"Somebody had to push": One couple's fight to change how Texas defines a pickle

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/bae2978b46dca10f3c538aa5157f2247/Pickle_1_LS_TT.jpg)

HEARNE – In 2006, Anita and Jim McHaney were in an urban rat race. Retirement was still years away for the couple, who were working as a nurse and engineering consultant in Houston, but they'd already sketched out an ambitious second act that would boost their retirement savings and get them out of the city.

Their plan: Retire and bring in extra income by selling fresh and pickled produce at farmers' markets. They spent their weekends scouting out properties before buying a 10-acre tract of land in Robertson County — a grassy expanse with a winged elm tree — and naming it Berry Ridge Farm.

“We’re country kids,” said Jim McHaney. They’d both worked to “get the heck out of the country and go to the big city,” and now they were yearning to return to their roots.

When Jim McHaney retired in 2013, the couple started growing their first crops there — kale, collard greens, beets — which they tied with twine and sold by the bundle at a Saturday morning market in Brazos Valley. With just the two of them tending the farm, it was physically exhausting work. Still, they had early success.

“We’ve been selling out every week,” Anita McHaney told a local paper in 2014. They found their land was particularly conducive to growing root vegetables — “you would not believe the beets we grew,” Anita McHaney said. The only crop they struggled with, she noted, were cucumbers.

