Analysis: High Voter Registration Figures Are Great — Sometimes

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2016/02/25/6F6A9161.jpg)

Editor's note: If you'd like an email notice whenever we publish Ross Ramsey's column, click here.

Someone in our office has a friend who registered to vote for the first time this year but doesn’t plan to cast a ballot. Her explanation? “I just wanted to register to let them know I’m here.”

Here’s a pro tip: To the people on the ballot, you’re not here unless you vote.

The state’s top election officer — Secretary of State Carlos Cascos — has been pushing voter registration and, with some fits and starts, the best path through the state’s voter identification obstacle course.

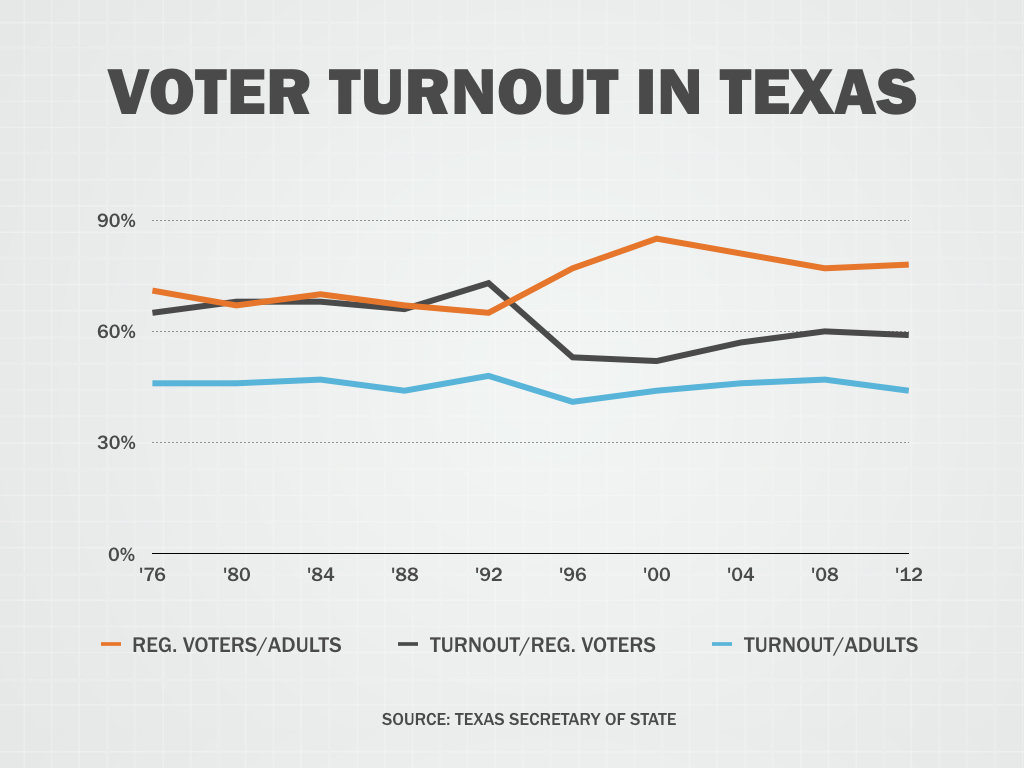

Voter registration, however healthy it might be, isn’t a good indicator of voter turnout. It has varied widely in presidential elections over the last 40 years in Texas, and as you might expect, voter turnout — as a percentage of registered voters — has varied widely, too.

Turnout isn’t nearly as volatile as registration. Over the past 10 presidential elections in Texas, the percentage of Texas adults registered to vote has gone as low as 65.3 percent in 1992 to as high as 85.4 percent in 2000.

The registered voter numbers have a problem, though. At any given time, some number of the people who have registered in Texas have moved or died. Election officials purge the rolls from time to time to correct for that, but using registered voters as a base for turnout calculations is messy.

The voting-age population, on the other hand, is based on population estimates. It starts with a census and changes with births and deaths — or, to be more accurate, deaths and the numbers of people turning 18 each year.

Using that number instead of registrations, Texans appear to be much more consistent in their voting turnout: 41 percent of Texas adults voted in 1996, the low year, and 47.6 percent showed up in 1984 and 1992, the two years with the best turnout over the past 10 presidential elections.

Those numbers don’t sync very well. If you’re measuring turnout by counting the number of actual voters among people on the registered voter rolls, you’ll get a relatively high number — and one that’s as volatile as the state’s database of registered voters.

If you measure it by comparing the number of adults in the state with the number of actual voters, you’ll get a more predictable result. More than four — and fewer than five — of every 10 adults has voted in each of the past 10 presidential runs.

You can run the voter rolls up with an active registration push, but it doesn’t necessarily mean turnout will improve.

In Texas, the biggest turnout years had attractive battles on the ballot. In 1992, Arkansas Democrat Bill Clinton was challenging Texan George H.W. Bush with Texan Ross Perot running a disruptive third-party race. That’s a lot of points of interest for Texas voters.

In 1984, Republican President Ronald Reagan — with Bush as his veep — was running the “morning in America” re-election campaign, firmly cementing a conservative stamp that has remained strong in Texas ever since.

You can run the voter rolls up with an active registration push, but it doesn’t necessarily mean turnout will improve.

On the other hand, the percentage of adults registered to vote rose to 77 percent in 1996 — almost 12 percentage points higher than in 1992. But turnout that year hit a low point, even with the increased registrations. Only 41 percent of adult Texans voted; only 53.2 percent of the registered voters cast ballots. Registration was way up, but turnout was down.

Registration rates fell in 2004, but voter turnout was up — another case where the two numbers had little to do with each other.

This part of the pitch for voter registration is correct: You cannot vote if you do not register. (The deadline this year is Tuesday, Oct. 11.)

That newly registered voter at the top of this column had that part right. She has a right to vote. She is now registered to exercise that right. But that doesn’t make her a voter, and nonvoters don’t matter on Election Day.

More columns from Ross Ramsey:

- The end of one political race is often the beginning of the next one. As former Gov. Rick Perry learned, an "oops" moment in one contest can color voter opinion in the next one. That ought to worry U.S. Sen. Ted Cruz.

- The Texas Legislature has become the court of last resort for companies and industries fighting local regulations in the state's cities and counties. And for those interests, Austin can be a very favorable venue for appeals.

- Voters in the state's largest school district can say no to sending money to other school districts, putting Texas lawmakers in a bind and — maybe — raising their own school taxes in the process.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/ramsey-ross_TT.jpg)