With no state-approved textbooks, Texas ethnic studies teachers make do

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2017/11/06/Ethnic_Studies_5_LS_TT.jpg)

When 16-year-old Adán Zylberberg was in need of a book about Malcolm X for an ethnic studies project, Elizabeth Close handed him a copy of "Malcolm X: A Graphic Biography," which brought to life the civil rights activist's history in vivid black and white drawings.

It was not an unusual pick for Close's students. During the six-week unit on civil rights, the ethnic studies teacher at Anderson High School in Austin taught her class from a wide array of sources: a college-level multicultural history book, teaching materials from the Southern Poverty Law Center, video clips from "The Daily Show," contemporary news articles and old photos of segregated public facilities from the Library of Congress.

She doesn’t think all that could fit into one textbook.

"It's a constant process to continue finding better sources, better connections, better ways to make it relevant to them," said Close.

The Texas State Board of Education will vote this week on whether to approve two ethnic studies textbooks — a Mexican-American studies textbook and a Jewish Holocaust memoir — submitted in response to a board request last November to offer approved texts aligned to the statewide curriculum. Last year, the board rejected a different Mexican-American studies textbook proposal that advocates and academics decried as error-ridden and racist.

Tony Diaz, an activist who helped get last year's book struck down, submitted "The Mexican American Studies Toolkit" in response to the board's call last year. If the board votes yes, Diaz's proposal would be the only Mexican-American studies textbook officially approved by the state.

But would Texas teachers actually use the book? That depends on the district.

Austin ISD developed its ethnic studies program over the past year, without additional state resources. But a smaller district might not have the staff or money to build a program from scratch, educators said. Texas does not require districts to choose textbooks the state board approves, but many administrators find it easier to use a state-vetted book rather than research other texts on their own to ensure they meet state standards, according to Texas Education Agency spokesperson Debbie Ratcliffe.

In 2010, Arizona state legislators banned ethnic studies for being too divisive, prompting a nationwide backlash that has, in turn, spurred enthusiasm for teaching the subject to high school students. (A federal judge later ruled the Arizona law violated students' constitutional rights.) Many advocates cite a Stanford University study showing Hispanic and Asian students who took ethnic studies in San Francisco high schools improved their grades and attendance.

In Austin ISD, one of the only districts in Texas with a multi-ethnic studies program, administrators and teachers started last fall figuring out what credit students would receive and what skills and concepts students would be expected to learn, said Jessica Jolliffe, the district’s social studies supervisor.

This year, nine teachers across eight campuses in the district offer a general ethnic studies class, looking at the histories of different ethnic groups and races within the context of U.S. history.

