One Year, Two Races: Inside the GOP’s Bizarre, Tumultuous 2015

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2015/09/17/GOP_Debate_2_Full.jpg)

June 15, 2015

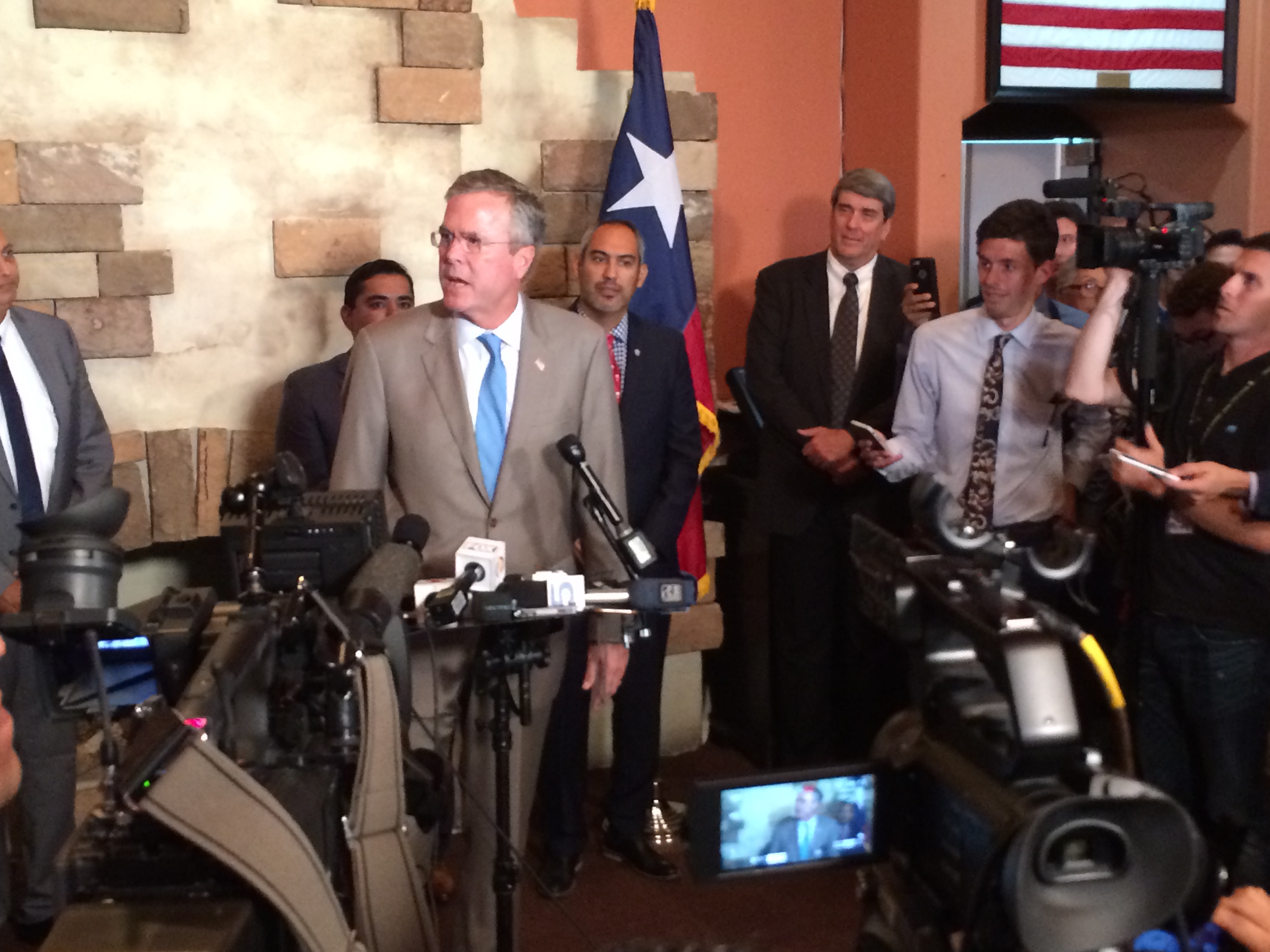

It is an oppressively humid day in South Florida and Jeb Bush has come home to declare his candidacy for president. The big crowd assembled at Miami Dade College is festive — and diverse, reflecting the culture of Miami that has shaped the former governor for decades and the kind of openness he believes his party needs to win the White House. Bush has had a difficult spring, his candidacy buffeted by criticism and self-inflicted wounds. But in many circles he is still seen as the politician to beat for the Republican nomination.

His speech evokes what he hopes voters will see in him, someone with executive experience, conservative values and a reformer’s instinct — and perhaps above all, electability. “I will take nothing and no one for granted,” he says. The speech draws strong reviews, his best moment yet. For Bush, it is a day to put his problems behind him and begin the campaign anew.

June 16, 2015

The scene at Trump Tower on New York’s Fifth Avenue is surreal. Down the escalator, his image reflecting on the walls around the lobby, comes Donald Trump, the billionaire developer and reality TV star. The crowd gathered in the lobby is large and boisterous. Later it will be revealed that some were paid to attend — an arrangement the candidate would not long need.

Trump is there to announce, to the surprise of so many, that he will seek the White House. He has flirted with this before but always stopped short. Now he says he is in. His speech is seemingly off the cuff. He goes after China and President Obama and then turns to immigration. Mexico is sending their worst across the border, he says — drug dealers, rapists and murderers among them. The language is harsh — shocking to many — and draws instant condemnations. For the novice politician, it is an inauspicious start to the campaign.

The year 2015 will be remembered as one of the most bizarrely compelling and yet genuinely unnerving in the nation’s modern political history.

It is clear now that there were two halves to the year for the Republican Party: BT and AT, Before Trump and After Trump. From January to mid-June the story of the Republican race was mostly conventional, with Bush the focal point for good and ill. There were unanticipated twists, among them the sheer size of the field of candidates — ultimately a total of 17 who would formally declare.

Those early months, however, were only a prelude to the real events that would follow. It is hardly overstatement to say that, on June 16, everything changed — though no one knew it at the time, not even Donald Trump.

Trump’s entry brought scorn and dismissal. He was a clown, a carnival barker, the leading man in a sideshow with a short run. His outrageous rhetoric — an appeal to nativism and antipathy toward everything from institutional powers to cultural shifts — seemed to guarantee all that.

Yet even on that day in June there were signs that the elites in the party and in the political community didn’t get what was stirring. From New York, Trump flew to Iowa for a rally at Hoyt Sherman Auditorium in Des Moines, where he was cheered as he strode down the aisle to the front stage.

