Texas A&M spent more than a quarter-million dollars to draw attention from Richard Spencer's 2016 visit to campus

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2016/12/06/TAMU_Protest2TT.jpg)

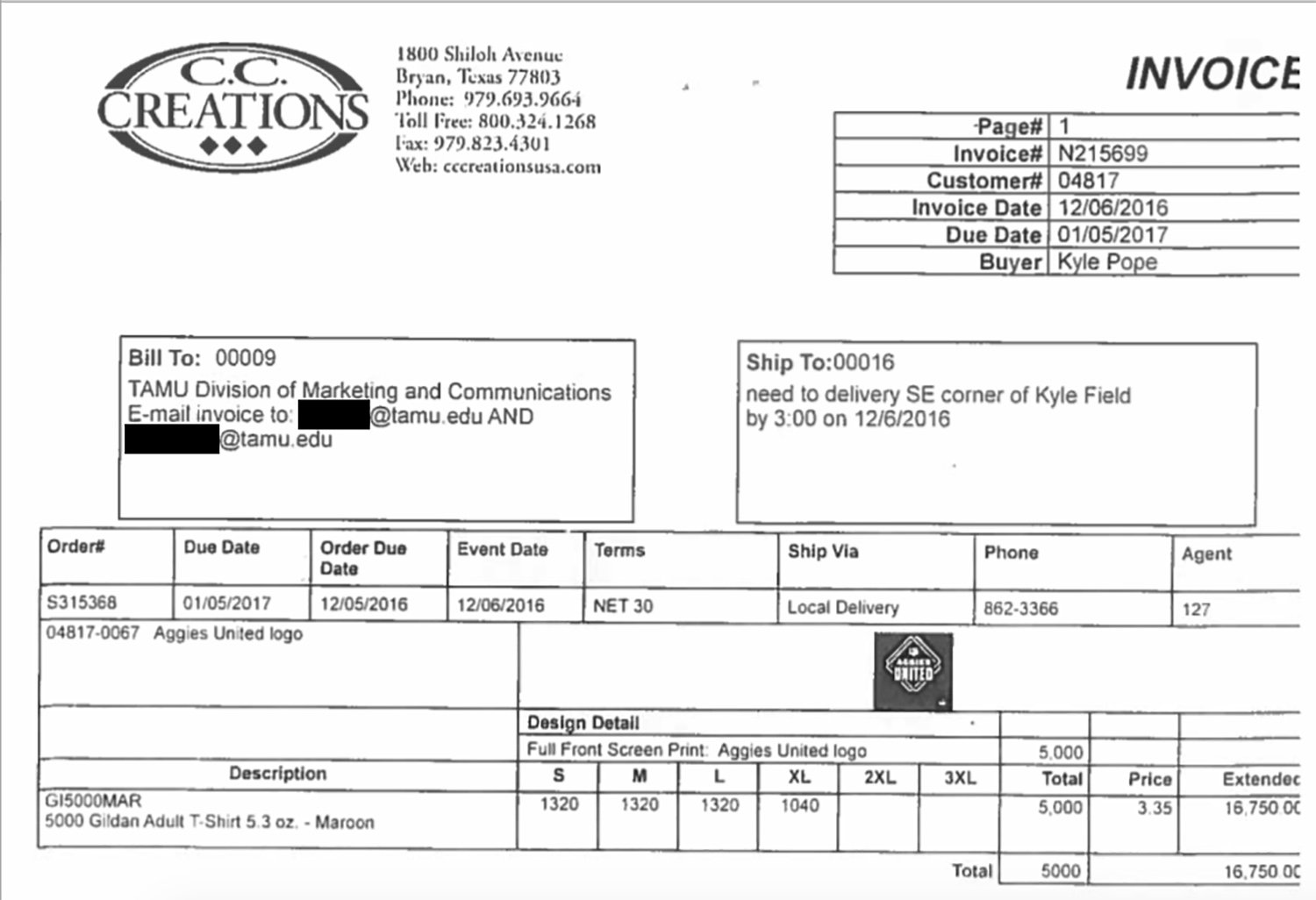

Seventeen thousand dollars on t-shirts. $11,000 for flashing LED bracelets. $60,000 for big-name musicians and a string quartet. $9,500 for an “expression wall” that event attendees could draw on.

Texas A&M University officials decided it was worth paying those costs and more to divert attention from a controversial speaker's visit to campus in December 2016.

While lawmakers and campus administrators agree that protecting free speech on college campuses is essential, doing that can be expensive for schools. Take A&M. When a self-described leader of the "alt-right" movement, Richard Spencer, came to the College Station campus that year, A&M held an "Aggies United" event that filled the university's football stadium with musical acts and feel-good speeches.

