How a Decade in Texas Changed Elizabeth Warren

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2016/07/12/Warren-001.JPG)

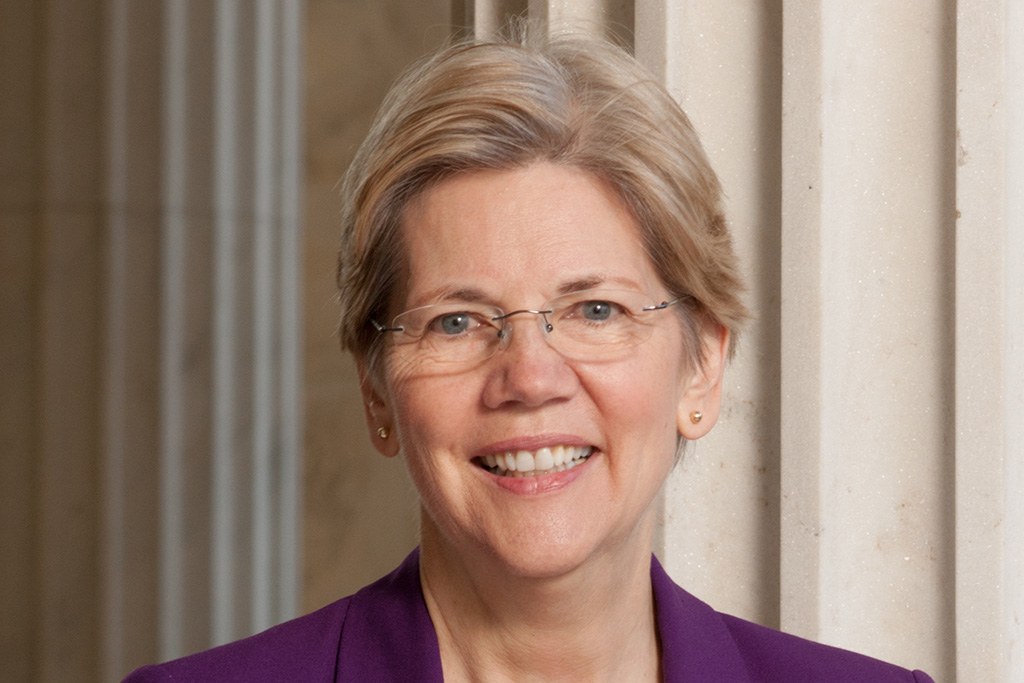

Two weeks before the Democratic National Convention, U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts sits near the top of pundits’ lists of possible running mates for Hillary Clinton.

Yet whether she is tapped to run with Clinton or just serve as one of the campaign's go-to surrogates, Warren is likely to spend much of the fall imparting to voters across the country a worldview that was largely forged in Texas.

The centerpiece of Warren’s political identity — that middle-class Americans are routinely harmed by policies designed to benefit big banks and the very wealthy — is rooted in the research she did at the University of Texas at Austin School of Law in the 1980s. In interviews with over a dozen former colleagues and students at UT and the University of Houston, a portrait emerges of an ambitious young scholar, known as Liz to her fellow professors, whose worldview was still taking shape as she made a name for herself in the field of bankruptcy law.

"You were having this view into people’s lives who were in really desperate trouble,” said Jay Westbrook, of the research he conducted with Warren 30 years ago at UT. “It changed our understanding of what the world is like.”

At an appearance last month with Clinton in Ohio, Warren delivered just the sort of fiery speech that has become her trademark, targeting outrage at Wall Street bankers and sympathy toward the struggling middle class. America, she said, is “angry that too many times Washington works for those at the top and leaves everyone else behind.”

Though she is now one of the most prominent liberals in the country, when she lived in Texas, Westbrook said he believes Warren viewed herself as a Republican. A spokesman for Warren declined to comment on whether she voted in any Texas Republican primaries in the 1980s, and in an interview with the Boston Globe in 2012, Warren would not say whether she voted for Ronald Reagan in the presidential elections of 1980 and 1984.

Warren's colleagues from that period say that while she was always interested in policy, she was not overtly political and that her early research was influenced by the Law and Economics movement, whose most famous adherents were rigidly pro-free market.

By the time she left Texas in 1987 to take a job at the University of Pennsylvania, Warren's focus had shifted considerably toward how the law could both encourage economic inequality and harm consumers.

Warren arrived at UT in 1983 as something of an anomaly. She was one of a handful of women on a faculty of dozens, and one of the few faculty members who earned her degree at a school that was distinctly non-prestigious: Rutgers School of Law-Newark, from which Warren graduated in 1976.

“I think she overcame a real bias,” said Calvin Johnson, a UT professor of corporate and business law who joined the school's faculty in 1981. “The bias was not woman. The bias was class. [Rutgers] is a former night school sitting in ugly downtown Newark. And way down on the pecking order.”