Don and Kathy Watson were among those who had come to see him. Asked why Trump, she replied: “Why not? He’s as good as anybody. . . . He’s not afraid. He’s not a politician.” They weren’t certain they would support Trump, but they knew which candidate they would not support: Bush. “Dump him. We’ve had too many Bushes,” she said.

Trump’s reception that night showed that whatever the party establishment thought of him, many voters found him instantly attractive. Those early sentiments underscored the festering emotions that would soon burst forth, frustrations born of economic stress and disgust with Washington.

By the end of the year, every candidate running for the nomination could sense it — and all were trying to adapt, channeling the anger as best they could. Some adapted well, and may yet win the nomination. Others didn’t make it to the New Year.

Aboard his campaign bus in Iowa two days before the arrival of 2016, Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida reflected on what he had seen and felt through the amazing year of 2015.

“People are just tired,” he said. “They’ve tried Democrats, they’ve tried Republicans. They’ve tried a combination of both. They’ve tried new people, they’ve tried old people and nothing changes. Things get worse. They don’t seem to get better, no matter who’s in charge; it feels like the country is stuck in neutral and people are fed up and that’s what brings us to the point where we’re at today.”

What Rubio said was an echo of what almost every Republican candidate was saying by the end of the year. But as the election year opens, the lingering question — the big unknown — is whether 2015 will prove to be an aberration, a holiday from reality or a portent of things to come.

What is clearest is what didn’t work in 2015, though it often worked in the past. Television advertising moved few voters. Policy rollouts fell on deaf ears. Impressive political résumés proved not to be persuasive. What took on the Republican side was a new kind of politics, one built on emotion and visceral connection. To some people, this represented a worrying turn toward a darker and more divisive politics. To others, it was a welcome turn away from what they considered to be too much political correctness.

Rick Santorum said of Trump: “He may have understood the game better than any of us.” But like so many people, the former senator from Pennsylvania wondered whether the billionaire mogul understands the game ahead. It is the question that hovers over everything in politics at this moment.

“I think the vote is much different than a poll and so I want to see what happens when people actually vote,” New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie said in evaluating 2015. “Then we can start talking about eras being defined or newly established.”

The answer will come soon enough. What follows is the story of how Republicans got to where they are today, told primarily through the impressions, recollections and analyses of those who lived it personally — the Republican candidates. This article is based almost entirely on on-the-record interviews with most of the major candidates — some of whom fell away — and with their advisers and other strategists. It is the story of a remarkable year in American politics.

The question that hovered over the Republican Party a year ago was very different: Will he or won’t he?

In late 2014, the he in question was Jeb Bush. A son and brother of presidents. A towering figure in Florida politics. A cerebral executive celebrated for his policy chops and conservative record as governor. Though hobbled by his support for immigration reform and Common Core educational standards, Bush was seen by party elites as a man literally groomed for the office — a president at the ready.

The reality would prove to be more complicated. Out of office for eight years, Bush was rusty, and through the fights of the Obama era that reordered the political right, he was largely absent.

To demonstrate that he was in touch with politics in the age of social media, Bush went on Facebook on Dec. 17 to declare that he was actively exploring a run. The announcement landed like a thunderclap, instantly thrusting him to the top and undercutting a slew of other establishment hopefuls, especially Christie and Rubio.

“Any time someone with the last name Bush gets into a national race, the first impact you feel is fundraising, and that’s certainly the one that we felt most immediately,” Christie would later recall. “A lot of people started to sign on with him before we’d even gotten off the ground. It was his attempt, I think, to preempt the field.”

Sally Bradshaw, senior adviser to the Bush campaign, said there was no expectation of clearing the field — quite the opposite. “We knew this would be a more crowded and talented field than 2012 and we knew the electorate was angry at President Obama,” she said. “We assumed there would be an establishment candidate or several and an anger candidate. Our assumption was that [the anger candidate] would be Ted Cruz. No one anticipated a Trump candidacy at that point.”

Bush’s aggressive effort to raise funds in early 2015, Bradshaw said, reflected the campaign team’s assumption that the nomination contest would be highly competitive and potentially lengthy.

“Shock and awe” is how it came to be called, to the chagrin of Bradshaw and others. Still, it was a genuine blitzkrieg. Bush’s advisers established Right to Rise, a super PAC that could accept unlimited contributions, and it vacuumed up big checks by the day. On Jan. 9, it received its first $1 million contribution, from Los Angeles investment banker Brad Freeman. By February, Bush was averaging one fundraiser a day and regularly headlining events with a minimum price tag of $100,000 a person, such as the Feb. 11 gathering at the Park Avenue home of private-equity titan Henry Kravis.

Longtime Bush family fundraiser Fred Zeidman recalled: “Everyone was enthusiastic, everyone was writing checks. That had always been the benchmark. Money has been the way you keep score.”

The intense early pace startled Bush’s likely opponents. “I think everybody was a little surprised as to not just the timing but how successful he was early on,” Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker recalled later.

Donors who had been contemplating backing Christie, Rubio or Walker were suddenly on board with Bush. “Are they raising a lot of money? Yeah,” Ray Washburne, a Dallas real estate developer who was leading Christie’s fundraising efforts, said at the time. Washburne’s candidate was not. “We’re in the making-friends stage.”

The swaggering entrance of Bush was perhaps most acutely felt by Rubio.Bush’s one-time protégé, Rubio enjoyed an overlapping donor network with him, especially in their shared home state of Florida. Yet at the onset of the so-called invisible primary, many of these people were publicly signing on with Bush before Rubio could even make the hard sell.

“It just changes completely the way you have to go out and raise money,” Rubio recalled later. He said he resorted to building a more grass-roots donor network, as he did in his 2010 Senate race when he began far behind the hand-picked candidate of party leaders, then-Gov. Charlie Crist. “You have to find new people that haven’t traditionally been involved in the past, but want to see a change in America.”

As Bush jetted from mansion to mansion securing donors, Bradshaw and Bush’s longtime political consigliere, Mike Murphy, were mapping out the campaign. They were confident about Bush’s chances to be the nominee. Sure, he would have to overcome America’s historical aversion to dynastic politics and the country’s lingering distaste for the George W. Bush years. But he would easily establish his own political identity, they figured. He had done it in Florida. His campaign signs and bumper stickers always bore the logo, “Jeb!,” with a giant red exclamation point emphasizing that he was not just another Bush. They would do so again.