The cost of that three-hour rally? Around $299,000 – or nearly $100,000 an hour.

“Knowing that the world would be watching this event at Texas A&M University created the challenge of allowing open dialogue under a heavy security presence but also provided an opportunity for us to demonstrate Aggie values — both to those unfamiliar with A&M as well as to Aggie families and former students — through a large-scale university-sponsored event,” said Kelly Brown, a university spokeswoman.

“Executing these plans came at a cost,” she said. But all the money for the rally — which was planned in 10 days — came from discretionary funds used for holiday parties and other events. “No parent or student was financially burdened since no state dollars were used to pay” for the event, she added.

How to promote free expression on college campuses has stymied the Legislature — no bills to address the issue passed last year. And though lawmakers and university officials tout the importance of free expression, administrators confronted with a controversial speaker’s visit to campus seem to have few good options at their disposal:

- Hold the event and pick up a hefty tab for security officers

- Charge the host group for security and risk stoking a social media firestorm

- Or cancel the event and face the threat of a lawsuit, legal fees and a barrage of criticism about yielding to a “heckler’s veto.”

Those vetoes — which happen when officials suppress speech out of concern for how others will react — have drawn particular concern from lawmakers, who often say the answer to hateful speech is more dialogue, not less.

A&M officials tried to take that route in 2016. In the lead up to Spencer’s visit, A&M President Michael Young met calls to cancel the talk by citing the First Amendment and the importance of free expression. He issued a lengthy statement saying the university would, instead, host its own gathering the same evening.

The counter event, the university said in a recap on its website, served as an outlet for students and a positive antidote to the negative media attention.

“For anyone watching or reporting on the Spencer event, we hoped our message of hope and positivity would shine through, as well,” Brown said. “And we believe it did.”

But those three hours cost the university nearly $300,000 – roughly $50 for each of the 6,000 people that attended. The school spent $66,000 to rent and staff the school’s football field, and $4,000 for different insurance policies.

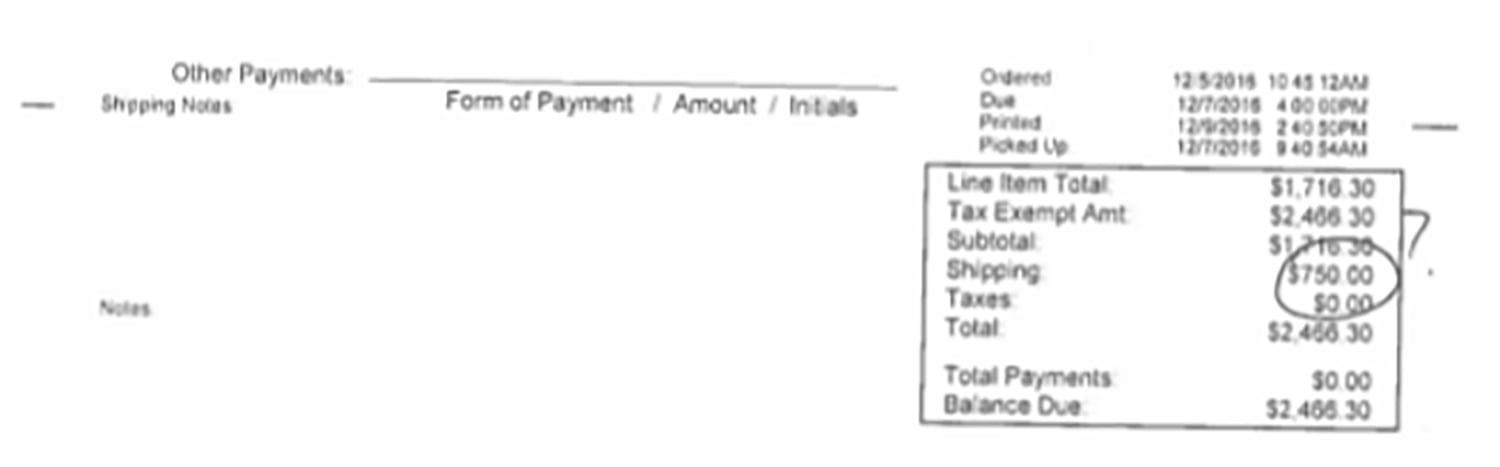

The figures were found in nearly 100 pages of receipts and invoices provided to The Texas Tribune through an open records request. Among the charges were $50,000 the university paid to book the musician Ben Rector, $1,700 for a huge banner, $750 to ship that banner, $5,000 for food like “an elaborate display of seasonal local and tropical fresh fruits” ($995), and 100 deluxe sandwich boxes ($878.50).