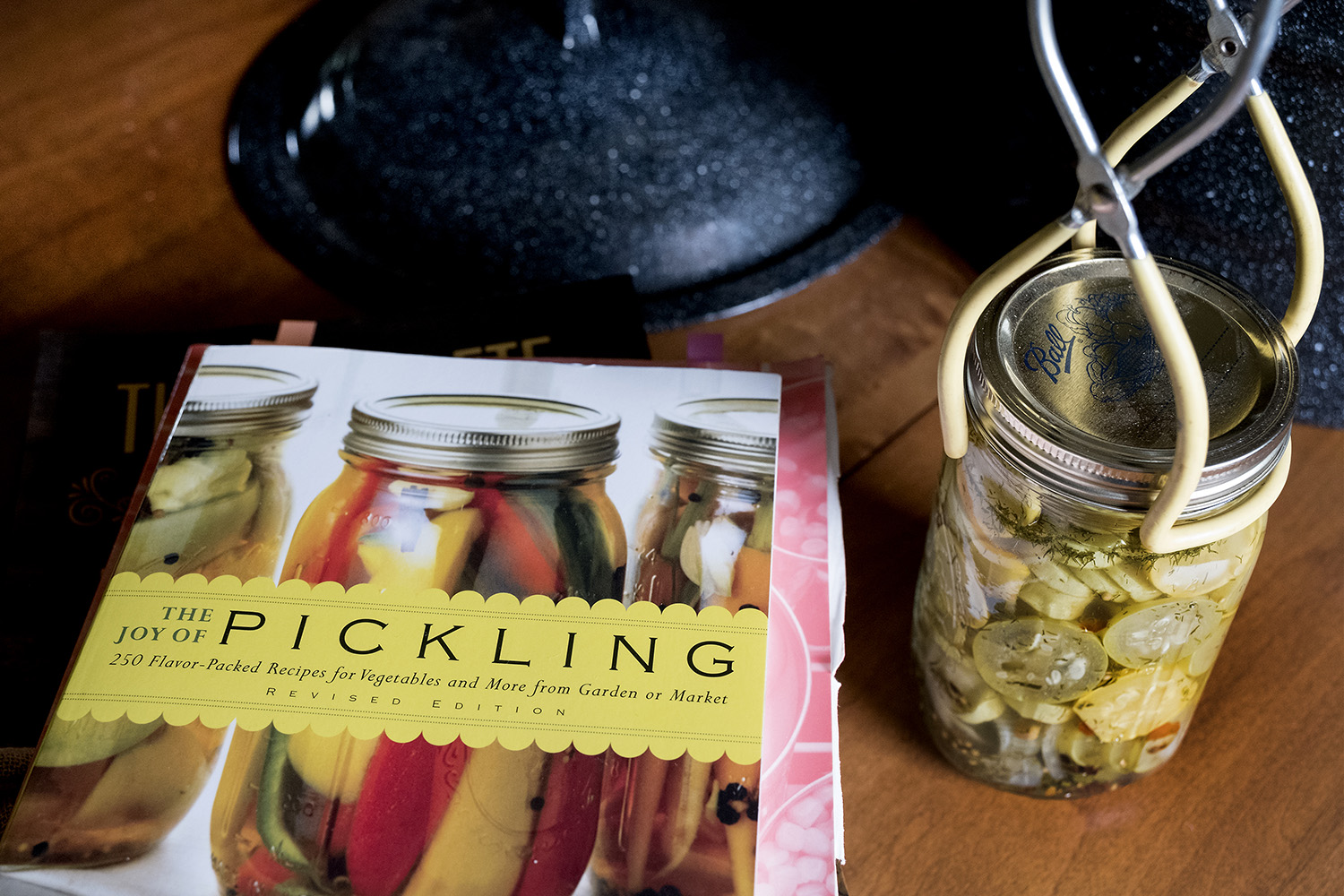

Selling pickled produce had always been part of the McHaneys business plan. Pickles were a “value-added product,” Jim McHaney explained, that could be sold on a schedule not tethered to the seasons. The couple wanted to sell pickled beets — maybe even pickled peaches, okra and carrots; and they thought they could under a five-year program that lets mom-and-pop businesses in the state peddle homemade pickles and other products at farmers' markets.

But as the McHaneys tried to set up their small-batch pickling operation, they realized there was a major obstacle. A recently-approved state regulation defines a pickle as one item and one item only: a pickled cucumber. Not pickled beets. Not pickled okra. And not pickled carrots.

In Texas, a state where political leaders often extol the virtues of entrepreneurship and light-handed regulation, purveyors of pickled cucumbers can take an online course, meet a few other requirements and then set up shop at a farmers’ market. To sell any other kind of pickled fruit or vegetable, however, the McHaneys learned they would have to become licensed “food manufacturers” — a designation that would require them to install a commercial kitchen, get a license and pay hundreds of dollars to take a course they deemed unrelated to their home-pickling business.

“It turns out it's just very difficult to meet all of the rules to make a pickled beet. You'd think that it would be easy, but it’s not,” said Anita McHaney. “Every time we thought we had figured out what we had to do to meet all the rules, we found another one.”

By 2016, after three years of tending to their farm and selling fresh produce at the farmers’ market, the McHaneys had had enough. They sat on plastic chairs under the winged elm on their farm and thought, “We’re working ourselves to death and not making any money,” Jim McHaney remembers. “This just is not practical; this is just not a sustainable business.”

The McHaneys had been writing letters to bureaucrats and visiting with lawmakers, trying in vain to understand why the word “pickle” had been defined so narrowly in the state’s administrative code.

But the couple still had one gambit left to try: They decided to sue the government for infringing on their economic liberty.

“All other pickled vegetables are prohibited”

The regulation that sank the McHaneys farm seems to have been added as an afterthought.

A Texas law, passed in 2011, allows bakers to sell their home-baked goods without being licensed food manufacturers — an expensive and burdensome undertaking for a retired couple. In 2013, another law extended this exception to pickles, popcorn and other food products — allowing some entrepreneurial Texans to hawk their products at festivals and farmers’ markets after checking a few boxes.

(To meet the requirements of the law, often called the Texas Cottage Food law, sellers must make less than $50,000 in gross annual income off the goods they are selling — and the products can only be sold in certain venues, like farmers’ markets and fairs, and not online.)

“It turns out it's just very difficult to meet all of the rules to make a pickled beet. You'd think that it would be easy, but it’s not.”

— Anita McHaney

When the laws passed, they were heralded as a win for small-business owners and in the spirit of Texas’ pro-market environment. The only concern raised in hearings about the bill was that freeing home cooks and farmers from the requirements of being a licensed food manufacturer could lead to public health problems.