Bradshaw and Murphy envisioned the general election against Hillary Clinton, the presumed Democratic nominee. They would try to master the data and digital frontier that Obama so effectively exploited and that had bedeviled Republicans. Bush would visit urban areas and tour schools in impoverished neighborhoods. He would deliver an optimistic pitch to the middle class. He would woo Latinos with a compassionate approach to immigration, by campaigning in Spanish and by showcasing his Mexican American wife and blended family. His slogan would be “right to rise,” a shot for everyone to climb up the income ladder.

Out in the heartland, there were rumblings of resistance among the constituency that had not yet shown much interest in a third Bush presidency: voters. A dozen Denver-area residents — Republicans, Democrats and independents — registered a startlingly negative view on Bush during a two-hour focus group moderated by Democratic pollster Peter Hart for the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

When an information technology program manager named Charlie Loan, a Republican-leaning independent, said half-seriously that he would be happy to see Congress pass a law banning anyone named Bush or Clinton from running for president, half the people in the room agreed. And when the participants were asked for short impressions of Bush, the responses included: “No, thank you;” “Greedy;” and, “Again?” The closest anyone came to showing enthusiasm for Bush was, “intriguing.”

As Bush was fast building his juggernaut, a threat emerged on the horizon. Mitt Romney, who had run for president twice before, had grown restless in the two years since conceding to Obama. The world seemed like it was on fire; back home, the middle class was getting crushed. Romney was itching to get back in the game, to have a shot at turning things around.

One night in early January, aboard a red-eye flight from San Francisco to Boston, Romney wrote in his journal: “If I want to be president, I’m going to have to run for president.”

In Romney’s mind, there was no if. And at a Jan. 9 gathering of some of his top 2012 campaign donors in Manhattan, hosted by New York Jets owner Woody Johnson, he made his feelings known. “I want to be president,” Romney told the assembled financiers.

Romney’s surprising declaration electrified the Republican money and operative class and set off a tumultuous three-week period of public deliberation.

“This wasn’t going to happen by a claim of some kind or other people having a difficult time getting traction and then people turning to me and asking me to run,” Romney recalled thinking at the time. “If I wanted to be president, it was a decision I had to make. And Jeb, I think very wisely, had begun raising money and getting things started early on, so the time frame to make that decision was earlier than I might have thought.”

Romney called his former donors, dozens of them, and received encouraging feedback. His chief fundraiser, Spencer Zwick, estimated that they could raise the $100 million or so necessary to get through the primaries. Longtime adviser Beth Myers assured him he could assemble a top-notch staff.

Strategist Stuart Stevens kept counseling Romney to make a personal decision, not a political one, though Romney studied the politics closely. Chicago investor Muneer Satter, a GOP mega-donor, commissioned polls from a dozen or so states and showed the data to Romney.

“Am I loved? Am I written off? Am I despised? What does the Republican base think about me?” Romney recalled wondering.

He liked what he saw. Romney said the polls showed him with commanding leads among potential Republican candidates in New Hampshire and Nevada and a smaller lead in Iowa. In South Carolina, he was tied at the top with Bush and others.

“It’s like, ‘Wow. Wow.’ That’s not a bad place to start from,” Romney said in a late-December interview in Boston at the well-appointed offices of Solamere Capital, the private equity firm run by Zwick and Romney’s eldest son, Tagg.

Romney thought that if he got in, he was better positioned than anybody else to get the nomination. He was more concerned about the general election. He saw Clinton — because of both the historic nature of her candidacy and the demographic advantages Democrats enjoy at the presidential level — as a formidable opponent.

The reaction outside Romney’s orbit was less rosy. Governors, senators and other Republican leaders called him a decent man who has served the party well, but said his time had passed.

On the right, the criticism was sharper. The Wall Street Journal editorial board lacerated him in a column headlined, “Romney Recycled.” Rupert Murdoch, whose company owns the Journal and Fox News Channel, said: “He had his chance, he mishandled it, you know? I thought Romney was a terrible candidate.” Talk radio host Mark Levin summed up the sentiment in a tweet: “Been there, done that.”

Of the barrage of negativity, Romney suspected a culprit: “I recognized the hand of my good friend, Mike Murphy, [who] in my view was fanning the flames of, ‘No, he’s the disaster. It would be terrible. Only Jeb!’ I must admit that had the opposite effect [than] he might have intended, which is just like, ‘I’ll show them.’ ”

Murphy, the Bush adviser, said this was “absolutely not true” and that he did not talk down Romney’s chances with commentators, governors or senators. “I’m sorry he thinks that,” Murphy said, noting his long relationship with Romney. “I think the doubts were more organic than he believes.”

Romney believed that, if he passed on the race, Bush would be the most likely nominee. Privately, he harbored serious doubts about Bush’s ability to beat Clinton. He recalled thinking, “I like Jeb a lot, I think he’d be a great president, but felt he was unfairly but severely burdened by the W. years — and when I say the W. years, it’s not only what happened to the economy, but the tragedy in Iraq.” He added, “A Bush-versus-Clinton head-to-head would be too easy for the Democrats.”

On Jan. 22, Bush flew to Utah, where the Romneys were settling into a new home in the Salt Lake City suburb of Holladay, to pay Mitt a courtesy visit. The date had been set long before Romney expressed interest in running. The two men exchanged pleasantries and updated each other on their growing families; four days earlier, Romney’s 23rd grandchild was born.

Then they got down to business. Romney told Bush about the private polls that showed him performing well in the early voting states. “It’s opened up a door that I didn’t think would be open to me,” he recalls telling Bush.

Romney also said he confronted Bush with his fears about his candidacy: “Jeb, to be very honest, I think it’s very hard for you to post up against Hillary Clinton and to separate yourself from the difficulty of the W. years and compare them with the Clinton years.” He said Bush responded by saying that “he was going to make his campaign about the future, not about the past.”

“I didn’t say anything at that point,” Romney recalled. “But as he left, I said to myself, ‘Gosh, in my opinion, it’s not going to be as easy to make that separation as I think he gives the impression it will be.’ One of the few things I predicted that turned out to be true.”

Bush, through a spokesman, declined repeated requests to be interviewed. Bradshaw said: “We don’t talk about meetings that we consider to be private. We’re honoring Governor Bush’s commitment to Governor Romney to keep the meeting private. Governor Bush appreciates what Mitt did in waging an able campaign and leading our ticket.”

