Race and UT-Austin Admissions: A Snapshot of the Past Five Years

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/SunsetUT.jpg)

In a decision awaited by colleges across the nation, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Thursday that the University of Texas at Austin could continue to consider race as part of its application evaluation process.

The surprising decision upheld a highly controversial admissions system that has been in place at UT-Austin since 2004. Here's a graphical look at that process and how it has affected the selectivity and diversity of one of Texas’ two flagship universities.

UT-Austin applicants are essentially split into two groups: the students who get in automatically because of their class rank and the other applicants who are evaluated through a "holistic" review, based on their rank, test scores, race and other factors.

The automatically admitted students are accepted under a state law known as the Top 10 Percent Rule. Under the rule, any applicant to any state college who ranks near the top of their Texas public high school’s graduating class gets in, no matter what. (To get into UT-Austin, a student needs to be in the top 7 percent; everywhere else, it’s the top 10.)

The rule’s purpose is to make Texas’ top universities more accessible. Texas’ public schools are largely segregated, and the schools with more Hispanic and black students tend to have fewer resources and produce fewer students who excel on their SATs. So in theory, promising a spot at UT-Austin to students from every school will increase diversity at the university.

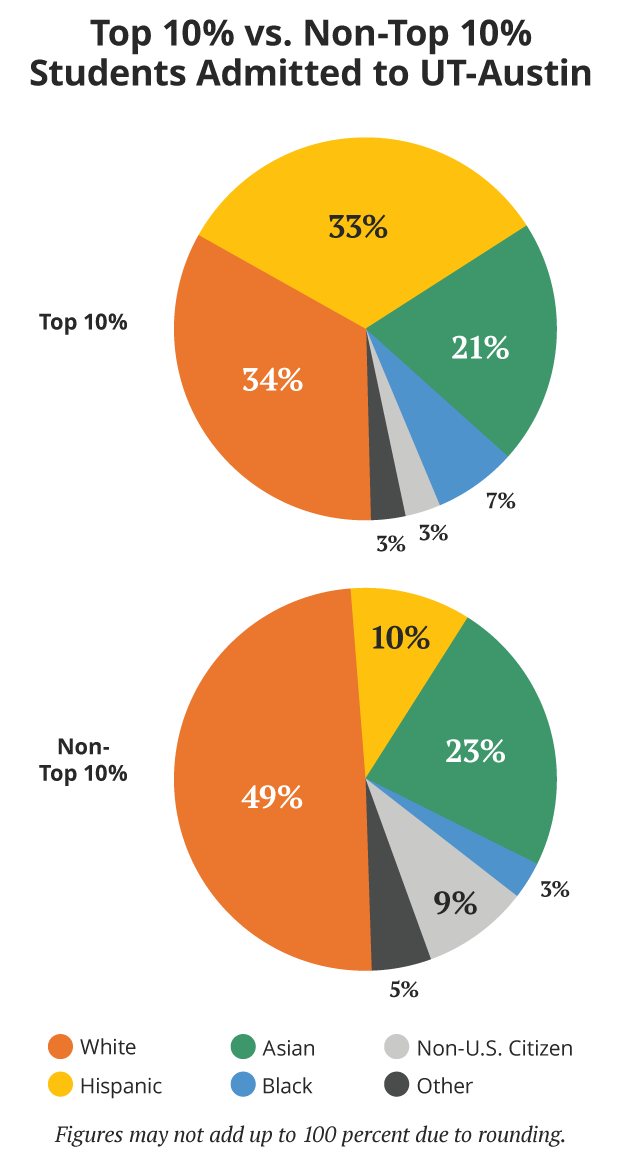

The first chart indicates that the rule works — at least a little bit. Hispanics make up 33 percent of top 7 percent admittees, compared with just 10 percent of students admitted under the school's holistic process. Meanwhile, black students made up 7 percent of automatically admitted students, compared with 3 percent of Hispanic students admitted after holistic reviews.

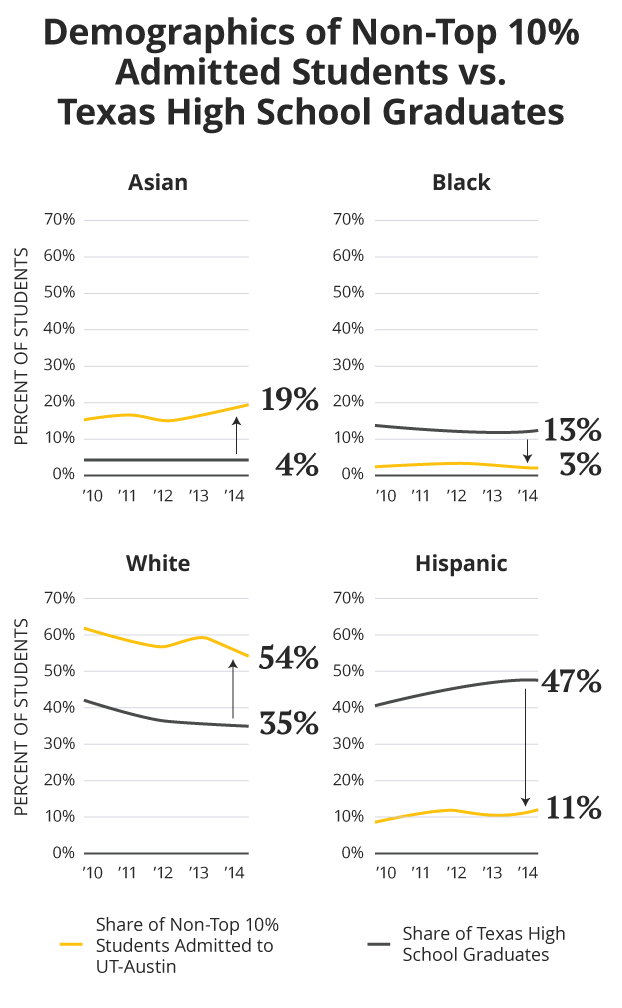

The chart below shows that students admitted under the holistic review look much less like the students graduating from Texas high schools. (Data on high school graduates, which is provided for students who finished high school in four years, isn't yet available for 2015).

