Texas counties rally against statewide court records portal

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2016/08/03/OpenRecordsRequests.jpg)

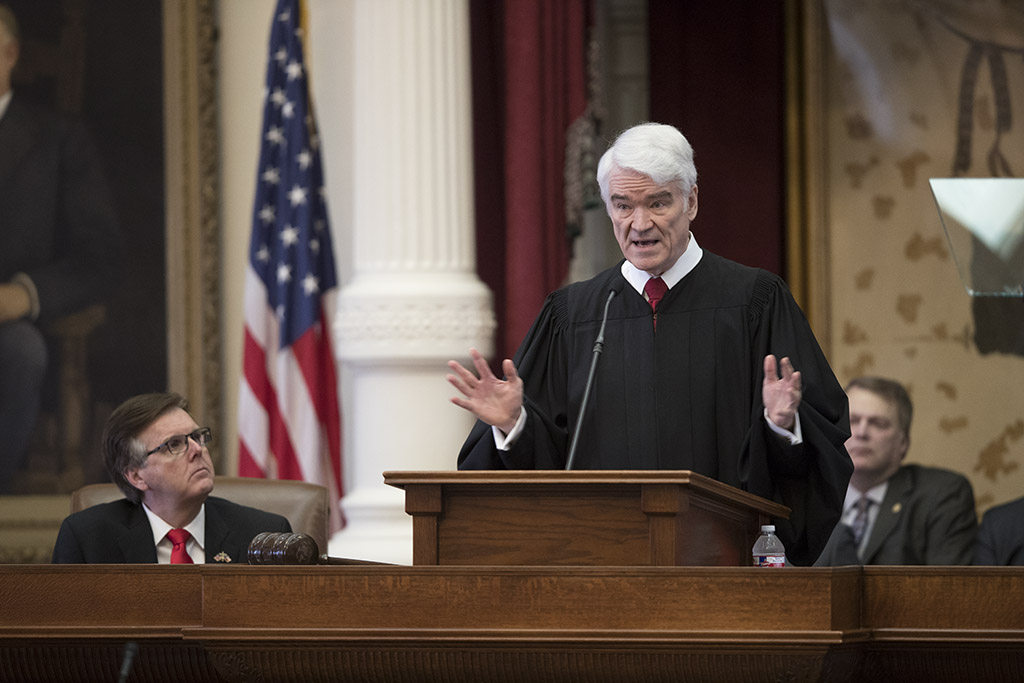

Nathan Hecht, chief justice of the Texas Supreme Court, has noticed a curious trend in the state’s legal system: Folks are increasingly representing themselves in legal disputes, forgoing lawyers altogether.

“They really need legal help, but they don’t feel like they can afford it,” Hecht said.

But ditching a lawyer doesn’t make justice free. Obtaining legal records can be a big hurdle — time away from work, trips to a courthouse that may be far from home and copying fees that can run a dollar per page for documents that often run hundreds of pages.

“We’re talking about tens of thousands of people for whom getting a court record is probably impossible, at least practically,” said Hecht, who has long sought to help poor Texans navigate the legal system.

That’s just one reason he’s excited about efforts to deliver court records from all 254 counties to Texans’ fingertips through an online portal. Some urban counties — Dallas, Harris, Travis and Tarrant, for instance — individually put their records online. But scores of other counties rely only on old-fashioned paper, necessitating trips to the courthouse and making statewide research next to impossible.

The Texas Supreme Court, through its Office of Court Administration, has worked for years on a one-stop legal records shop. Called re:SearchTX, the project is coming out in phases, with plans to eventually provide widespread public access.

The Office of Court Administration last September extended a contract with Tyler Technologies, a Plano-based company that already has integrated every Texas county into a filing system allowing attorneys to electronically send documents to the clerks. Under that four-year $72 million extension, Tyler would keep that system running through 2021 and eventually open it to the public.

