When school’s out, rural Texas towns struggle to feed their hungry kids

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2017/07/28/Food_insecurity_LS_10_TT.jpg)

Editor's note: This is the second of a two-part series about the declining participation in Texas' summer meals programs for students. You can read the first story here.

REKLAW — Clara Crawford tapped the horn three times. Seconds later, two young boys ran down the steps of their house, their mother waving goodbye from the porch.

Each summer, most days of the week, the 86-year-old Crawford drives a 1995 Ford cargo van 35 miles to gather up about 20 hungry children in Fairview, an unincorporated community in Rusk County, and the neighboring city of Reklaw. She takes them to a program she runs at a local community center where they can play basketball in the hot sun and get a full lunch plus a snack.

In this sparsely populated part of East Texas, where some houses don’t have regular access to potable water, for seven years Crawford and her blue van have been providing a summer lifeline to kids who otherwise might be home alone and without a healthy meal.

The Texas Department of Agriculture administers a summer meals program providing federal reimbursement for school districts and nonprofits to give out meals to hungry children — but in recent years, the program has failed to draw students in, with July participation rates crashing by 20 percent in 2016.

Experts and even the state have had trouble pinpointing exactly why, but they cite lack of transportation as the main reason rural Texas kids can't reach free summer meals available at hundreds of locations across the state. The federal government does not compensate school districts or nonprofits for getting students to and from the free meal sites.

Which is why folks like Crawford who are willing to drive kids to those meals are so important. Despite the tight pickup schedule, Crawford sometimes finds herself waiting several minutes longer than planned outside a particular house, hoping a kid will hear the honks and rush out. Most of their parents are working, or are stuck at home with illnesses or disabilities, she said.

“I hate to not get them if they want to come,” she said, peering over the steering wheel anxiously. Every summer, she considers giving up on this volunteer chauffeur gig. She’s old and doesn’t need the extra stress. But then she wonders: Who else would do it?

The need for volunteers like Crawford goes beyond this corner of East Texas. In the tiny Panhandle town of Quitaque, residents also struggle to find summer volunteers to help provide food to hungry children after the local school had to end its program. Rural communities across the state face similar challenges.

In Texas, more than 4 million people don’t always know where their next meal will come from, often resorting to skipping meals, buying less food or choosing between buying food and paying other bills. Though it’s decreased over the years, the percentage of people at risk of hunger in Texas is significantly higher than the national average.

Even in towns that have a summer meal program, “if a site’s half a mile from a kid’s home, they’re unlikely to walk up there, let alone five or 10 miles,” said Tim Butler, coordinator of child hunger programs at the East Texas Food Bank, which gets federal money to provide meals for program sponsors like Crawford who want to feed kids locally.

The food bank also pays for Crawford's gas and vehicle upkeep through a privately-funded "rural transportation grant." Without that extra financial boost, kids in Fairview might not make it to the community center.

The federal government used to offer similar transportation grants to rural organizations that sponsored free summer meal programs, but it ended them after 2008 when the funding ran out, calling them "cost inefficient" for supporting rural areas.

'It used to be a big community'

A lifelong Fairview resident, Crawford is related to many of the kids in the area, or knows them well enough that they're basically family. As she drove — never faster than a steady 45 miles per hour — she spun out the stories imprinted in the lush landscape crowded with pine trees. She pointed out the place where, at eight years old, she got paid $3 daily to plant tomatoes. The place where her dad drove a tractor on another man's farm. And all the empty places left by folks who moved to the cities.

“There used to be a lot of people here. Now they let their trailers rot here. It used to be a big community,” Crawford said ruefully.

Larger school districts in East Texas don't typically need someone like Crawford because they can usually offer their own programs, and sponsor others nearby. The East Texas Food Bank seeks to fill the smaller, more rural gaps across 26 counties and 20,000 square miles, in a region where one of every five adults and one in every four children is at risk of going hungry.

“There are tons of communities out there with little resources and low population,” Butler said.

Partnering with people like Crawford ensures the meal sites draw more kids, Butler said. “They know the people in the community. They know how to get something started. They know where the kids are.”

Besides the 20 kids Crawford drives to the community center, two or three wander over on their own, chattering and playing while the adults start to hand out food. At 14, Erica McCuin is one of the oldest in the room. She ends up watching over the younger ones, sitting and joking with them as they bite into cheeseburgers with whole grain buns and pick seeds out of orange slices.