With his exploration continuing in public, Romney more and more was leaning against running. Wife Ann supported the idea and wanted Mitt to be president, but their five sons were split. Tagg and Josh were for it, Matt and Craig were against it and Ben was on the fence. Romney suspected their wives were opposed, though they kept their opinions to themselves.

Romney privately consulted two of his closest friends in elected office: Rep. Paul Ryan of Wisconsin, his 2012 vice presidential running-mate whom he earlier had been badgering to run himself to no avail; and Sen. Rob Portman of Ohio. They didn’t discourage Romney, but neither did they push him to jump in.

“They were friendly and encouraging,” Romney recalled, “but cautious and saying, ‘Gosh, we need an elder statesman in the party. . . . If you get into the race, why it diminishes you. You’re now one of the big crowd of people running and you lose the impact you could have had.’ And they said, ‘Maybe you’re not as able to win the general as perhaps someone coming along.’ ”

Romney was arriving at the same conclusion. He remembered thinking, “It’s going to take something unusual, something catching lightning in a jar to beat [Clinton], and the guy who ran before isn’t very likely to catch lightning in a jar. I’m too well known. I’m too well defined.”

On Jan. 30, exactly three weeks after declaring in New York that he wanted to be president, Romney announced that he was giving up on the dream. He did so with what many interpreted as a knock against the front-runner, Bush.

“I believe that one of our next generation of Republican leaders — one who may not be as well-known as I am today, one who has not yet taken their message across the country, one who is just getting started — may well emerge as being better able to defeat the Democratic nominee,” Romney said. “In fact, I expect and hope that to be the case.”

Some of those young stars Romney had in mind were fresh off another successful midterm election. Descending on Florida for the Republican Governors Association’s annual meeting, they were ebullient and looking ahead to their possible White House runs. It was only November of 2014, but the corridors of the ornate Boca Raton Resort & Club were a grand bazaar of political gossip and speculation. Greg Abbott, just elected governor of Texas, joked, “I think everyone in this building is running for president.” As they looked toward 2016, many Republicans believed the nomination battle would become a fight among the governors.

The state executives were stars in the party, seen as models of conservative governance in contrast to the dysfunctional family of Republicans in Congress. Moreover, at a time of public disenchantment with President Obama, who was elected more on charisma than experience and whom Republicans derided as never having run anything before, the governors thought they would be the likeliest antidote.

The list of prospective candidates from these ranks was long: the outgoing Texas governor Rick Perry, who after a record 14 years in office could boast of sizeable job creation numbers; Christie, who began 2014 in scandal surrounding the closure of lanes leading to the George Washington Bridge but ended it taking a victory lap as outgoing Republican Governors Association chair; Ohio Gov. John Kasich, newly reelected in a landslide in one of the most important swing states in the country; Walker, nationally known among conservatives for his battles with unions and who won three tough elections in four years; and Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal, a policy wonk and idea generator.

Those were just the sitting governors. Beyond that were the former governors: Bush, Mike Huckabee (Ark.), George Pataki (N.Y.) and Jim Gilmore (Va.).

Governors appeared to have the best of both worlds: experienced as chief executives and able to portray themselves as Washington outsiders. As Walker explained more than a year later, governors “could all make an argument that we were outside of Washington, that we’re getting things done, that we were part of a movement of governors across the country – all of which is accurate.”

Many of the governors who were preparing to run had one overriding goal in mind: to become the alternative to Bush. In Bush’s camp, the other governors loomed largest as potential competitors, although which one was most threatening remained a mystery.

Perry, who had run a disastrous race for president in 2012 and had spent two years preparing for a second campaign, already could see the landscape ahead — a nomination contest that ultimately would come down to a competition between two men who had led two of the biggest states in the country.

“I full well thought that by the fall of 2015, Jeb Bush, Rick Perry were going to be on the stage having a thoughtful conversation about each of our competing visions for America and us comparing our records of success,” Perry said in a December interview.

Perry judged himself and Bush to be “two of the most successful Republican governors maybe in the history of the country.” Surely, he believed, “the American people would distill down which of these individuals had the best vision for America. . . . It was going to be me and Jeb.”

The challenge was to break out from the pack. The first to do so was Walker, who delivered a fiery speech on Jan. 24 in Iowa at a day-long Freedom Summit, sponsored by the group Citizens United and hosted by Rep. Steve King, one of the most conservative members of Congress.

By showing real passion, the bland politician had surprised those who didn’t know him — including many in the national press corps who had descended on Des Moines for the first major Republican event of the cycle. Conservative talk radio was abuzz about him. For days on end, Rush Limbaugh hailed the Wisconsinite as the cure to what ails the Republican Party.

At the time, Walker later recalled, he found it amusing. “I laughed with the coverage that came out — ‘Oh, Walker gives his breakout speech,’ ” he said. In his own mind, it was no different than the performances he delivered on factory floors or at small rallies during his reelection in the fall of 2014.

The media attention to Walker gave him a significant boost, even though others such as Cruz, the senator from Texas, and even Trump stirred the conservative audience nearly as much.

With the attention came a brighter spotlight, and Walker then suffered through a series of errors. In London, during an official state business trip, he declined to say whether he believed in evolution. In an interview, he wouldn’t say whether he believed Obama was a Christian. At the annual Conservative Political Action Conference, he appeared to cast his battles with the unions as a proving ground for his capacity to deal with Islamic State militants.

Walker wrote off the incidents as minor problems. And the missteps did not arrest his rise, at least not then. He soon became the poll leader in Iowa and, in the quickly congealing world of conventional wisdom, was described as the principal challenger to Bush.

As he traveled the country early in the year, Walker believed he was particularly well suited for a GOP electorate whose frustrations, even with their own party leaders in Washington, he could feel.

“Part of our assessment was, I can say I’m the guy who didn’t back down. If you want somebody who’s going to stand up and get these sorts of things done, I can do it, I did at Wisconsin, we can do it going forward,” Walker recalled. “I think that was part of our initial appeal. What we didn’t see coming along the way was just how intense that frustration was.”

If governors planned to run on their records of enacting reforms back home, a trio of first-term senators were hanging their hopes on their potential to disrupt Washington’s established order.

The first out of the gate was Cruz, a combative conservative who, in his 14 months in the Senate, had made many more enemies than friends. An Ivy League-educated lawyer, Cruz already had proven himself a smooth orator and wily tactician. He was best known for leading a 2013 crusade against Obama’s health care law that resulted in a partial shutdown of the federal government.