No one seemed to anticipate a hitch over the definition of the word “pickles.”

The first attempt to define what “pickles” are appears to have come from the Department of State Health Services, a state agency that protects public health. While legislators didn’t specify what “pickles” are in their version of the Cottage Food Law, the state health services department — tasked with turning the law into rules — did define it.

“Pickle -- A cucumber preserved in vinegar, brine, or similar solution, and excluding all other pickled vegetables,” officials at the agency wrote into the state’s administrative code in 2014. The department’s website underscores the pickle distinction in an FAQ section: “Only pickled cucumbers are allowed,” it says. “All other pickled vegetables are prohibited.”

“What in the world?” Anita McHaney remembers thinking when she heard how the word pickle was defined. She began calling the department, writing certified letters and eventually tracked down the agency’s internal ombudsman. She says she was never able to get a clear answer as to why the pickle definition only covers cucumbers.

“It’s myopic,” said Virginia Cox, another vendor at the Brazos Valley Farmers Market, who sells pickled cucumbers. She says “a weekend doesn’t go by” when she’s not asked whether she sells other kinds of pickled produce. “There's such a variety of fruits and vegetables out there that you can pickle, and it's exactly the same process.”

A spokesperson for the state health services department, Chris Van Deusen, said the pickle definition is based on lawmakers’ language. The legislation they passed, he said in a statement, “sets out a specific list of items that cottage food producers may make and sell, including ‘pickles.’ It doesn’t refer to other pickled vegetables, pickled foods or pickled products, so we used the most common and generally understood definition of pickles: cucumbers.” Agency officials don't remember there being comments or objections to the "pickles" definition during the rule-making process.

It’s tough to explain that logic to customers, Jim McHaney said. “They come and say, ‘Well why don’t you have pickled okra, like this?’” he said, holding up a jar the couple had pickled for their own consumption. “You have to explain, ‘Because the regulations won’t let me do that unless I jump through all these hoops.’”

He said customers respond: “Who said? Who’s the den mother making these decisions?’”

Lawsuit filed in the name of "economic liberty"

The legislator who authored the 2013 law, state Rep. Eddie Rodriguez, D-Austin, told The Texas Tribune in a recent interview that he’d had no idea that the department’s rules had construed “pickles” to mean pickled cucumbers only.

“That pickle definition is kind of flying in the spirit of the legislation,” he said. “I don’t know if this was an intentional thing on the department’s part or not, but if the net effect of it is to really narrow the legislation in a way that was not my intent ... they may be legislating a bit by rule.” Rodriguez, who has filed other bills related to the Cottage Food Law in the intervening years, says he may sponsor similar legislation in 2019, the next time the Legislature is set to meet.

In the meantime, the McHaneys decided to shutter their farm; they said it just was not profitable if they couldn’t sell pickled produce. They fed the excess beets they’d grown to a neighbor’s cows, and their farmland is now overgrown with grass.

But the couple didn’t give up. Last year, they presented their case to a public-interest law firm, the libertarian-leaning Institute for Justice, which connected the McHaneys to Dallas-based lawyers willing to work pro bono.

They've announced they'll file a lawsuit Thursday against the state health services department, accusing the agency of frustrating the financial viability of the McHaney’s farm and of violating the couple’s constitutional right to “earn an honest living in the occupation of their choice, free from unreasonable governmental interference.”

It’s a matter of economic liberty, a draft of the petition says. “There is no reason to treat pickled beets differently than pickled cucumbers, and the Department has not even attempted to articulate its rationale for doing so.”

The McHaneys are seeking compensation for their court costs. But they mainly hope to stop the state health services department from enforcing the pickle definition and to have the law declared unconstitutional.

Sitting at their kitchen table, strewn with books with titles like “Making Your Small Farm Profitable,” the couple reflected on the case in mid-May.

“Somebody had to push, and waiting for somebody to push for you wasn't working for us,” Jim McHaney said.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Shannon_Najmabadi.jpg)