As court scoldings pile up, will Texas face a voting rights reckoning?

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/61b48f55c90396dafdeb0a0cfa4353e6/BD%20INC%20Map%202011)

Lock the Vote

This is an occasional series about how Texas leaders choose their voters — using gerrymandering and voter ID laws — as courts repeatedly scold them for disproportionately burdening voters of color.

More in this seriesThis is the first story in an occasional series about how Texas lawmakers choose their voters — and limit voters' opportunities to choose them.

Nearly two hours into the House’s marathon budget debate this spring, a conversation about funding the state’s future U-turned toward the past. Triggering the about-face: the issue of redistricting, the once-a-decade process of redrawing political boundaries to address population changes.

State Rep. Chris Turner, D-Arlington, laid out an amendment seeking to bar Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s office from using more taxpayer money to defend a congressional map that a court had just declared unconstitutional — ruling that it was intentionally drawn to discriminate against minorities. Paxton's office had already spent millions of dollars on the case.

As he explained his amendment, Turner called Texas the “worst of the worst” voting rights violators.

The Republican-dominated chamber was destined to table the amendment, pushing it to a pile of Democrats’ other long-shot proposals. But first, Rep. Larry Phillips strolled to the front mic to defend his colleagues — past and present.

“I voted for those maps. I didn't intend to discriminate,” said Phillips, a veteran House Republican and a member of its redistricting committee in 2011. “I want the attorney general to still fight for those of us that felt like we were doing the right thing for Texas under the Constitution, under the law, and join me in showing that we did not discriminate."

Scattered applause echoed in the chamber. As Phillips turned toward his desk, Rep. Poncho Nevárez, a Democrat from Eagle Pass, stopped him with a pointed question from the back mic.

“Larry, do I have to bring the emails that the federal judge perused to come to a ruling so we can talk about what the intent was by the authors and the people working on the bill?” he asked, referring to emails revealed through a court case that pulled back the curtain on some redistricting deliberations.

A 90-55 vote to kill the amendment ended the tense moment on the House floor, but it could not mute the reverberations of 2011 — a session marked by emotional debates about voting laws that, in some ways, echoed those from the state's discriminatory past when "white primaries" and poll taxes aimed to block minorities from voting.

Six years later, a barrage of federal court rulings that the 2011 Legislature intentionally discriminated against people of color has forced Texas leaders to confront the possibility that they strayed too far in meddling with elections — and put the state at risk of once again having the federal government monitor its election laws. The cases could answer nationwide questions about the strength of the U.S. Voting Rights Act, just four years after part of it was gutted.

The wave of judicial scoldings washed over Texas lawmakers this spring:

- A San Antonio-based panel of judges flagged three of the state’s 36 congressional districts as illegally drawn, ruling that the Legislature “packed” and “cracked” certain populations to dilute minorities' political clout in a rushed redistricting process featuring “misleading information” and “secrecy.”

- Weeks later, the same judges found fault with the state House map, also drawn in 2011. The ruling said lawmakers intentionally undercut the voting strength of minorities statewide and in particular districts.

- Wedged between those decisions: U.S. District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos of Corpus Christi ruled — for the second time — that lawmakers purposely discriminated against Latino and black voters in passing Senate Bill 14, a voter photo identification law considered the nation’s strictest. That law, which Republicans claimed was needed to prevent voter fraud, required voters to present one of seven forms of photo ID at the polls, a narrow list of options that minorities were less likely to carry.

The court rulings, if they withstand appeals, could reinsert the federal government into crafting Texas election laws.

For decades under the Voting Rights Act, Texas was on a list of states and localities needing the federal government’s permission to change their election laws, a safeguard for minority voting rights called preclearance. The U.S. Supreme Court wiped clean the list in 2013 and lifted federal oversight for Texas and other jurisdictions, noting that conditions for minority voters had "dramatically improved."

But the ruling left open the possibility that future, purposeful discrimination could mean a return to preclearance. Now, minority rights groups and Democrats say the recent string of federal court rulings show the state has squandered its respite from federal oversight.

“Texas is at or near the top among jurisdictions who are at most risk of being put back under preclearance — if anybody is going to be,” said Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s adviser on constitutional literacy and former longtime reporter at SCOTUSblog. “The evidence is pretty strong in the Texas Legislature. The question is, is it strong enough for the majority on the Supreme Court?”

The state's Republican leadership — who have all played roles in the redistricting and voter ID fights — downplayed the rulings throughout most of this year's legislative session.

During his tenure as attorney general, Gov. Greg Abbott advised the Legislature and its map drawers and initially defended the state against lawsuits over the maps and the voter ID legislation. He has "no concerns whatsoever," his spokesman John Wittman told the Texas Tribune in early May. Wittman downplayed Abbott's advisory role in the redistricting process and accused Democrats of fueling the voting rights dispute with "phony cries of racism."