Cruz arrived on the presidential stage as a hero to tea party activists, but he had another objective: to make himself a hero to evangelical Christians and libertarian conservatives, too.

“Conservatives have always outnumbered moderates in a primary, but the way moderates have won previously is by dividing conservatives,” Cruz would later say. “Their strategy was to keep conservatives splintered. If conservatives ever unite, it’s game over.”

So on March 23, Cruz journeyed to Lynchburg, Va., to formally announce his candidacy at Liberty University, the private Christian college founded by televangelist Jerry Falwell. It was a splashy event. He spoke in the round at Liberty’s basketball arena before 10,000 cheering students. Like a pastor, he paced around the stage, no notes in hand, and gestured theatrically. He shared history lessons, invoked the Constitution and declared himself to be an uncompromising conservative and a champion of christian values.

Thanks to his national profile in the Senate, Cruz had a powerful network of small-dollar donors, as had conservative grass-roots candidates of presidential campaigns past. But even before announcing, he was moving stealthily and aggressively to woo wealthy power brokers in his home state of Texas, on Wall Street and beyond.

Energy investor Toby Neugebauer first met Cruz years ago and the two men, born just a few days apart, quickly clicked. Their families vacationed together. By February, Neugebauer had grown concerned there was not an effective, high-dollar super PAC operation to bolster Cruz. Neugebauer said to his wife, “Either we believe or we don’t believe.” And he soon approached other wealthy Cruz backers, over Texas barbecue and at Manhattan tête-à-têtes, with a proposition: If they put $10 million into a network of super PACs, so would he.

On April 9, Neugebauer wrote a check for $10 million. The next day, hedge fund executive Robert Mercer put in $11 million. And soon enough, Farris and Dan Wilks, brothers whose fracking services business had transformed them into billionaires, and their wives anted up $15 million.

“The money made the Cruz candidacy very real,” Neugebauer said, adding: “People realized, ‘This isn’t Michelle Bachmann.’ ”

Cruz’s campaign now had what no recent hard-right conservative candidate had: the resources to run a long campaign.

For Rand Paul in Kentucky, the ambitions on display across the Appalachian Mountains at Liberty represented a sudden threat, though Paul might not have recognized it at the time.

Paul, a sometimes-brusque maverick, embodied the tea party movement of 2010 when he catapulted from an ophthalmology practice in Bowling Green to the Senate. Paul’s father, Ron, had rallied libertarians during two quixotic bids for the presidency. Now Rand was aiming to do what his dad never could: win the Republican nomination.

Central to Paul’s hopes was expanding his base of libertarians and college students by picking up support from evangelicals. He was coming off an impressive 2014, when he traversed the country in the midterms, building alliances and courting big-league donors. He was organizing in Iowa, where some saw him as a genuine contender. Paul also was trying to grow the Republican Party’s cultural reach, giving speeches about race and other topics in such liberal enclaves as Berkeley, Calif.

In a Louisville ballroom on April 7, Paul declared his candidacy: “I have a message, a message that is loud and clear and does not mince words. We have come to take our country back.”

It was a day full of promise. Voters, Paul knew, were growing angry with what he derided as “the Washington machine.” Who better to win the nomination than a fiercely libertarian eye doctor-turned-citizen legislator? Little did he know then that a louder, brasher and angrier outsider would soon step forward.

This was a busy week in presidential politics. That Sunday, Clinton entered the race with studied understatement: a fast-paced and folksy video that featured little of the former first lady and secretary of state in favor of a diverse assortment of Americans talking about their hopes and aspirations for the spring. “Everyday Americans need a champion,” Clinton said, “and I want to be that champion.”

In Miami, Rubio and his advisers could hardly believe their good fortune. In just 24 hours, the ambitious young senator was set to make his formal announcement. What better way to enter the race than with a visceral comparison to the leading Democrat?

The son of Cuban immigrants, Rubio’s compelling biography helped accelerate his ascent in Florida politics. And to accentuate his story under the national spotlight, Rubio launched his campaign at the Freedom Tower, an iconic Ellis Island-like landmark in downtown Miami where a generation earlier U.S. officials processed Cuban refugees fleeing the Castro regime.

Rubio had been elected to the Senate in 2010 after taking on and defeating the establishment. After the party’s crushing defeat in the 2012 presidential election, he was a leading member of the Senate’s Gang of 8 that drafted an immigration reform bill, which included a path to citizenship for those here illegally.

He walked away from the legislation when sentiment inside the party shifted against that provision. But the issue remains a flash point in the Republican race to this day — and potentially one of Rubio’s biggest obstacles.

Rubio stepped forward under a banner that read, “A New American Century.” Charismatic and boyish — he was 43, but could have passed for a few years younger — Rubio offered himself as a next-generation president for a rapidly changing world. It was time, he said, to close the books on the past. Though he didn’t say their names, it was clear what he meant: the era of politics dominated by people named Clinton and Bush.

“Yesterday is over,” he said, “and we are never going back.”

Rubio now says his “yesterday” contrast was not only generational, but also about old ideas and stale solutions. “Ultimately, to the extent that there are people running who are not in touch with the realities of the 21st century, that contrast is going to be there,” he said.

In almost every presidential campaign, someone unexpected rises toward the top of the field. In 2015, that role fell to Ben Carson, a world-renowned pediatric neurosurgeon with no political experience. He would come to symbolize the hunger among many Republicans for someone, anyone, not tainted by politics as usual.

Carson was a novice to politics but has attracted a substantial following among conservatives and evangelicals. His life story was as compelling as any of the others seeking the presidency, if not greatly more so — a rise from poverty in his home town of Detroit to the top ranks of the medical profession. He broke onto the political scene two years earlier at the National Prayer Breakfast, when he sharply criticized Obama, who was sitting nearby.

Carson’s demeanor was jarringly calm in the high-volume world of national politics, which proved to be an early asset. But the transition from medicine, paid speaking and honorary degrees was not always smooth.

“The question at the beginning was whether we could raise money,” said Barry Bennett, a GOP campaign veteran who was brought on by Carson to manage his campaign. “So we started a fundraising list as Jeb’s super PAC was aiming for $100 million. That was hanging over us. We wondered, ‘Could we compete?’ ”

Millions poured in from his email list, which would grow to 3 million addresses, and from direct-mail solicitations. Carson had won informal straw polls across the country and became a phenomenon of sorts on the right — a kinder, gentler vessel for the frustrations within the Republican base.

“It was an outpouring of emotion for an anti-establishment person, very real, and a feeling, an emotion that the polls were never able to capture,” said Terry Giles, a former Carson adviser.