Warren has written that she came to the law almost by accident, after considering engineering and grade school teaching.

Warren had earned her bachelor's degree in speech pathology and audiology from the University of Houston in 1970, when she briefly lived in the city with her first husband, Jim Warren.

In 1978, after a stint in New Jersey where she got her law degree, the Warrens returned to Houston for Jim Warren's job at IBM. Warren landed a full-time tenure track position at UH as an assistant professor of law, where she earned a reputation as a well-liked teacher and energetic researcher.

She soon caught the attention of UT, who hired her as a visiting professor in 1981 and then as a full professor in 1983. It was at UT that she began her career-defining work on consumer finance issues, and developed the empirical methods that would characterize her scholarship.

Warren has said that she volunteered to teach bankruptcy law in her first semester as a full professor at UT on a whim. Her previous scholarship had focused on regulated industries.

“My curiosity got the better of me, so before we moved to Austin, I called the dean at the University of Texas and offered to teach a course I’d never taught before: bankruptcy,” Warren wrote in her 2014 memoir "Fighting Chance." She was curious at the time about who was going bankrupt and why.

As she further explored the topic, Warren realized the federal government collected little data about consumer bankruptcy. No one in academia or government could provide basic information like the financial situations of the people who filed for bankruptcy or how much debt was discharged through the process.

Warren concluded that Congress had been making policy with little understanding of how it might play out in the American economy. As a visiting professor at UT during the 1981-1982 school year, she met Westbrook, a law professor who had already done work on bankruptcy, and Teresa Sullivan, a sociologist who had published research on American workers and directed UT’s Population Research Center.

Together, the trio launched the Consumer Bankruptcy Project, the largest empirical study of bankruptcy then undertaken. From 1982 to 1985, they collected a quarter-million data points from 2,400 people in bankruptcy in Illinois, Pennsylvania and Texas.

On each trip, Westbrook said, they took with them a Xerox machine that required its own seat on airplanes. The machine, dubbed R2D2, was used to copy thousands of pages of public records as the researchers sat in the courthouse lobby or, if they were lucky, a discreet and quiet closet.

The project was a risky career bet. At the time, consumer bankruptcy was not a popular topic for either legal scholars or sociologists. When they started, Westbrook said, they were like “Lewis and Clark out there in the wilderness, trying to find out where the bears are at.”

And the method — time-consuming, painstaking data collection — was particularly unusual in the legal field, which favored theory. With the project, she and Westbrook aligned themselves with the empirical camp of legal scholarship, whose practitioners seek to explain the law in terms of its tangible effects.

Sanford Levinson, a UT professor of law and government who specializes in constitutional law, said that more traditional legal scholars were skeptical of empirical research and tended to assume data could be manipulated to yield any conclusion.

“Before that work, Liz, like most of the rest of us, read a lot of legal cases, thought about legal doctrine, but really hadn’t gotten her hands dirty working with hardcore data in the files of courts across the country,” Levinson said.

Back in Austin, with a team of research assistants, the team crunched numbers to find out precisely who was filing for bankruptcy, how much they owed and how they compared to the average American.

To Warren, perhaps the most surprising finding was that the debtors were not generally on the fringes of society. They were people who had pursued the trappings of the American dream — stable jobs, families, houses — and still lost.

“Part of me still wanted to buy the deadbeat story because it was so comforting,” Warren wrote in "Fighting Chance." “But somewhere along the way, while collecting all those bits of data, I came to know who those people were.”

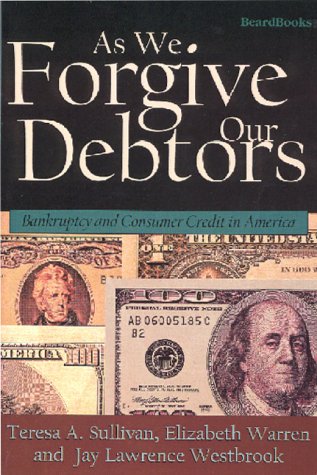

The research ultimately led to the 1989 book "As We Forgive Our Debtors: Bankruptcy and Consumer Credit in America."

As Warren's star rose in her field, she settled into life in Austin. She lived with her second husband, Bruce Mann, and her two children in northwest Austin. She occasionally rode to work with Calvin Johnson, who lived nearby. Johnson recalled having spirited debates with Warren that began when they got in the car, paused for the workday and resumed for the commute home in the evening. She and her husband frequently invited other faculty members over for dinner. When UT played the University of Oklahoma, the Oklahoma-born Warren rooted for the Sooners and teased her colleagues when they defeated the Longhorns.

Barbara Hensleigh and Portia Bott, law students at UT in the mid-1980s and leaders of the Women’s Law Caucus, both recalled admiring Warren as a dedicated teacher and one of the few women on the faculty. Though she supported and advised the caucus members as its faculty sponsor, she was not outspoken on women's issues, they said. Westbrook added that Warren often urged the faculty to hire more women, but would do so with a joke and a smile.

