Texas Found 276 New Cases of Groundwater Contamination Last Year

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/WaterFaucetPouring.jpg)

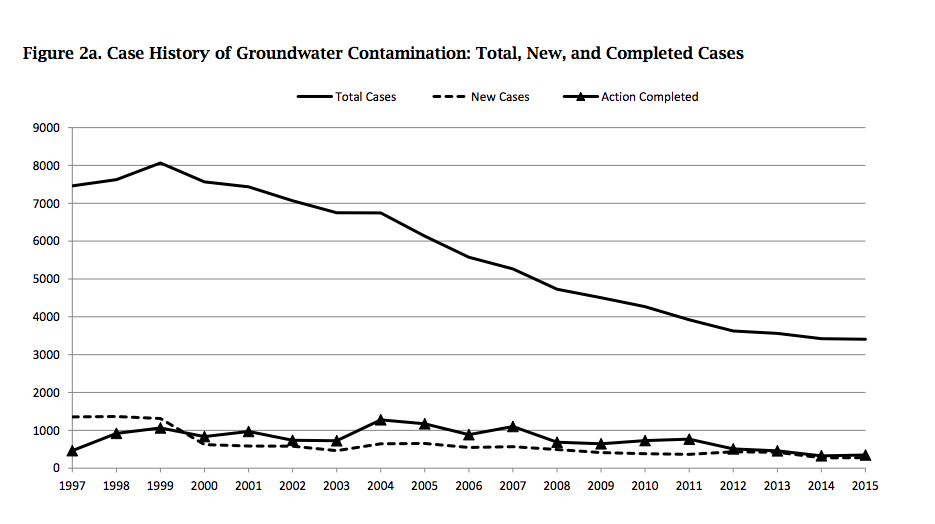

State regulators last year documented 276 new cases of groundwater contamination across Texas, a slight increase compared to 2014 but far fewer than in years past.

That’s according to the annual “Joint Groundwater Monitoring and Contamination Report” published last week by the Texas Groundwater Projection Committee, a collection of nine state agencies and a groundwater district group.

The committee's report offers a comprehensive look at fouled groundwater in Texas, a state that taps the resource for roughly 60 percent of its water needs.

New pollution cases in 2015 eclipsed the tally from the previous year, when regulators recorded 272 instances. But the number sat far below any other year during past two decades.

The long-term trend reflects the “maturing” of Texas Commission on Environmental Quality regulatory programs, the report stated.

Last year’s contamination came from many sources, including gas stations, laundry and dry cleaning services, chemical manufacturers and oil and gas drillers.

Though the types pollutants varied, gasoline, diesel and petroleum products were most common. “This reflects the large number of contamination sites (33.7 percent of the documented cases) reported by the TCEQ’s Petroleum Storage Tank Program,” the analysis said.

Among the report's other highlights:

- Twenty-three cases last year prompted the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to notify private well owners that their drinking water might be contaminated. Seventeen triggered notifications to local officials.

- State regulators in 2015 were dealing with more than 3,400 total groundwater contamination cases in some capacity — mostly those first documented years ago. This number has plunged each year since 2000.

- More than one-third of the total contamination cases were still under investigation last year, and regulators had planned or implemented “corrective action” in nearly 900 others.

- Oil and gas activities accounted for 50 new cases of contamination — two more than in 2014, even as a drilling slowdown continued. Common pollutants in those instances included chloride, BTEX (an acronym that stands for benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylenes) and mixtures of hydrocarbons found in crude oil. Overall, the Texas Railroad Commission’s oil and gas division is dealing with 570 contamination cases in 124 counties.

Gaye McElwain, a spokeswoman for the Railroad Commission, said the tally of contamination cases from oil and gas activities “is not analyzed for the purpose of evaluating trends, and each year is unique.”

Harris County led the state in ongoing oil and gas-related contamination cases (37) — those tracked by the Railroad Commission. Kleberg County was a close second (30), followed by Nueces and Brooks Counties (each with 21) and San Patricio (15), according to a map included in the report.

Harris County, home to the nation’s largest petrochemical complex, was also grappling with far more groundwater contamination cases reported to the TCEQ (671) than any other Texas county. Dallas County (296), Tarrant County (176), Bexar County and Travis County (54) rounded out the top five, according to the report.

Here is a look at Texas' documented contamination cases over nearly two decades:

Read more about water contamination in Texas:

-

Texas regulators have allowed energy companies in recent years to inject toxic materials into at least a “handful” of underground sources of drinking water, records show.

-

Tens of thousands of Texans live in places where the drinking water contains toxic levels of arsenic — a known carcinogen — and the state isn’t doing enough to discourage them from consuming it, according to a report from an environmental group.

-

The discovery of dangerous bacteria in the drinking water of two working-class communities along the Rio Grande set off alarms among state regulators and investigators. Since then, it appears that efforts to hold anyone responsible are sputtering to an inconclusive end.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Jim_1.jpg)