She’s visiting her aunt for the summer two towns over and said without the program, she’d end up hanging around her aunt’s house. “I’d sit down and watch TV or play on my phone,” she said.

McCuin's aunt, Savannah Williams, is one of three women who found out about the program through the local church and volunteer to run it. They said they're determined to keep it going after Crawford someday turns in her car keys.

Panhandle volunteers try to restart summer meals

While volunteers in East Texas fight to keep kids fed, volunteers more than 400 miles away in a small Panhandle town are trying to bring back summer meals after the local school shut its program down.

In Quitaque — recently proclaimed the bison capital of Texas for its proximity to a herd of the shaggy beasts in neighboring Caprock Canyons State Park — a third of the 478 residents lives below the poverty line, nearly double the state average, according to recent Census estimates.

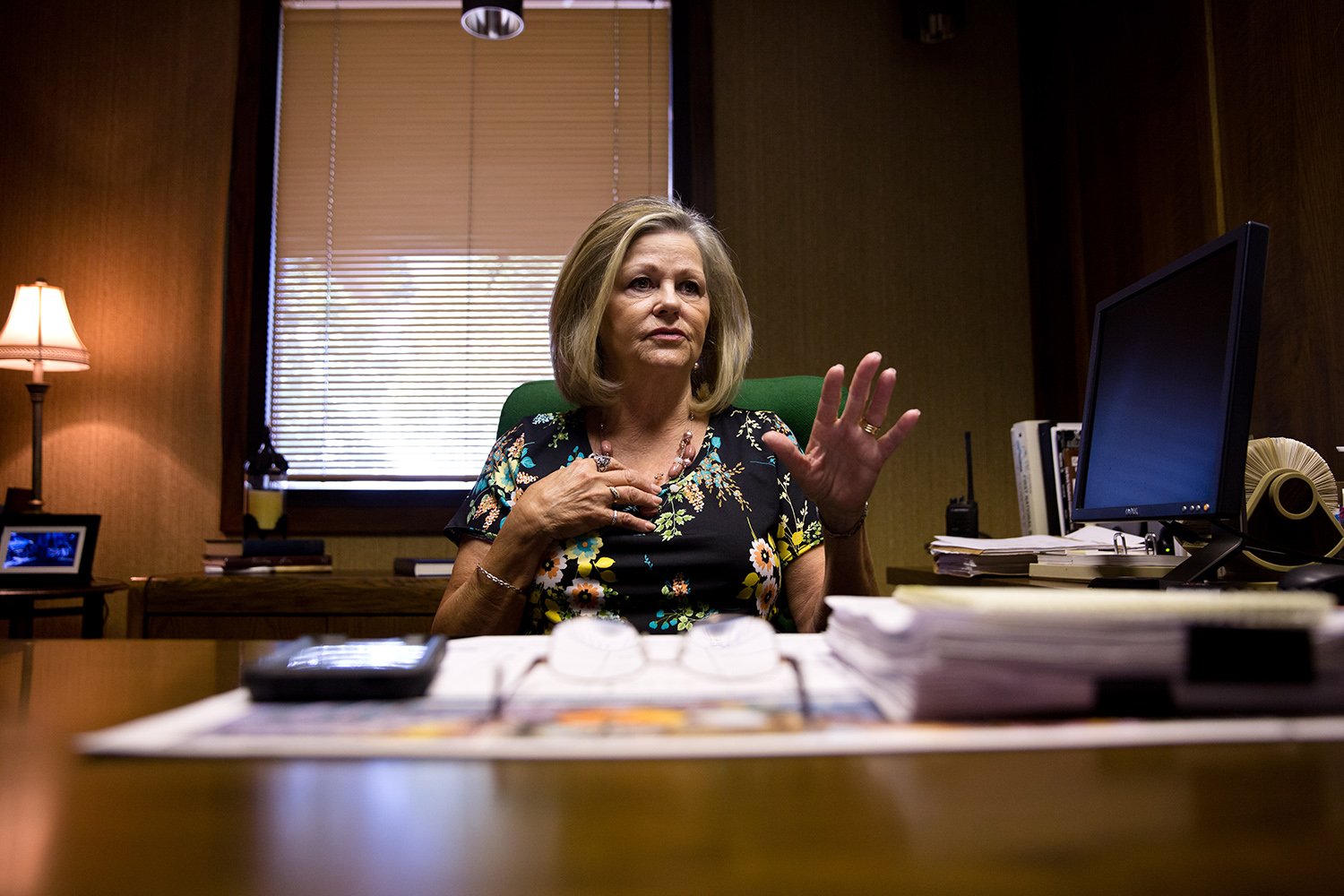

Kay Calvert wears a few hats for Quitaque, as a founder and president of the local emergency food pantry and assistant vice president at First National Bank. She’s working with a local teacher to apply for federal funding to start a summer meals site in Quitaque for local kids, to take some financial pressure off their parents.

