/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2016/10/06/MHN_TT_ES_52.jpg)

SAN SALVADOR — Forensic anthropologist Saul Quijada stands in a refrigerated room where cardboard boxes stuffed with bones fill the metal shelves from floor to ceiling.

The smell isn’t as bad in here as outside in the big room, where all the decaying human remains lie out in the open.

This room is where the bones that nobody has claimed end up — the last stop before an anonymous burial no loved one will attend. The bodies were dumped years, or even decades, ago in clandestine graves across the country, testament to the human toll that civil war and rival street gangs have wreaked in tiny, murderous El Salvador.

Most of the cardboard containers on the shelves look like bankers boxes, but the first one Quijada reaches for is a quarter that size. The clinical tone of his voice belies what he is about to pull out of it.

“Here we have one of our youngest people who is with us,” Quijada says. “We can see that this is the skull of a baby.” The head of the baby — believed to be a six- to eight-month-old boy, is barely larger than his fist. He puts it back in the box and pulls out a green jersey, which was found alongside the body.

After five years, nobody has claimed the baby’s bones. Sometimes even when bodies are identified, no one comes to collect them because family members fear they will be identified by their loved ones’ killers and become victims themselves.

“That is a little sad — to have remains that can’t be returned to families because no one wants to take them,” he says. It is sadder still — and somewhat uncommon, he says — that a baby boy’s remains have been sitting on a morgue shelf, unclaimed, longer than he lived.

With so many skeletons arriving every month, the unclaimed toddler will join the others in an anonymous burial in a local cemetery. Due to space limitations, five years is the maximum time the morgue can hang on to the remains. And Quijada says 20 more skeletons will soon be ready for examination.

“We’re running out of room,” he tells his visitors. “Sooner or later, we’re going to need to expand.”

The age of some of the bones brought here for testing underscores how long El Salvador, which lost an estimated 75,000 people in a 12-year civil war that ended in 1992, has been reeling from violence.

On the left side of one aisle are dozens of bone boxes stacked up from last year — when gang violence made El Salvador the murder capital of the world. On the right side, there is a sign taped to the top shelf that says “Mozote.” El Mozote is the name of the tiny town in northern El Salvador where, in December of 1981, soldiers massacred more than 800 civilians, many of them women and children. These bones, in boxes with codes describing their location and condition, were brought here from the village last year.

“We’re still receiving remains from there. And we will continue to receive them,” Quijada says.

Quijada oversees the Department of Forensic Anthropology, which handles the toughest cases — the skeletons and decomposed bodies found in abandoned fields, along river banks and in hastily dug graves. Fresh bodies arrive too, of course. But they are handled by the Department of Pathology, closer to the entrance of the modern-looking morgue in downtown El Salvador.

Last year the central morgue declared a state of emergency as bloody turf wars between members of the Mara Salvatrucha and Barrio 18 street gangs pushed El Salvador’s murder rate into the stratosphere. But in Quijada's Department of Forensic Anthropology, business has remained steady.

Even after a controversial truce between the two main gangs cut the official murder rate almost in half, disappearances in the country went up — and along with that came the discovery of new clandestine graves where bodies were being dumped. They’re still being discovered.

Often the victims are killed and then dismembered — with everything from homemade axes to powerful chainsaws — so they’ll fit into narrow, quickly dug graves. Other times dismemberment is part of the killing ritual.

“A lot of the dismemberments, they have multiple wounds all over their body where it’s not just a quick cutting off of the head,” says Munisha Kailley, a consultant from Canada who works at the morgue as a forensic archeologist. “Sometimes they are stabbed a lot of times. They’re hacking off their limbs, so it’s a little bit of a slower death.”

In one recent case the burial itself — where the pants of a male victim were wrapped around his ankles — demonstrated the torture-crazed mindset of the killers.

“The way the body was positioned was with the posterior up so that is for shame,” Kailley says. “You’re thrown into a grave with your hands tied up, with your posterior up, and your pants above.”

When skeletal remains arrive here, workers strip any remaining flesh and cartilage left on the bones and sanitize what’s left. The process doesn’t remove all the smell, though.

The pungent odor — a mix of rotting bones and antiseptic — permeates every inch of the main examination room. On any given day, forensic anthropologists are busy taking DNA samples, examining wounds and generally trying to determine how and why the person died.

The skeletons are spread out on nine examining tables, most nothing more than wooden planks sitting atop sawhorses. The victims are young and old, male and female, gang members and innocent bystanders. Nearly all died violently, officials say.

Jimena Reyes, a criminal psychologist who graduated from Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, studies the intentions behind violent crime in her native El Salvador. She says her work at the morgue has opened her eyes to the cruelty gang members inflict on each other.

Dressed in blue scrubs, Reyes calls the level of violence here “ridiculous.” Then she moves her hand in a chopping motion as she conjures up the worst case she’s experienced to date.