Carson was also a threat to some of those on the right who legitimately believed they were the rightful candidates to appeal to the wide swath of evangelical Christians who play an influential role in Iowa and many southern states.

Within weeks of Carson’s declaration of candidacy, Huckabee and former senator Rick Santorum of Pennsylvania also joined the race. They were the two previous winners of the Iowa caucuses, both over Romney — Huckabee in 2008 and Santorum by an eyelash in 2012.

Both were overshadowed by conservative newcomers and struggled to regain the support they had previously enjoyed. Huckabee would compare the dynamic to junior high school and boys’ fascination with the newest pretty girl in class.

“I’m seeing a lot of that in the presidential race,” he said in a December interview. “It’s that there’s the new-girl-in-school approach where you’ve got so many new girls in school. Some of us, we’ve been here since the first grade, so we’re having to just wait our turn to be remembered and liked again.”

Santorum said he anticipated that this would be the year of outsiders and felt that his 2012 campaign gave him credibility to tap the anti-establishment mood. “From my perspective, that’s what I did last time,” he said. “I took on the establishment. Four years had passed and there were more people doing the same thing and in a real-time way. . . . We were not in the headlines, not top of mind. We had been out of the fray. So from my perspective, I was starting all over again.”

The field of declared candidates grew quickly after Carson announced. The month of May brought in the only woman, Carly Fiorina, the former chief executive at Hewlett-Packard who lost a Senate race in California in 2010 in her only venture into politics. Also joining were Pataki and Sen. Lindsey Graham (S.C.). Rubio would later joke: “We live in a year when one out of six Republicans is running for president.”

Perry’s formal announcement came on June 4 at an airplane hangar north of Dallas. The backdrops included a C-130 transport plane similar to one that he had flown in the Air Force, a group of military veterans and an American flag that ran almost from floor to ceiling on one wall.

Perry’s speech laid down markers that he hoped would separate him from many of the others. The 2016 election, he said, would be a “show-me, don’t-tell-me” election, where voters prized records over rhetoric.

“The question of every candidate will be this one: when have you led?” he said. “Leadership is not a speech on the Senate floor. It’s not what you say, it’s what you do.”

Despite the growing field and the unsettled nature of the polls, much of the focus in the late spring remained on Bush, who struggled to connect with voters even as he excelled at raising money. By late April, Bush had something big to tout when he addressed 350 of his top financial supporters at a two-day donor retreat at Miami Beach’s 1 Hotel, an eco-friendly establishment with stunning vistas of the Atlantic Ocean.

The organization had already raised more money in 100 days than any other Republican operation in modern history, he told them. Still, some allies were restless. Why wouldn’t he just make it official and launch his campaign already? Why had his fundraising success not intimidated possible rivals from entering the race?

At an April cattle-call in New Hampshire, Bush laughed when a woman said he seemed to be the establishment’s chosen one and that she did not want to see a Republican coronation to match what she believed was happening with the Democrats. “I don’t see any coronation coming my way,” Bush responded. “Trust me.”

Murphy, the strategist, tried to quiet the concerns of donors who would have been happy with a coronation. During a closed-door briefing, he laid out the long game plan for Bush to secure the nomination and shrugged off the early polls as “noise meters.”

But shortly after Miami Beach, Bush inadvertently sparked another brush fire. When asked at a private donor meeting in New York in early May to whom he relied upon for advice on U.S.-Israel policy, he gave a surprising response: his brother, President Bush.

Suddenly, Bush was being pressed on the campaign trail to assess his brother’s legacy and most specifically the decision to invade Iraq. He stumbled for days, initially backing his brother’s decision, before asserting that, if he had known at the time that the intelligence was faulty, he would not have launched the invasion.

Bush’s donors and other backers continued to express concerns privately about his prospects. In an effort to build a more nimble and effective operation, Bush announced staff changes in the days before his formal announcement. The shake-up added to the worries of many Bush loyalists, but campaign officials insisted that they were on track to win.

July 4, 2015

It is the midway point of the pre-election year, a weekend for picnics, parades and candidate sightings in New Hampshire. Mitt and Ann Romney open their spacious summer home on Lake Winnipesaukee for some guests in the area: Marco Rubio and Chris Christie, two rivals for the nomination, and their families. Both candidates are planning to march in the parade in nearby Wolfeboro, where the Romneys are an annual presence along the route.

Mitt Romney, in T-shirt and shorts, cooks pancakes. Ann Romney, in her robe, fries the bacon as the guests assemble for breakfast. Politics is not on the agenda. But there is little relaxing on any weekend with the Romneys at the lake. There are boat rides and a trip for ice cream and a water slide into what Rubio, conditioned to the climes of South Florida, describes as freezing water.

It is a moment of congeniality in what everyone knows will only become more heated and personal. Rubio talks some pro football. It is July and he is still hopeful that his Miami Dolphins will actually field a competitive team for the season. He and Christie, both still low in the polls, are quietly hopeful that their seasons ahead will be successful as well.

Donald Trump’s Boeing 757 landed with a roar at Phoenix’s airport on a warm July afternoon. He stepped onto the tarmac in his uniform of dark suit and red tie — wisps of that famous hair turned up by the wind — and into a waiting black GMC Denali with a “TRUMP” license plate.

For the first time since his announcement, Trump’s seemingly long-shot presidential bid began to have the aura of a real, vibrating campaign: multi-city stops, a plane full of aides and security guards and piles of printed news articles about him and his rivals.

“Let’s go! Let’s go!” Trump said, clapping his hands in the style of a drill sergeant, as his entourage loaded into the caravan. In a region where illegal immigration has inflamed the public, Trump had come to capitalize on the issue. Approaching the venue, he marveled from behind the vehicle’s tinted glass at the thousands who had come to hear what he would say.

Trump later would acknowledge that he had been taken by surprise by the power of the immigration issue. “When I made this speech about illegal immigration, I had no idea what it was going to become,” Trump said. “I mean, it was an important subject to me but I had no idea it was going to resonate in the way it has.”

The Phoenix rally was strategically chosen to stoke the issue further. “We really wanted to punctuate where illegal immigration has had the most impact,” said Corey Lewandowski, Trump’s crew-cut and rail-thin campaign manager.

Backstage that day, Trump could hear the crowd stomping its feet and breaking into spontaneous cheers as his fans waited and sang along to his mix of Broadway tunes and hard-rock classics on the loudspeakers.

