Oilfield sand miners encroaching on threatened West Texas lizard

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/sagebrush-lizard-m.png)

A voluntary plan the state of Texas crafted to protect a tiny West Texas reptile — and avoid its listing as an endangered species — is facing a significant threat from companies that mine the fine-grain sand oil producers use for hydraulic fracturing.

That’s the central message of a letter Texas Comptroller Glenn Hegar’s office sent late last week to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service updating the federal agency on the status of the “Texas Conservation Plan” for the dunes sagebrush lizard.

The Fish and Wildlife Service proposed listing the sand-colored critter as an endangered species back in 2010 primarily due to loss of habitat from oil and gas drilling and ranching operations in the Permian Basin — an oil-rich region that spans West Texas and southeastern New Mexico and also is home to the threatened lizard. But industry groups complained that an official listing, which would have severely restricted development in areas inhabited by the species, would hinder oil and gas production at a time when new drilling technologies were bringing new life to old oilfields.

After that, then-Comptroller Susan Combs — wielding a newfound oversight of endangered species — worked closely with the oil industry and others on a plan to protect the threatened lizard, recruiting a variety of energy companies as participants.

Now, one of industry’s most important suppliers is threatening to derail it.

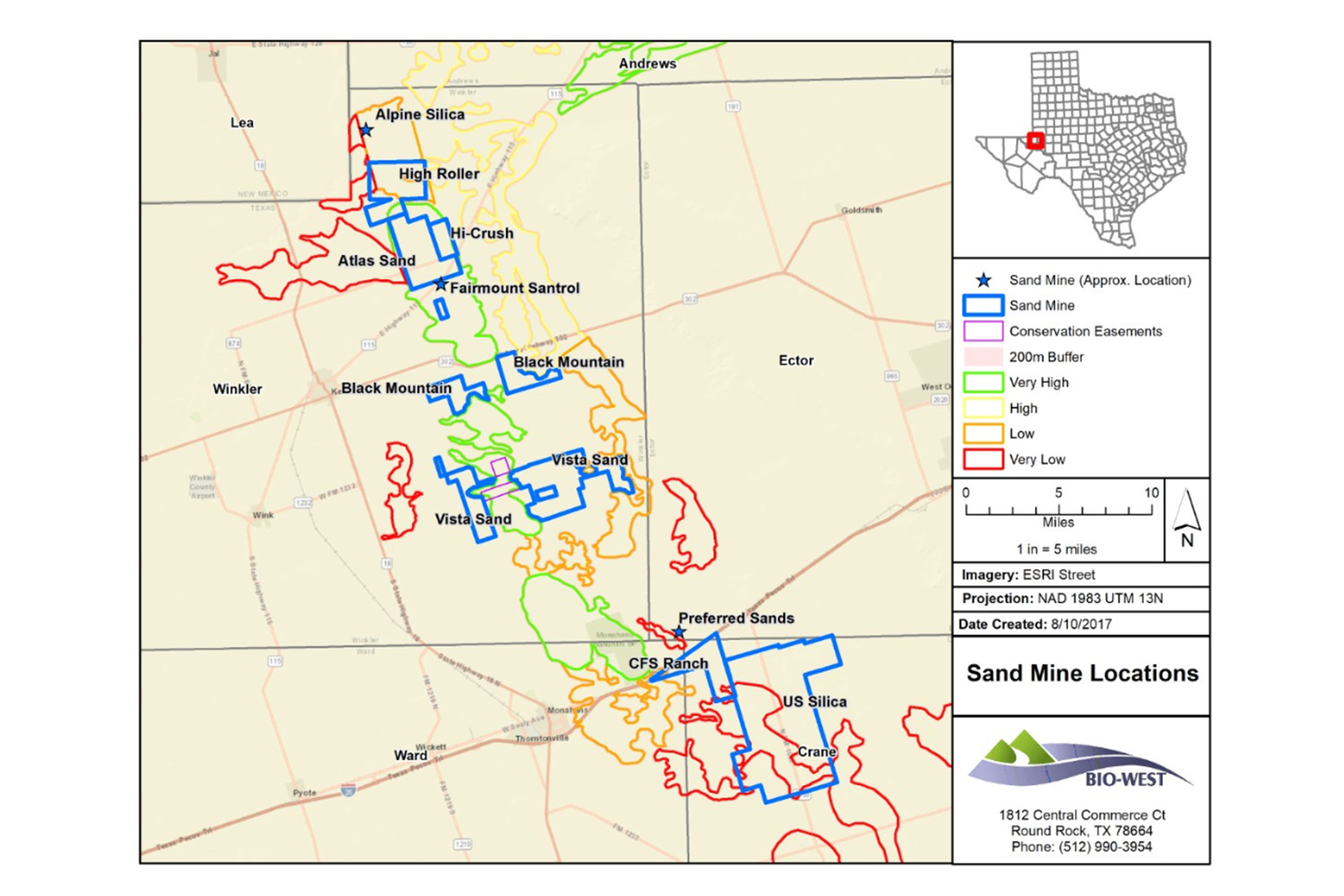

In a letter to the Fish and Wildlife Service on Thursday, Robert Gulley — the head of the comptroller’s Division of Economic Growth and Endangered Species Management — said that more than a dozen “frac-sand” companies are planning mining operations in four West Texas counties that are home to prime dune sagebrush lizard habitat.

While most of the 15 companies that have begun or are currently planning to mine sand in the area have expressed a willingness to revise operations to help protect the threatened reptile — and four have taken major measures to do so — the letter says that 11 still are planning to excavate in areas where several lizards have been sighted.

“Frac-sand operations could significantly impact [dune sagebrush lizard] habitat, including habitat in or near areas where lizards have been found in recent surveys,” Gulley wrote. “Moreover, the destruction of that habitat has already begun.”

The comptroller’s office “has no authority to stop the development of frac-sand operations of non-participants in the [Texas Conservation Plan],” he added, promising to keep the federal agency updated as the office has since the implementation of the conservation plan in 2012.

In an interview, Gulley told the Tribune it’s too soon to say how big an impact the mining operations will have on the dunes sagebrush lizard and the plan to protect it — it’s a relatively new but fast-developing factor that popped up only this year, he said — but that they definitely pose a “significant threat.”

Recent news reports have detailed a rush by several sand plants to get up and running in the Permian Basin as analysts expect half of next year's U.S. sand demand to come from West Texas.

While the comptroller’s office may successfully encourage some of those companies to revise their projects to minimize impact on habitat, Gulley said, “I don’t think we’re going to see any dramatic shifts.”