Having lived in Quitaque most of her life, Calvert was ignorant of the depth of need in the community until she helped start the food pantry 13 years ago.

She fought back tears when she told the story of seeing a pair of young siblings cooking beans on the stove in a house otherwise empty of food. At another house, a volunteer for the pantry checked in on an elderly woman and found cat food in her fridge — and no cat in the house.

“I thought I knew our neighbors. I thought I knew everybody was OK,” she said. “Guess what? We don’t take care of our neighbors.”

Turkey-Quitaque ISD Superintendent Jackie Jenkins said the district stopped offering summer meals two years ago, around the same time it stopped hosting summer school for lack of funding. Before that, Jenkins drove a van taking kids home from summer school and bringing sandwiches and fruit to hungry kids who were not able to attend the summer classes. She knew parents were likely working in the fields and unable to drive kids even 10 miles to get lunch.

"We knew it would be hard for them to come out here, so we delivered them," Jenkins said. But the federal program that paid for the district's meal program didn't cover those transportation costs. Now the closest program is in Memphis, a town almost 50 miles to the northeast.

Local food pantry is a lifeline

It's not just students who need help getting fed. In Quitaque, where the tiny town center is surrounded by thousands of acres of red-dirt cotton fields, many residents are day laborers, cleaning homes and mowing yards in town or working on farms seasonally during the cotton harvest.

“There’s not enough work here in these small communities. But yet they want to raise their kids here because it’s the cheapest place they can live,” Calvert said. “They don’t want to go to the cities because they can’t survive in the cities.”

The local food pantry, Tri-County Meals, collaborates with the regional High Plains Food Bank to bring boxes of food each month to elderly people and families who are regularly deciding whether to pay for heat during the winter or buy groceries at the single store in town. The food bank trucks the food to an old fire station in Quitaque, and volunteers from three nearby towns haul it away for local distribution.

By noon, the floors and tables in the old station are piled high with boxes of all types of foods: organic baby spinach, bananas, croissants and other assorted breads, packages of Hamburger Helper (popular with the kids), giant frosted chocolate cakes.

The box of food Judy Myers and her brother Danny Barrett receive every month from the mobile food bank gets their family almost through the full 30 days. Myers, 55, a former prison employee, and Barrett, 57, a former mail carrier, both had to stop working because of chronic health problems. Myers has back and kidney issues; her brother suffers complications from diabetes.

They live together in a house that sits on 200 acres that's been in the family for nearly a century. Myers has about $1,700 in pension payments coming in each month, and they both are applying for disability benefits.

Last Christmas was “really black in our house,” Myers said, sitting on her back porch with two kittens napping at her feet. “We had nothing at the time to cook with.”

They got an emergency food delivery through Tri-County Meals. In January, when her daughter Breanna turned 12, Myers asked the food pantry for cupcakes so Breanna could hand them out to her classmates.

But during the summer, Breanna is home from school, and Myers babysits her 2-year-old grandson — two extra mouths to feed during the day. Myers said she wishes the school district was still giving out free food in the summer, to take some of the pressure off her wallet.

Local kindergarten and first-grade math teacher Shadi Buchanan is working with Calvert to re-start a summer meals program in Quitaque, applying for reimbursement from the federal government.

But first they need committed volunteers. Parents and teachers already serve several roles for the school district, transporting kids to sports practices or teaching four or five different grades of a subject, because the district can’t afford to hire additional employees.

“It takes us all to run this village, and I think sometimes it’s overwhelming to say, 'Here’s one more thing to do,'” she said.

Buchanan wants to run the program at two separate sites, one providing meals in Quitaque and the other in Turkey, so students don’t have to make the trek more than 10 miles to school for a free meal without a bus. Jenkins has her fingers crossed that enrollment will increase once school starts in late August since more students means more state money to spend on school programs.

In the meantime, Calvert and the rest of the team at the pantry will continue to serve as many families as possible, for as long as they have the money.

“They’re out there if we open our eyes and look. The need is out there,” Calvert said. “We can only do so much.”

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Aliyya_Swaby_TT.jpg)