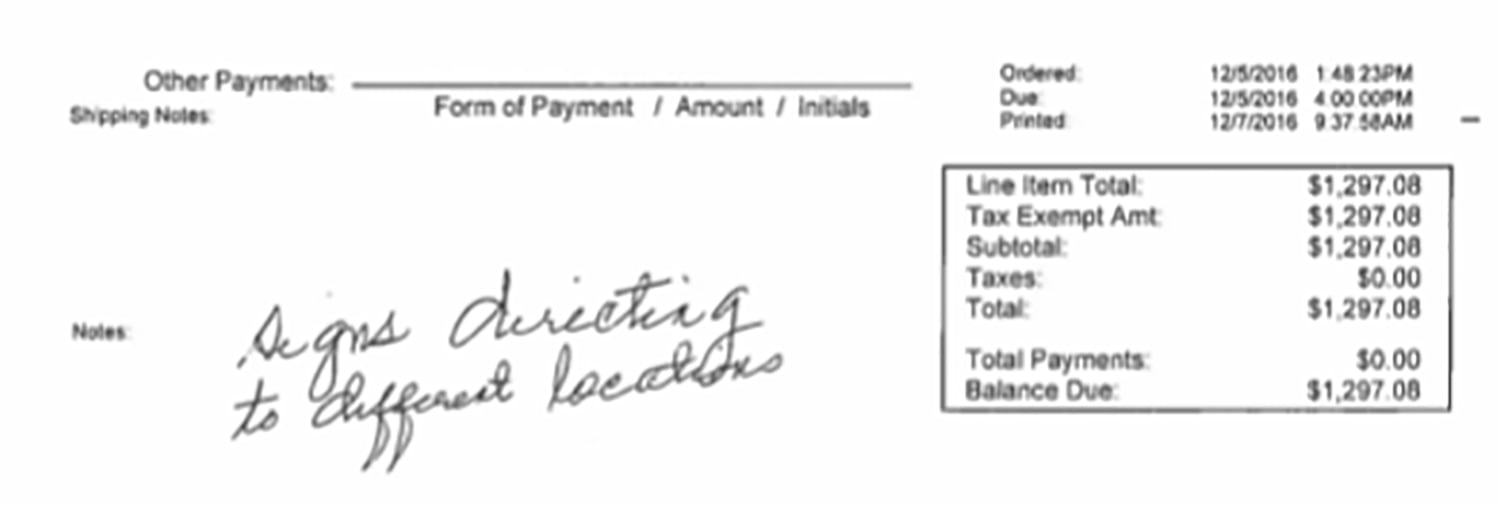

$1,700 was spent on buttons and, according to a handwritten note scrawled on one receipt, $1,297 was used to purchase “signs directing to different locations.”

The expenses spent on A&M’s own event dwarfed the price tag attached to Spencer’s speech – the one school officials were trying to draw attention away from in the first place. Records show a private citizen paid the university about $3,500 to rent a room on-campus for Spencer to speak in and to pay for four security guards.

Twenty-thousand dollars were also spent on law enforcement – from four different police and sheriff’s departments – to handle the Spencer event, the Aggies United rally, protests and traffic control.

"Evidence of our commitment to free speech"

At a January hearing about campus free speech, Texas A&M University System’s general counsel told a panel of state lawmakers that the school’s handling of Spencer’s 2016 visit was “evidence of our commitment to free speech.”

A&M officials let the event go forward despite facing significant pressure to cancel it – and “we did so at great expense given the strong security presence that was required to manage the crowd,” the general counsel, Ray Bonilla, said.

He said that after Spencer’s 2016 visit, A&M redrafted one of its free-speech policies to bar speakers who are not sponsored by a campus group from using school facilities. (Anybody can still give a speech in open areas on campus.)

And Spencer wasn’t able to make another appearance at A&M – despite being slated to attend a September 2017 “White Lives Matter” rally at a permissible area, an outdoor plaza on campus. Lawmakers called on A&M leaders to bar the event from happening and school officials canceled the rally soon after, citing safety concerns after a protest in Charlottesville – one referenced by event organizers – turned violent. The organizer of the rally threatened to sue the school after the second event was canceled, but has not.

“Aggies United event was a successful response but a lot has happened in the last 14 months since in dynamics,” Amy Smith, an A&M spokeswoman, said. “I worry that another counter program event such as that would actually draw out bad actors today and may not be apt to do it again.”

Disclosure: Texas A&M University has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune's journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Shannon_Najmabadi.jpg)