But instead of relaxing in his green room, Trump never even opened the door. He met for 20 minutes with families of people who were killed by illegal immigrants, taking pictures with each relative. The Phoenix rally came just days after an illegal immigrant, who had been deported five times, randomly shot and killed Kate Steinle, 32, as she walked along a pier with her father in San Francisco.

Trump treated local conservative politicians like old friends, including the controversial sheriff of Maricopa County, Joe Arpaio. He encouraged a GOP state treasurer to challenge Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) in a primary. “This is a movement,” he told a Washington Post reporter that day. He said it as a way of explaining the scene. But it sounded, too, like an assurance to himself.

National polls were charting an unexpected Trump surge. Days after he announced, an NBC-Wall Street Journal poll showed him at just 1 percent, with Bush at 22 percent. A week after the announcement, a Fox News poll put him at 11 percent to Bush’s 15 percent. A week after the Phoenix rally, a Post-ABC News poll showed Trump at 24 percent to Bush’s 12 percent. Bush would never lead again.

Despite the polls, few political strategists took Trump seriously. Nor were candidates seeing a need to fundamentally adapt their strategies. That soon began to change once it became clear that Trump was playing by different rules.

The first example came a week after the Arizona rally. At a Family Leader candidate summit in Iowa, Trump disparaged McCain, the party’s 2008 nominee and a Vietnam War POW who endured repeated torture.

“He’s not a war hero,” Trump said. With a tone of sarcasm, he continued: “He’s a war hero because he was captured? I like people that weren’t captured.”

Denunciations rained down on Trump. Candidates who had declined to criticize him for his immigration pitch suddenly felt emboldened to speak out. Surely, concluded many commentators, the attacks on McCain will bring a swift end to the Trump boomlet.

“I think the beginning of the end has come,” said Graham, himself a candidate and a close friend of McCain. “The beginning of the end has arrived because he’s crossed a line with the American people that will not be tolerated.”

Graham’s feud with Trump had begun even before the McCain attack. Trump’s immigration comments, he said, are “going to kill my party.” Trump, in retaliation, read aloud Graham’s cell phone number at one of his rallies. Graham responded first by changing numbers and then by producing a hilarious video on the many ways to destroy a cellphone.

But Trump’s surge continued, presenting all the candidates with a dilemma. Should they attack him, in hopes of accelerating what many thought would be an ultimate decline, or should they stay on course and hope that Trump would fade on his own?

Bush’s advisers telegraphed their theory: Bush would benefit from the amount of attention Trump was getting because he was drowning out the other candidates, including Walker and Rubio, who were positioning themselves to become Bush’s main rival.

But that assumption was based on the false premise that the Trump candidacy would burn itself out.

For Cruz, the anti-establishment senator, the playbook was counterintuitive: praise Trump whenever possible and steer clear of direct engagement. The senator from Texas hoped Trump’s supporters would be future Cruz voters, when and if Trump slipped. “I think he’s terrific,” Cruz said in a Fox News interview at the time.

Others hoped that the Trump phenomenon would run its course naturally. “Obviously Donald said things about us and we’ve had to respond to some of that,” said Rubio, who at various points found himself a target of Trump’s insults. “But even there we’ve tried to spend very little time doing that because every second I spend responding to his statement of the day is a second I’m not using to talk to voters about the future of America.”

Trump’s candidacy benefited immensely from the fact that he had spent a decade hosting the NBC television program “The Apprentice.” His celebrity appeal, combined with his blunt talk, produced a candidate unlike anything seen in the modern era of politics.

“We’ve never had someone, at least not in my lifetime, who was running for president before who, for the seven or eight years before that, had a top-10 rated national television show,” Christie said. “You cannot discount the celebrity factor in all this.”

Santorum offered a similar analysis: “He’s the same as he was on ‘The Apprentice.’ There is a sense of authenticity even though he’s all over the place on issues. . . . It’s, ‘We know that guy.’ ”

Bush and others jabbed at Trump over immigration in those early weeks, but it was Perry who decided to make a frontal attack. Perry’s rhetorical broadside came on July 22 in Washington.

“He offers a barking carnival act that can be best described as Trumpism: a toxic mix of demagoguery, mean-spiritedness and nonsense that will lead the Republican Party to perdition if pursued,” he said. Perry called Trump’s candidacy “a cancer on conservatism and it must be clearly diagnosed, excised and discarded.”

Many saw Perry’s attacks as a move of desperation by a candidate hoping to raise his poll numbers enough to make the main debate stage. Asked recently why he had given the speech, Perry said, “Because it was true, and that’s what I felt.”

After months of positioning, the candidates descended on Cleveland to share a debate stage for the first time. There were 17 of them — so many that they had to be divided into two groups: the top 10 would debate at prime-time; the others in an earlier undercard.

The leading candidates were escorted out of their green rooms and into a freight elevator. Together, they rode down to the floor of the Quicken Loans Arena, where the lights were shining bright and the Fox News anchors were made up and ready to start asking questions. Not in recent memory had the party fielded such a deep roster, nor had a primary debate been so hotly anticipated. Then again, a candidate like Donald Trump had never led the polls.

In the elevator, the nervous energy was palpable. The presidential aspirants were checking each other out, perhaps thinking that 11 months from that day, only one of them would be returning to this very arena, at the Republican National Convention, to accept the nomination. Matt Borges, the Ohio GOP chairman, made sure to be along for the ride: “Even for a grizzled old advance guy like me, that was a cool moment.”

For all the takes on what a Trump nomination might portend for the GOP brand or for conservatism itself, most Republicans agreed on what the nuclear scenario would be: Trump running in the general election as an independent. That would so divide conservative voters, they believed, that Clinton would waltz into the White House.

The first question tried to settle it once and for all. Co-moderator Bret Baier asked for a show of hands for anyone unwilling to support the eventual nominee and disavow an independent run. Trump, standing center stage, glanced quickly to his right. Not a single hand was in the air. Until he raised his.

It was the start of a rollicking night in which Trump landed on the debate stage like a hand grenade, as he had from the day of his announcement.

As Kasich later observed, “If I said one of the things he had said about Hispanics, Muslims or women, I’d have to go into a witness protection program.”

Watching the spectacle unfold, Clinton and her small army of a campaign team saw an opportunity. They would brand the whole GOP field as Trumpian. No matter who the Republicans nominate, they figured, Clinton was running against Trump. “They’re Trump without the pizzazz or the hair,” Clinton would come to say of the other Republicans.

