similarly, UT-Austin spokesperson J.B. Bird said the school's team kicks some of its revenue over to other parts of the university. The football program is among the few nationwide, he said, "that receives no revenue from student fees, institutional or state sources," and actually made some $10 million for student services and the school's academic enterprises in 2017.

Even colleges whose football programs were not profitable in 2017 highlighted the benefits their teams bring, including exposure, alumni engagement and donations. UH has, in fact, made money off some of its departing coaches — several of whom have been hired by other schools who had to first buy out their contracts with UH.

Payouts are made when a university fires a coach without cause before his contract is up. Often, the coach is required to make a good faith effort to find a new job, and the university’s payout is lessened based on the coach’s future employment. If a coach breaks his or her contract, the university may in turn be owed buyout — a tab frequently picked up by the coach’s new employer.

The buyout or payout terms specified in the coach’s employment agreement would not apply if the coach is fired for misconduct.

“The concept behind payouts often is flawed because by definition, you're not offering that money unless they've underperformed relative to your standards,” said Lattinville, the attorney, who works for the firm Spencer Fane LLP. University officials may feel they are competing for high-demand coaches that are “non-fungible,” he said, lessening the school’s leverage to set more favorable payout terms.

Lawmakers in several states have restricted public-sector severance in a way that could “help their colleges negotiate better deals,” Lattinville said. A measure in Illinois, that went into effect this month, was introduced after a series of high-priced payouts were granted to university administrators, causing a stir.

The Illinois law mirrors a statute in Florida, that also bars severance at 20 weeks’ of pay, and is similar to a measure in place in Minnesota. California and Idaho also cap severance pay for government employees, though higher education institutions are excluded.

Rachel Leven, policy manager for the Chicago-based Better Government Association, helped push for the Illinois law. She said the organization heard an argument from public officials that “we're competing with the private sector and if we can't provide a severance then we're not going to get top talent.”

“That's one of the reasons that we liked the 20 weeks piece of it. We said, ‘Well, sure, there is a reasonable framework in which severance can be offered as part of a contract, but it can't just be a blank check,’” she said. “This is just a way to help people in Illinois trust their own government more.”

Many experts don’t expect there to be an overhaul in how college coaches are paid, or broader changes made to universities’ spending on athletics.

Lattinville, the attorney, said a well-known coach will excite a university’s fan base and energize donors in a way that hiring someone equally-skilled, but lacking in notoriety, won’t.

“There's the reality and then there's the perception,” he said. “The perception can be every bit as important.”

Andy Schwarz, an economist specializing in antitrust and college sports, said football is “part of what makes a college look like a college, and makes it a desirable place to go” — “just like the English department.”

When the University of Alabama at Birmingham cut their football team, he said, student enrollment declined. When the institution restored the program, it leaped back up.

Still, Schwarz said there are “perverse” trends in coaches’ pay that are unlikely to change, due to the NCAA rules that govern amateur athletics. Because student-athletes cannot be paid under the NCAA regulations, money generated off college sports flows instead to the “means of attracting them,” said Schwarz — whether that’s building the nicest facilities or hiring coaches that will galvanize recruits.

“They're using those coaches to attract, to bring in good talent,” said Schwarz, who favors "ending the collusive agreement among all NCAA members not to pay" student-athletes.

“So you have to signal, to signify, to the athlete that he can count on the coach being there for the long-term. Well what's a good way to signal that?” Schwarz said. “If we fire him, we're going to have to pay him a lot of money.”

Disclosure: The University of Texas at Austin, Texas A&M University, the University of Houston, the University of North Texas, the University of Texas at El Paso, the University of Texas at San Antonio, Texas Tech University and Texas State University have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

Reference

Dana Holgorsen's memorandum of understanding with the University of Houston.Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Shannon_Najmabadi.jpg)