Juan Torres and Emily Albracht

Black and Hispanics make up just 14 percent of students admitted from outside the automatic threshold, even though they make up 60 percent of Texas high school graduates. Meanwhile, white and Asian students make up 73 percent of non-automatically admitted students, while they make up 39 percent of Texas high school graduates overall.

But still, UT-Austin’s opponent in the Supreme Court case argued that the holistic review process was unfair. Abigail Fisher, a white student from Sugar Land, said she would have gotten into UT-Austin in 2008 if the school were not using race in admissions when considering non-top 10 percent applicants. And she argued that the Top 10 Percent Rule represented a “race-neutral” way to increase diversity, so affirmative action was unnecessary.

With the case settled, attention will now probably turn to the Top 10 Percent Rule. Many conservatives in Texas say the rule is unfair to students who attend competitive schools. Many students who are outside the top 10 percent at those schools have polished résumés and excellent scores on the SAT, they say. Those students, who attend schools that are overwhelmingly white, would be able to get into UT-Austin if it weren’t for the rule, they say.

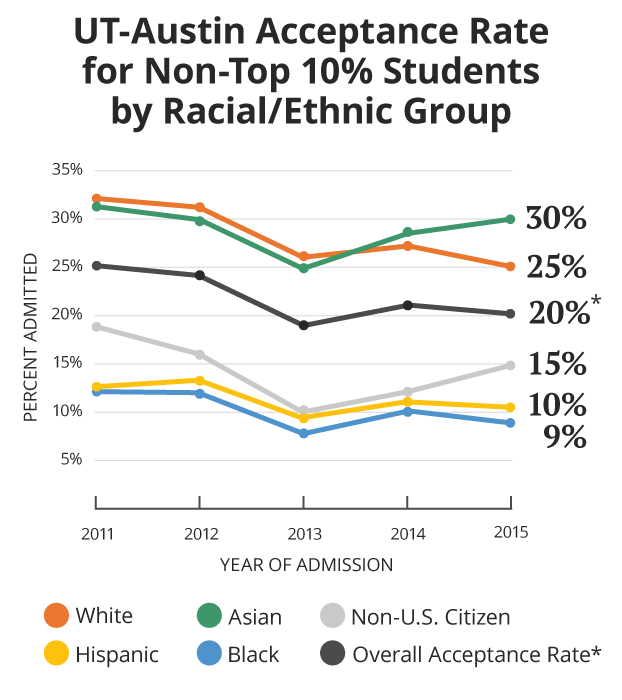

So what does the data show when it comes to the use of race in admissions at UT-Austin with non-Top 10 Percent applicants? In 2015, there were 33,490 applicants who were not eligible for automatic admission; 6,768 of them got in.

That means the acceptance rate of non-automatic admittees to UT-Austin in 2015 was 20 percent, a number similar to the overall rate of Washington and Lee University in Virginia or the University of Notre Dame.

And evaluating those non-automatically-eligible students by race shows that white students have a much better chance of getting into UT-Austin than black and Hispanic students. In 2015, The admission rate for non-automatically-eligible white students is 25 percent. It was 9 percent for black students and 10 percent for Hispanic students. See the chart below.

Juan Torres and Emily Albracht

UT-Austin declined to comment for this story. But a few things are evident from legal briefs and public statements that school officials have made in the past. For one thing, the university would dispute that the Top 10 Percent Rule is a more effective way of achieving diversity simply because students admitted under the rule are more racially diverse. The school has argued there are other ways to define and achieve diversity.

Also, UT-Austin, like many other universities, is always seeking out more students with high SAT and ACT scores. But most of its freshman class is admitted based solely on grades because of the Top 10 Percent Rule. So when the school considers students who are not automatically eligible, it is especially interested in high test scores — and white and Asian students are more likely to fit that profile.

Finally, in legal briefs, the school has acknowledged that its non-Top 10 Percent admitted students are not racially diverse. In fact, the school says, that's why using race is so important for that pool of students. If the school didn't use race, the pool would be even less diverse, the briefs say.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy appeared to agree with some of the university's points regarding the Top 10 Percent Rule in his majority opinion issued Thursday.

Using the Top 10 Percent rule exclusively, Kennedy wrote, "would sacrifice all other aspects of diversity in pursuit of enrolling a higher number of minority students." A "star athlete" or musician with lower grades would be excluded from the university, he wrote.

In an impassioned, 60-page dissent, Justice Samuel Alito had a very different view.

"Ultimately, UT’s intraracial diversity rationale relies on the baseless assumption that there is something wrong with African-American and Hispanic students admitted through the Top Ten Percent Plan, because they are 'from the lower-performing, racially identifiable schools,'" he wrote.

Matthew Watkins contributed to this report.

Juan Torres is the innovation editor at Correio newspaper in Salvador, Brazil. He recently spent three weeks at The Texas Tribune as part of an International Center for Journalists fellowship program.

Disclosure: The University of Texas at Austin has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors can be viewed here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Neena_1.jpg)