Rep. Dutton: If "raise the age" bill dies in Senate, I'll kill Senate bills

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2017/05/10/Harold_Dutton_May_10_MKC_TT.jpg)

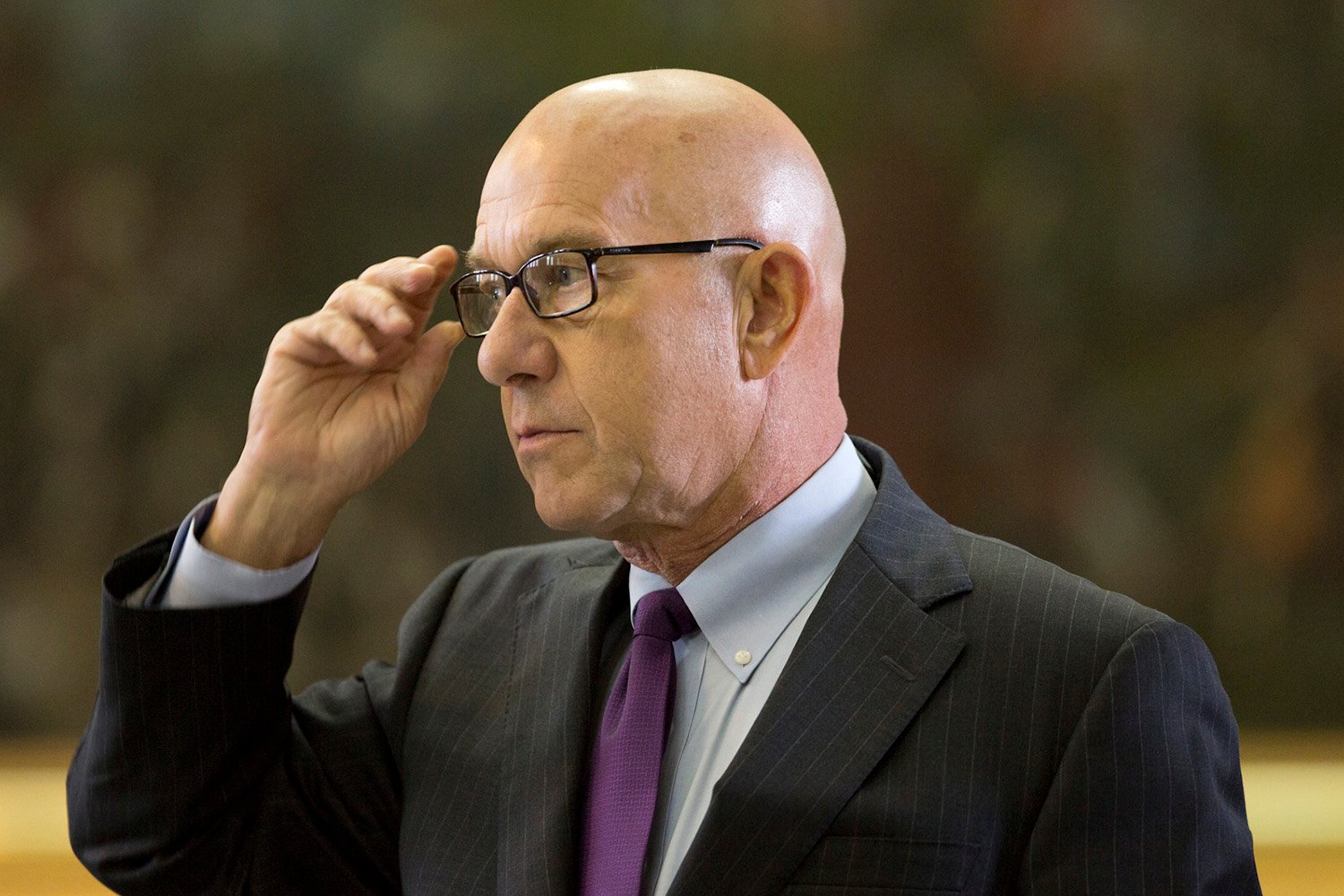

State Rep. Harold Dutton Jr., D-Houston, has set his crosshairs on Senate bills Wednesday after learning that a major criminal justice reform bill that he authored was not only languishing in the upper chamber but appeared to be left for dead.

House Bill 122, also known as the "raise the age" bill, would raise the age of criminal responsibility in Texas from 17 to 18, meaning people would be treated as adults in the criminal justice system only after turning 18. The House passed the bill in late April by a 92-52 vote, but the legislation has not moved in the Senate.

The bill's most vocal critic, state Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, has said the time isn't right to raise the age because questions linger about safety and how to pay for moving 17-year-olds into the juvenile justice system. Those questions have been answered many times, said Dutton, chairman of the House Juvenile Justice and Family Issues Committee.

"If House Bill 122 dies, it's going to be a big funeral, because a bunch of Senate bills are gonna die," he told the Tribune.

He launched his first salvo Wednesday morning, forcing all Senate bills off the day's local calendar in the House with a parliamentary maneuver.

Whitmire declined to comment on Dutton's "raise the age" bill Wednesday but later said killing any of his bills won't hurt him personally. He pointed to bills he has pending in the House, including a bail bond reform bill and another that would prevent crime victims and witnesses from being jailed to ensure they appear in court.

"If you stop a John Whitmire bill ... you're just hurting our people," said Whitmire, chairman of the Senate Criminal Justice Committee.

Dutton responded: "Why do we need [those bills] more than we need raise the age?"

Dutton and colleagues have put forward similar bills for years, only to see them fail despite numerous studies showing the benefits of raising the age of criminal responsibility. For about 100 years, Texas has treated 17-year-old offenders as adults in criminal matters, but Dutton said the 17-year-olds of a century ago, when life expectancy was shorter and people married much younger, are not the 17-year-olds of today.

"That bothered me," he said, "just that fact that it's been around for a long time."

Thousands of 17-year-olds go through the adult criminal justice system each year, mostly for misdemeanor offenses. Starting their adult lives with adult criminal records could effectively end them, Dutton said.

"That's why we put the juvenile code over in the family code and not [in] the penal code," he said.

Research also shows that 17-year-olds are less likely to commit new crimes if they are rehabilitated instead of being locked away in the adult system.

Before Dutton's bill passed in the House, state Rep. James White, R-Hillister, offered an amendment that would delay its implementation until 2021, which he said would give state leaders more time to sort out the details.

White, the chairman of the House Corrections Committee, said there's only one thing that matters at this point: "At the end of the day, the question is, will there be better outcomes for 17-year-olds if we raise the age?"

White offered an answer to opponents' safety concerns: If someone under 18 has "done something heinous," prosecutors can still certify them as adults in court.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/silver-johnathan.jpg)