"That view can be traced back to trial lawyers whose trade it is to profit from fomenting racial tension, and is echoed by a handful of Democratic lawmakers seeking to undo legislative decisions they disagree with by turning to activist judges," Wittman added.

Despite loud calls from Democrats to try to fix the political maps during the legislative session, the Republican chair of the House Committee on Redistricting refused to call any hearings to discuss the rulings.

In late May, however, the near demise of legislation to soften the strict voter ID law set off Republican fears that inaction — specifically on that issue — would trigger a preclearance ruling. Lawmakers pushed Senate Bill 5 to the finish line only after Abbott declared it an emergency item hours before a bill-killing deadline.

Throughout that sprint, Republicans pushing the bill made clear they were focused more on placating Judge Ramos, rather than conceding errors from 2011.

“I know a court has ruled otherwise, but as someone who was here in 2011, I don’t believe there’s any evidence that we intended to discriminate,” Rep. Phil King, R-Weatherford, the bill’s House sponsor, said during a May floor debate. “We didn’t want anyone to be disenfranchised, we didn’t want any disparate impact — we just wanted to be pragmatic.”

According to Democrats, that legislation won’t go far enough to expand ballot access — or to save Texas from federal oversight. Revisions to the law don’t absolve the Legislature from any discriminatory sins, they’ve argued.

Texas Republicans may be banking on sympathy from the Supreme Court, where the redistricting and voter ID cases could eventually land. Convincing a majority on that body, which is sensitive to states' rights, to put Texas back under federal oversight won’t be easy, Denniston and other experts say.

The judges “are going to be very skeptical about any finding of discriminatory purpose or intent, and are going to insist on it being very current,” Denniston said. “It’s going to be a pretty uphill climb for civil rights groups.”

This is hardly Texas’ first voting rights battle in the courts. The state’s history is pockmarked by efforts to disenfranchise people of color.

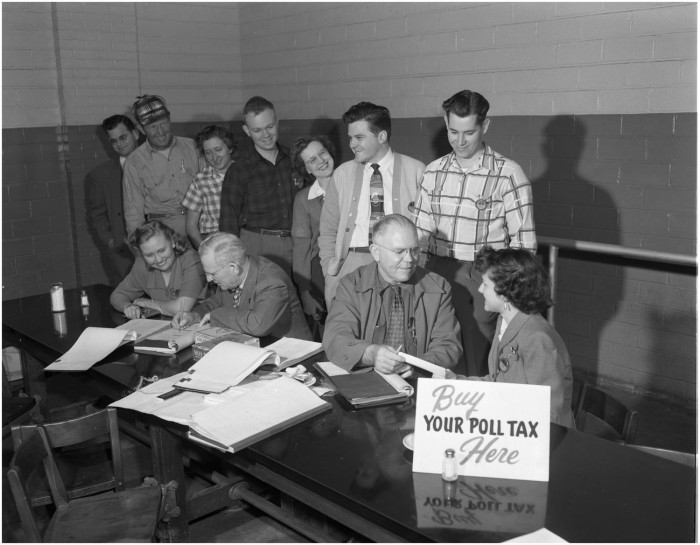

Following the Civil War, emancipated slaves in Texas enjoyed a brief stint of political access, even gaining black representation in the Legislature. But when Reconstruction ended, Texas and other southern states — led by the Democratic Party — used a variety of tools to exclude blacks and Latinos from the democratic process. They concocted "white primaries," charged "poll taxes," eliminated interpreters at the polls and barred people from helping illiterate folks cast their ballots.

At the same time, state leaders relied on brutality and intimidation — often carried out by the Ku Klux Klan or Texas Rangers — to scare Hispanic or Latino voters away from the polls.

Until the mid-1960s, state lawmakers used poll taxes to suppress turnout among minority voters, who were disproportionately poor. Then, as now, lawmakers claimed to be protecting the election process from voter fraud.

And when the courts and Congress advanced voting rights in the 1960s — invalidating poll taxes and enacting the Voting Rights Act — the Texas Legislature swiftly adopted a new law to discourage turnout: an annual re-registration requirement. Gov. John Connally, then a Democrat, called a special session in 1967 to adopt the measure, which he called the “most logical means of preventing fraud and guaranteeing the purity of the ballot box.”

Courts struck down that law in 1971, so the state enacted another law to purge voter rolls, effectively requiring the entire electorate to register again. The Department of Justice blocked that move with its preclearance powers, writing that a "substantial number of minority registrants may be confused" or only able to comply "with substantial difficulty."

The state has an equally troubled record when it comes to redrawing its political boundaries: Federal courts and the U.S. Supreme Court have been scolding the Texas Legislature for engaging in a pattern of racial discrimination in every redistricting cycle since 1970.

“Texas has an abysmal record when it comes to protecting the voting rights of minorities,” said former state Rep. Trey Martinez Fischer, a San Antonio Democrat who led the redistricting fight while in the House. “This happened under Democratic control. This happened under Republican control ... The only thing that’s really changed on this issue is the jersey.”

