Will Senate bill provide tax relief or hamstring local governments?

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2015/02/24/PropertyTax-DollarSigns.jpg)

Editor's note: This story has been updated.

A Texas Senate bill taking aim at how much property taxes local governments can collect without voter approval will either offer Texans much-needed relief from rising tax bills or create public safety crises in cities across the state.

Like so many of the local control battles playing out in this year’s Legislative session, the likely result all depends on whom you ask.

State Sen. Paul Bettencourt’s Senate Bill 2 promises to limit when local governments like cities, counties and school districts can collect more property taxes without getting voter approval. It would also change the makeup of many of the boards that oversee appraisal districts that determine property values and the panels that decide landowners’ appeals of appraisals.

The Senate Finance committee began discussing the bill shortly after 9 a.m. Tuesday in Austin. Bettencourt, a Houston Republican, filed SB 2 after holding a series of meetings about property taxes across the state in which he said Texans repeatedly complained about tax bills jumping dramatically. State Rep. Dennis Bonnen, R-Angleton, has filed a similar bill in the House, but a hearing hasn't yet been set.

“We don’t want to tax people out of their homes or their businesses,” Bettencourt said.

A University of Texas/Texas Tribune poll last month found that lowering property taxes was Texans’ overall top choice on a list of a possible legislative priorities. Bettencourt filed a similar bill last year, but it never made it out of committee.

The new bill has plenty of opposition from local government officials who say it would hamstring them from funding necessary services without providing much actual relief to everyday Texans. And the bill sidesteps a fix to the state’s school financing formula, which they stress makes up the bulk of local property taxes.

“The hidden tax is the state’s over-reliance on property taxes to fund schools,” said Bennett Sandlin, executive director of the Texas Municipal League, an advocacy group. “If we fix that problem that would be real, meaningful tax relief.”

Because Texas has no income tax, it relies heavily on sales and property taxes. The state and local entities split sales taxes. But only local entities receive property taxes. It’s unconstitutional for the state to levy property taxes and state lawmakers don’t have the power to set those rates.

But there are provisions in state law guiding how and when local governments can raise property taxes. Right now, an 8-percent property tax increase or higher allows voters to gather signatures to call for an election on the new rate. Bettencourt’s bill would lower that threshold to 4 percent and would require an automatic election.

Both the current and proposed thresholds are calculated via arcane mathematical formulas with which many Texans may not be familiar. Long story short: It’s not based on a pure increase in an individual landowner's tax bill.

Instead, the formulas are based largely on the collective amount of money a taxing entity is set to receive from the properties in its jurisdiction compared to the amount it received from those same properties last year. Under Bettencourt's bill, a local entity triggers an automatic election when it tries to increase the overall tax revenues it brings in by 4 percent (with some adjustments made for lost property and new land coming onto tax rolls).

But the election threshold figure doesn’t just focus on the actual tax rate, which is the amount per $100 of property value that a government entity levies against landowners. In fact, a taxing entity could trigger an election even if the actual tax rate it levies on all properties remains flat.

That’s because property values – the amount that land and the structures on it are worth – play a major role in determining how much a taxing entity brings in. If the values of properties within that government entity go up significantly, which has been the case in parts of Texas in recent years, it could hit the rollback rate even if it doesn’t change the actual tax rate.

Bettencourt said that in the meetings he held last year around the state, Texans’ top complaint was that their local governments didn’t account for rising values when setting tax rates.

“As values went up, tax rates didn’t come down,” he said.

Fort Worth Mayor Betsy Price takes issue with that statement. Her city lowered its tax rate 2 cents last year as property values rose. She still opposes the bill, though, because she said it will prevent city councils from properly responding to different economic cycles and growth patterns.

“We need the flexibility,” she said.

Houston voters more than a decade ago capped how much that City Council could increase taxes. Mayor Sylvester Turner said that has limited the financial resources he has to fill potholes, add parks and put infrastructure in place for expected growth.

“We’re not talking about raising the taxes,” he said. “We’re talking about the cost of the growth of our city.”

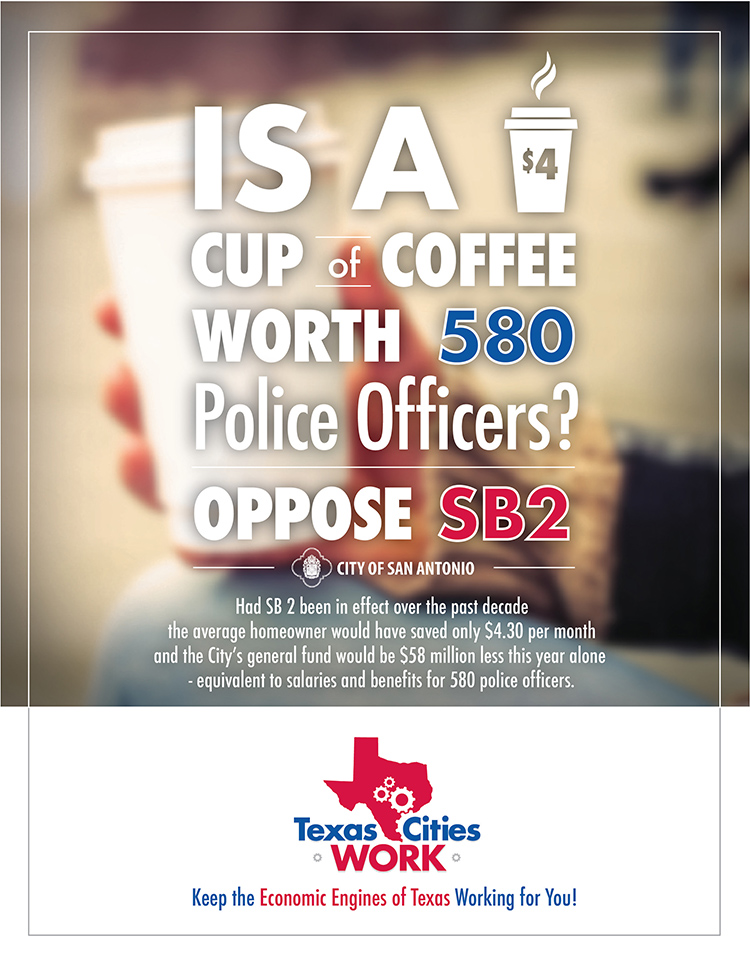

The City of San Antonio on Monday sent out an email opposing the bill. The city said that had the bill been effect for the past decade, the average homeowner would have saved $4.30 a month, but the city this year would have forgone $58 million, the equivalent of salaries and benefits for hundreds of police officers.

“Is a $4 cup of coffee worth 580 police officers?” the city asked in its email.

Supporters of the bill take issue with such arguments.

“It’s an interesting message because what these same local officials are saying is that we don’t fund critical services first,” said Daniel Gonzalez, legislative affairs director for the Texas Association of Realtors.

Disclosure: The Texas Municipal League and the Texas Association of Realtors have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors is available here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Brandon_Formby_2x3.jpg)