“I mean, I’ve seen remains with 197 traumas,” she says. “Not even as a criminal psychologist ... I can’t understand, like, the motivations behind it. How can there be so much violence? So much hate? So much passion to kill someone like that?”

On one table lie the remains of a teenager authorities believed was abducted last year at a shopping mall, then chopped in the face several times with a machete by members of the Barrio 18 gang.

So fierce were the blows it nearly decapitated the 15-year-old victim. He was targeted, investigators believe, because he was related to a government prosecutor. He was found in a field in gang-infested Tonacatepeque, just northeast of San Salvador. A hand wound indicates he tried to shield himself from the attack.

Across the aisle two skeletons lie next to each other, believed to be a husband and wife, dismembered by a machete. Another skull on a table nearby has a big piece missing on the top. At least two dozen tiny triangular puncture wounds can be seen on what’s left of it.

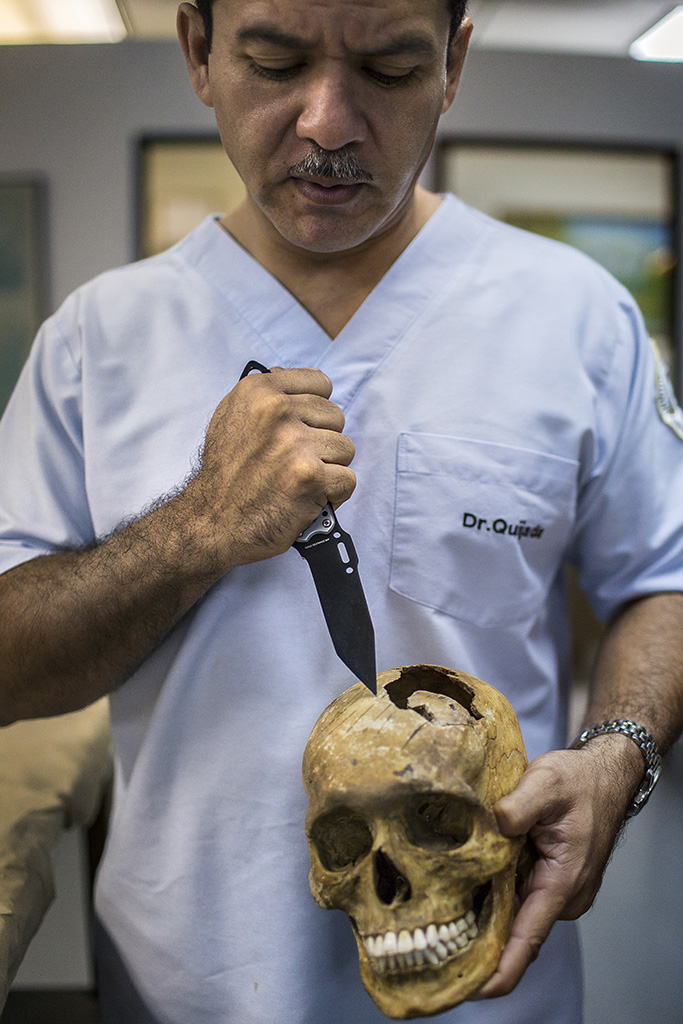

Asked how the victim died, Quijada retrieves a large knife from his office and demonstrates what he thinks happened. He cradles the skull in the crook of his elbow in an imaginary headlock, stabbing with the knife.

“There were so many repetitive blows that they fractured the skull and fragments were taken out,” he says. “We can see a lot of fury. We see a strong emotional factor here.”

It’s impossible to know the exact circumstances through a forensic examination, but Quijada said torture and mutilation often come into play when someone is killed for betraying or snitching on the gang or its leaders. Drugs and alcohol can also amp up the intensity of gang-related homicide.

To perform their work with professionalism and objectivity, Quijada says he and his colleagues have to separate their own emotions from their daily forensic tasks — all the while remembering that they’re dealing with “someone’s father, son, mother, family member or friend.”

Working with cadavers, however, isn’t the hardest part of the job. That comes on the days when they return remains to family members whose loved ones disappeared months or even years earlier. Sometimes they return as many as three or four bodies in a single day.

“When we are able to identify someone and return their remains to the family, it’s a very powerful moment. This day is charged with emotion,” he says. “Sometimes people faint. They cry. Other times they hug us as if we were returning their family members to them alive.”

Reyes, the forensic psychologist, said her interactions with family members have helped her understand better why tens of thousands of people — many of them children — are fleeing this country and crossing the U.S. border illegally.

“I’ve seen the fear in them. Like, I understand completely why they would want to leave,” she says. “There is fear that going home, if their kids refuse to join the gangs, then they’re threatened, and like three days later they disappear just because they didn’t want to join. So I can’t judge them for wanting to leave.”

This story is part of The Texas Tribune's yearlong Bordering on Insecurity project.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Jay_at_Cloak_TT.jpg)