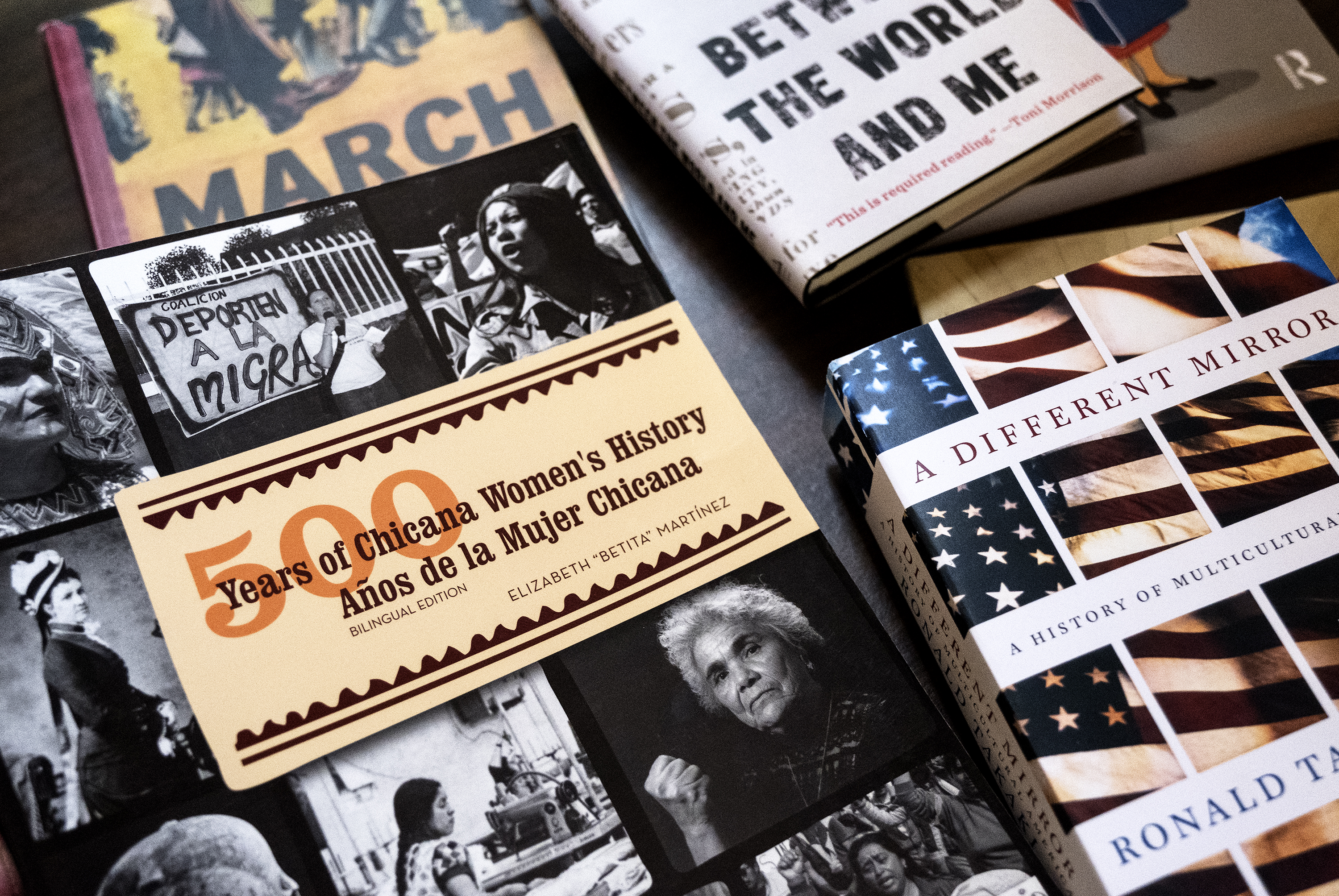

Rather than try and shoehorn such a sprawling, nuanced topic into a single textbook, Jolliffe bought copies of Ronald Takaki's "A Different Mirror: A History of Multicultural America" — a college-level ethnic studies resource — for each classroom, and then gave teachers a $500 budget to buy additional books to suit their classes' abilities.

Close found Takaki's multicultural history too advanced for most of her students, so her bookshelf is also filled with graphic novels, memoirs and illustrated histories of various ethnic groups. Diaz's book would not be particularly useful for her class, she said, since she already has a wealth of Mexican-American studies resources.

Yet for 15-year-old Chloe Hightower, having a traditional textbook would make Close’s ethnic studies class more convenient — and easier to explain to her friends, many of whom don't even know the school offers it. “I would love the idea of having a book we could get to read instead of having to look up everything,” she said. “People are not trying hard enough to make ethnic studies something people hear about."

That sentiment comes up a lot, Close said.

“The number one question from students is, ‘Why haven’t we learned about this before? Why did we have to wait for this optional class to get some of this?’” Close said.

The State Board of Education in 2014 rejected a push to approve ethnic studies as a new required class. Instead, the board put out a call for ethnic studies textbooks with the goal of making it easier for districts to offer relevant courses as general social studies electives. Since the board has not developed specific curriculum standards for ethnic studies courses, publishers can't know how many districts will offer them or what form those classes will take so they are less likely to spend time and money writing relevant textbooks for them, said Christopher Carmona, Mexican-American studies professor at University of Texas at Rio Grande Valley.

"That's one of many problems with the state board. They're asking us to create textbooks for a course that doesn't exist yet," Carmona said.

He leads a coalition attempting to advance Mexican-American studies in high schools across the state. He took an informal survey showing only about 30 teachers in Texas offer Mexican-American studies courses, either as a stand-alone course or dual-credit course with a local university. Most are along the border or in urban areas with higher percentages of Hispanic students.

Carmona, along with a few other high school teachers and university academics, informally reviewed Diaz's book to ensure it was academically sound. "There were a lot of things we had to fix," he said.

The group added in sections detailing crucial parts of Mexican-American history, such as the Supreme Court decision to give Mexican-Americans equal protection under the Constitution and Mexican-American involvement in the Civil War. The scholars also removed existing sections, including one essay that references drinking beer, thought to be unsuitable for high school students.

An earlier official state review of the book found similar issues. Diaz said he is addressing the errors found by both groups.

When El Paso ISD teachers were deciding on a textbook this summer for a new Mexican-American studies program, they read through Diaz's textbook proposal alongside several existing books already used in other districts. They decided not to use Diaz's book, in part because they were not sure it would get approved this fall.

Instead, teachers unanimously picked "Chicano! The History of the Mexican American Civil Rights Movement" by F. Arturo Rosales, which they found on a textbook list for a course Houston ISD offers.

"They said the language is more student friendly, it has more pictures, it gave students a chance to actually expand on it," said Velma Gonzalez Sasser, El Paso ISD student success coordinator.

This year, three high schools offer Mexican-American studies, and two middle schools have integrated Mexican-American studies into their Texas history classes.

Visiting a high school class recently, Gonzalez Sasser sat riveted as students discussed the 1917 El Paso-Juárez Bath Riots, which were sparked after a 17-year-old Mexican girl refused to submit to a toxic fumigation procedure federal officials were using to kill lice on Mexicans crossing the border and convinced others to do the same.

"I never heard of this in my life," Gonzalez Sasser said. "I went to school here. I've lived in El Paso all my life. I've never heard of it."

Disclosure: The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors is available here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Aliyya_Swaby_TT.jpg)