The public portal would be funded through fees that attorneys pay to use the system. It would function like PACER, a widely used federal portal that charges subscribers small fees for access.

“It’s just crucial,” Hecht said. “It’s important for transparency. The media and the public at large have a very fundamental interest in the public justice system.”

But county and district clerks are fuming. They’re pushing to kill the project in a wonky battle involving local control and privacy concerns, multimillion-dollar contracts and confusion about how the portal would ultimately work.

“Clerks have been doing this forever,” Tarrant County District Clerk Tom Wilder said last week at rollicking meeting of the Judicial Committee on Information Technology, which advises the state Supreme Court. “It’s a duplication of effort.”

If the records get breached, he later told a reporter, “it’s our ass.”

At least 168 counties have adopted resolutions opposing re:SearchTX. They’ve found friendly ears in a Legislature that often shrugs off arguments for more local control on other issues, such as oil and gas drilling and penalizing polluters.

Rep. Travis Clardy, R-Nacogdoches, has authored a bill that would kill the data project — or at least indefinitely pause it — by requiring approvals from every county before it moves forward.

House Bill 1258 would “protect the constitutional rights and duties of the clerks,” Clardy, a trial lawyer in his day job, said in an interview. He suggested re:SearchTX faced “a bunch of open-ended, unsolved, logistical technical problems.”

Thirty-nine House members in both parties have signed onto his bill.

The database “does not serve the taxpayers of Texas,” he told the House Committee on Judiciary and Civil Jurisprudence, which left the bill pending Tuesday after a lengthy discussion.

But killing re:SearchTX would ultimately waste millions of dollars already committed to the project, its planners say.

About 200 Texas judges can already see statewide records through re:SearchTX. The Supreme Court’s tech advisory group is drawing up recommendations for broader access — first for licensed attorneys, and then the wider public. Current plans wouldn’t fully open the system for months, if not more than a year, as developers work out any kinks.

If lawmakers pull the plug?

“We’d still have to pay [Tyler] the same amount,” said David Slayton, administrative director of the Office of Court Administration. “We just wouldn’t get the services for that.”

County clerks say they fear a variety of potential complications. What if particularly sensitive documents, such as sealed information about kids or expunged criminal records, somehow end up online? Clerks also suggest they may need to buy expensive software to occasionally redact social security numbers or other private information in documents.

“If re:SearchTX is a great idea, counties should have the opportunity to opt-in,” Parker County District Clerk Sharena Gilliland told lawmakers Tuesday.

The project’s backers say the clerks don’t seem to completely grasp how the system would operate, and administrators promise not to flip the public switch until after they fully address any privacy concerns.

Lisa Hobbs, an Austin-based appellate lawyer and former Texas Supreme Court general counsel, told the judiciary committee that it was funny to hear worries that re:SearchTX was moving too fast, considering that PACER’s federal portal began in 1988, when subscribers could summon the data on terminals in libraries and office buildings.

“We are way far behind the ball here,” Hobbs said.

It's unclear whether re:SearchTX would mean more or less revenue for counties.

Counties might make less money on copying fees, but they would divvy up all of the revenue from subscribers. The Supreme Court’s advisory body has yet to recommend a price scheme, but one informal proposal would charge users 10 cents a page and up to $6 per document. (PACER charges the same per page with a $3 cap.)

The database would almost certainly threaten the bottom line of a firm called iDocket, which contracts with 149 Texas county and district clerks in Texas, about two dozen of whom put all their documents online.

The firm sells that data, charging some subscribers hundreds of dollars per month, depending on the plan. Counties get a 20 percent cut, said Chris Moreno, an iDocket programmer who testified in support of Clardy’s bill Tuesday.

Moreno told the committee that only her company knows how to meet the clerks’ needs.

For his part, Hecht doesn’t dispute that clerks have authority over public records, “but they’re arguing for restrictions – keeping people from records,” he said. “I’m hopeful that misinformation will be dispelled.”

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Jim_1.jpg)