“I think they’re pretty locked down,” he said.

Of particular concern is that most of the planned mining projects — one already is operational — closely track a horizontal swath of prime dunes sagebrush lizard habitat. That’s because both the lizard and frac-sand mining operations prefer the same kind of sand, said Gulley, a renowned expert on environmental law and endangered species whom Hegar hired to oversee the office's endangered species division in 2015.

The division alerted Fish and Wildlife to the threat by frac-sand companies offline several months ago, Gulley said, deciding to officially alert the agency last Thursday after it had confirmed lizard habitat already had been disturbed.

About 270 acres have been impacted since March by frac-sand companies that aren't official participants in the conservation plan, according to satellite data and in-person observations Gulley's office has collected. That’s compared to the 296 acres that participants have disturbed since the inception of the plan in 2012.

Fish and Wildlife spokeswoman Lesli Gray said the agency is “continuing to monitor the situation and work with the comptroller’s office.”

The federal agency declined to list the lizard as endangered in 2012 and enthusiastically accepted dunes sagebrush lizard conservation plans from Texas and New Mexico, touting them as “landmark” and “a great example of how states and landowners can take early, landscape-level action to protect wildlife habitat before a species is listed under the Endangered Species Act.”

Still, environmental groups sued over the plan in 2013, arguing it wouldn’t adequately protect the lizard due in part to its voluntary nature. (They ultimately lost the legal battle.)

The letter comes a year after the comptroller’s office quietly fired the oil and gas industry-funded organization charged with overseeing the conservation plan after it had failed to do the work it agreed to do, including monitoring oil and gas producers to ensure they were in compliance.

When Texas promised to protect the lizard, state officials entrusted the day-to-day oversight to a nonprofit foundation overseen by registered lobbyists for the powerful Texas Oil and Gas Association known as TXOGA, the state's largest industry group.

Gulley said TXOGA has actually been “quite helpful,” as the office tries to convince frac-sand companies to account for the conservation plan in their operations even if they aren’t members. (Two of the 15 companies the division is monitoring are on track to join, he said.)

Todd Staples, a former state lawmaker who now heads TXOGA, said in a statement: "Oil and natural gas operators and sand miners are in on-going communications regarding planned sand mining in and around the DSL [dunes sagebrush lizard] area."

"The oil and natural gas industry led in developing a careful, voluntary conservation approach to ensuring the DSL was protected," he said. "It is our hope that sand miners will take a similar approach, and operators are engaged in discussions on how best to encourage responsible development in a manner that protects the lizard and its habitat."

Disclosure: The Texas Oil & Gas Association has been a financial sponsor of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors can be viewed here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Kiah.jpg)