Dallas Rev. Peter Johnson, a longtime civil rights activist who once instructed minority voters on how to pass literacy tests designed to disenfranchise them, said modern electoral discrimination isn’t new — it’s just more subtle.

“There’s nobody that’s going to shoot at you if you register to vote today. They aren’t going to bomb your church. They aren’t going to get you fired from your job,” he said. “You don’t have those kinds of overt, mean-spirited behaviors today that we experienced years ago ... they pat you on the back, but there’s a knife in that pat.”

Now, following the Supreme Court's 2013 decision, any return to preclearance would hinge on the Legislature's most recent actions, rather than decades-old discrimination.

In the redistricting case, Democrats and minority groups say the strongest proof of intentional discrimination is in the emails made public during litigation.

"When somebody says, ‘Well how do you know that person was thinking about discrimination when they drew that map?’" Martinez Fischer said, "You can come back and say: Because if you look at the emails, it makes it very clear what their motive was.”

That's a reference, in part, to emails between a lawyer working with the GOP congressional delegation and a map drawer for House Speaker Joe Straus. They reveal discussions about manipulating Hispanic voter turnout using a “nudge factor” that would allow leaders to redraw a district around Hispanic Texans who were seen as unlikely to vote.

The emails also referenced “Optimal Hispanic Republican Voting Strength,” a measure of “how Hispanic, and Republican” certain census blocks were.

Plaintiffs in the redistricting case also pointed to software used that can split voting precincts along racial lines, which could allow officials to use race to shape boundaries at a block level — an area where granular data on political leanings is virtually unattainable.

The state’s map drawers deny that they predominantly used Hispanic turnout data, any sort of nudge factor or leaned on block-level racial breakdowns to draw districts. But the federal judges weighing the case have ruled that defense lacks credibility.

“I disagree with the court, obviously on the basis that it was intentional discrimination. There was nothing intentional about it," said former Rep. Burt Solomons, a Republican who chaired the House Committee on Redistricting in 2011. “You can look at the partisanship aspect of it and say, maybe that was a little too much.”

In the voter ID battle, the state's opponents criticized the Legislature for failing to consider the law's effect on minority voters. Faced with such questions on the chamber floor in 2011, Sen. Troy Fraser, the law’s Republican author, repeatedly answered: “I am not advised.”

In an April ruling, Ramos referenced Texas' long history of racial discrimination in elections and slammed the 2011 Legislature for its “virtually unprecedented radical departures from normal practices” in ramming the voter ID bill through the Legislature and lawmakers' “shifting rationales” for pushing it.

“There was no substance to the justifications offered for the draconian terms of SB 14,” she wrote.

Testimony in the case would later reveal that Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst knew of an early secretary of state analysis estimating 678,000 to 844,000 registered voters lacked ID required by the law. But no one released that data to the Legislature. (Experts later pegged the number at around 600,000, though not all of them necessarily tried to vote).

Floyd Carrier, a black Korean War veteran and a plaintiff in the case, was one of them. His Kafkaesque attempt to find an accurate birth certificate — required documentation for those trying to get a photo ID — derailed his attempt to vote in 2012. With his son’s help, Carrier contacted three counties in his birth certificate search, to no avail. He then paid the state $24 to retrieve it, only to receive a certificate riddled with errors, including misspellings — his first name on one document was spelled “Florida” — according to court filings.

After Carrier paid a $12 notary fee amend that certificate, the state sent him back another inaccurate document. Eventually, Carrier ran out of time to get photo ID, and his Veterans Administration card, which he had presented in previous elections, wouldn’t suffice at the polls.

“He couldn’t believe that after serving his country in the war, all the Social Security he’s paid working his entire life, he was denied the right to vote for a simple card,” Floyd’s son Calvin Carrier testified in court in 2014.

Throughout six years of litigation, the state’s lawyers have argued the ID law could not have denied voting rights to Carrier or other elderly Texans with similar stories. The lawyers point out some of those folks could have cast ballots by mail — no photo ID required.

Ramos rejected that argument, and so does Johnson. The civil rights activist said black Texans his age see their presence at the polls as a near-sacred way to exercise rights once denied to them.

“There’s a certain amount of dignity in that generation about going to stand in line and vote,” Johnson said.

As the court battles continue, Texas has emerged as one of few states that could spur a new era in federal electoral guardianship, and one of its cases could be the next big one to reach the Supreme Court. But first, lower courts must consider whether to slap the state with preclearance.

“The fact that multiple courts are making these findings make it much more likely that it’s not just one aberrant judge making this decision, but a pattern of a problem,” said Rick Hasen, a professor at the University of California, Irvine's law school who specializes in election law. “Everyone’s watching what happens in Texas.”

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Jim_1.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/ura-alexa_TT.jpg)