At the same time, Warren was becoming more outspoken on consumer economic issues.

Jack Getman, an emeritus professor at UT who specializes in labor law, said he and Warren discussed their research during jogs at a track near the law school.

“If you do that kind of work, you get to recognize how many ordinary people are struggling, and how decent they are, and how the system makes life difficult for them,” Getman said.

Warren began sparring with more traditional scholars of bankruptcy law whose work tended to argue debtors should be required to surrender more of their wealth to creditors to reduce the incentive to file. It was a notion that Warren gleefully mocked.

“This premise calls to mind thousands of almost-bankrupt rational maximizers sitting anxiously on some hypothetical cost/benefit curve, waiting for the numbers to come down from Congress,” Warren wrote in 1984.

She also had an ongoing dispute with Douglas Baird, a young professor at the University of Chicago who, like Warren, studied bankruptcy but ascribed to a more pro-creditor, theoretical approach to the subject. In 1987, they published a series of essays on their fundamentally different outlooks. Warren made a case for her research methods and the human narratives they uncovered.

“I cannot claim that bankruptcy, at its heart, is an intellectual construct or that I can reason to a meaningful conclusion by doing nothing more than thinking hard about logical consequences derived from a handful of untested assumptions,” Warren wrote. “I would like to endorse something that requires only library time and yellow legal pads to uncover ideal solutions to legal problems. The trouble is that I can’t do it.”

Professionally, Warren flourished at UT. But personally, she had a problem: Mann, her husband, a legal historian who had been a visiting professor at UT, was not hired for a full-time, tenure-track position. He taught at Washington University in St. Louis and shuttled back and forth to Austin.

Patricia Cain, now a professor at Santa Clara University School of Law, was one of first female professors at UT-Austin's law school. In the mid-1980s, she was in a relationship with a law professor who then taught in California, and she recalls commiserating with Warren about the strain of balancing two academic careers and family life.

“Liz and I used to go out and cry in our beers that we couldn’t get our partners hired by the law school,” Cain said. “It was emotionally draining to spend a weekend as a family and then it’s either Sunday night or Monday morning, you’re splitting up again.”

Warren’s colleagues at UT said they knew it was only a matter of time before another school made the couple an offer. The University of Pennsylvania eventually made an offer too good to pass up. Though UT ultimately also offered Mann a full-time job at the school, Penn had promised Warren a $10,000 raise and bested Mann’s offer from UT by $5,500, according to correspondence among law school administrators that are included in Warren’s employment file at UT.

In the resignation letter she submitted in the spring of 1987 to Mark Yudof, the law school dean, Warren expressed “great reluctance” at leaving Texas but said the compensation and opportunities available at Penn were “simply too great to resist.”

“I will miss the faculty, the students, the administrative staff, the library — in short, everything special that makes UT what it is,” Warren wrote.

Warren would continue her research and writing with Sullivan and Westbrook over the next decade. "As We Forgive Our Debtors" was not published until two years after she left UT, and the trio published "Fragile Middle Class: Americans in Debt" in 2000, after Warren had left Penn for Harvard.

To an unusual degree, she would build on the scholarship she did at Texas in an altogether different arena: politics. In 1995, she was appointed to advise the National Bankruptcy Review Commission, where she advocated unsuccessfully against legislation that made it harder for consumers to declare bankruptcy. She headed the Congressional Oversight Panel that reviewed the Toxic Asset Relief Program after the Great Recession. In 2011, many viewed the Obama administration's creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau as a vindication of the arguments Warren had first began making at UT — that the American middle class needed more safeguards against abuse and manipulation by financial institutions.

And in 2012, to the surprise of her UT colleagues who still viewed her foremost as an academic, Warren ran against Republican Scott Brown for a U.S. Senate seat in Massachusetts.

“I would tease Liz, why are you doing all this stuff, kissing babies and so forth, when you could be doing great scholarship?” Westbrook recalled.

Since taking office, Warren has occasionally clashed with members of the Texas Congressional delegation, notably unleashing a barrage of tweets in April criticizing Sen. Ted Cruz for a fundraising email in which he discussed the “significant sacrifices” he made while running for president.

But she still makes it back to the Lone Star State to catch up with colleagues — and occasionally fulfill her new role as Democratic energizer-in-chief. Last September, she headlined a sold-out fundraiser for Texas Democrats at Scholz Garten in Austin.

Though some former colleagues expressed doubt about whether Warren would want to be anyone's vice president, Westbrook thinks Warren could be convinced.

“For example, if Mrs. Clinton were to carve out areas, for example bank regulation, where Liz could kind of be in charge ... and she felt that the president would stand behind her, I think she could be persuaded,” Westbrook said.

Disclosure: The University of Texas at Austin and the University of Houston have been financial supporters of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors can be viewed here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Isabelle_TaftTT.jpg)