In Washington, Reince Priebus, chairman of the Republican National Committee, was grappling for ways to gain control of his party’s nominating process. His carefully laid plans to limit the number of debates and reorganize the calendar after 2012 were challenged by the size of the 2016 field.

“For me, it’s just 14 candidates, it’s having 14 actually varsity-level people running for president,” Priebus would later say, after three had dropped out. “Every analysis — the convention, the delegates, the debates, too many, not enough — it’s the number of candidates to manage and calculate that makes everything else complicated.”

Even though Trump tongue-lashed party bosses in public, Priebus worked hard to develop a friendly personal rapport with Trump. After the Fox debate, Priebus sought to put the question about a third-party run to bed. He solicited signed pledges from all of the candidates vowing to support the eventual nominee. Most sent theirs back right away. For Trump, however, Priebus trekked up to New York to get the form in person. They met in the candidate’s Trump Tower office overlooking Central Park, where the billionaire signed the pledge and gave Priebus his assurances.

For the rest of the year, speculation would continue off and on about Trump going rogue. But Priebus wouldn’t flinch. “I’ve never worried about him running as an independent,” he said in a December interview. “I am not one tiny, little bit worried about it. He’s not doing it.”

By now, the Trump phenomenon was in full bloom. The candidate was reinventing political communication on the fly, calling in by telephone to cable programs day and night, and doing the same with Sunday morning talk shows, in contravention to the long-standing practice of requiring guests at least to be in a remote studio with a camera.

Cable television executives knew a hit series when they saw one.

The effect on other candidates was smothering. Walker said he quickly came to see that the focus on Trump kept him from breaking through. His policy rollouts, such as a prescription to overhaul the health care law, received scant media coverage.

“I remember, one time, I went into a meeting and I came out 50 minutes later, and I won’t say what network it was, but it was one of the cable networks, still covering Trump’s speech live, 55 minutes later,” Walker recalled. “I don’t even think the president of the United States gets covered live for 55 minutes.”

Almost all the candidates were surprised at Trump’s continuing support. “We knew that voters were clearly angry at President Obama and wanted significant change in the White House,” said Bradshaw, the Bush adviser. “Trump is a talented candidate who channeled their anger effectively. . . . Have we been surprised by his staying power? Yes. But has it changed who Jeb is and his belief in the type of candidate we need? No.”

Beyond the rhetoric, everything about Trump’s campaign style drew more attention to the candidacy and perhaps nothing more so than the Boeing 757 that carried him from rally to rally.

The plane carried gold-plated glamour along the campaign trail like no other competitor could. Trump invited journalists aboard for news conferences, or local politicians to put the squeeze on them for support. The cream leather chairs, with Trump’s crest woven into the headrests, hosted huddles with power brokers such as Sen. Jeff Sessions (R-Ala.) and fast-food dinners with his staff.

Trump, audaciously, landed his helicopter near the legendary Iowa State Fair in August. Just as Clinton was picking up her pork-chop-on-a-stick, sweaty fair-goers looked to the sky at the whirring sound of Trump’s helicopter approaching. A political Willy Wonka, sporting his red “Make America Great Again” cap, Trump offered kids rides on his helicopter. “Does anyone want to take a ride?” Trump asked them. “It’s nice, right?”

Trump continued his penchant for theatrical displays. Ahead of a raucous late-August rally in Mobile, Ala., he directed his pilots to thunder flamboyantly over a college football stadium packed with supporters before touching down. This was the Deep South, the heart of red America, and the unlikely candidate from Queens wanted to own it.

Bush’s super PAC tried to go toe-to-toe with Trump that day, renting a small airplane to fly over the stadium trailed by a banner that read, “TRUMP 4 TAXES. JEB 4 PREZ.”

Candidates playing by conventional rules, and with far fewer resources, found themselves at a huge disadvantage. By late summer, they began to fall away.

The first was Perry, the Texan who had run again in part to prove he was a better candidate than he had been in 2012. He had done that, but he was hobbled — more so than he had calculated — by the debate sponsor’s decision to split the field into varsity and JV sessions and particularly by an indictment for misusing his office. “The indictment needed to go away and I needed to be on the main debate stage,” he said. “Neither one of those happened.”

In some ways, Perry became an object lesson for the folly of trying to attack Trump directly. But he also admitted to miscalculations about the state of the Republican electorate. “I’ve been mad at Washington longer than anybody out there — and doing something about it,” he said, pointing to his record as governor.

But it was Trump — and, at that moment in early September, Carson and Fiorina — who were reaping the benefits of the anti-Washington anger.

“That’s my misjudgment,” Perry said. He added: “The electorate is really disgusted with Washington and the bullet goes through Washington and hits anybody that’s got any experience. They just lump us all into one.”

Perry’s departure came less than a week before the second debate, this one at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

Backstage or between commercial breaks at the debates, the candidates were collegial with one another. Their personalities in that mix were revealing; one candidate would quip to Priebus that if the RNC really wanted to raise money it would sell pay-per-view access to the green rooms.

Fiorina and Paul were known to be more serious outliers among the group. Rubio came across to some as scripted and Cruz alternated between being a loner and a social butterfly. Kasich occasionally was moody, Christie gregarious and chatty, and Trump particularly charming, endlessly in search of praise.

Heading into the Reagan Library debate, Trump knew his tussle with Fiorina might come up. A few days earlier, he was quoted in Rolling Stone magazine criticizing the appearance of her face: “Can you imagine that, the face of our next president?!”

Backstage before the debate, according to a person who observed the candidates and who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the private encounter, “He was really trying to work her.” It had little effect on Fiorina, who moments later would score one of her best applause lines with her steely retort to Trump. The debate propelled Fiorina in the polls for a few weeks, though she would not stay in the top tier for long.

“There’s a myth about Donald,” the same person said. “He doesn’t like one-on-one confrontation. He likes going on Twitter and taking off at somebody. Or he’s in another room and you’re 5,000 miles away and he bangs you. But when you’re face-to-face, he doesn’t like it. He’s not comfortable with it. He wants to be liked, and you could tell that backstage.”

Standing next to Fiorina that night was Walker. For the Wisconsin governor, the debate was a critical opportunity. Over the summer, he had seen his lead in Iowa evaporate, eclipsed by both Trump and Carson. He was in single digits in the state most critical to his hopes of winning the nomination and his campaign was under pressure to reverse the trend.

Through much of the evening, Walker was barely visible among the 11 candidates on the stage. After the debate, one of Walker’s sons made a telling observation.

“Dad, you only got a couple questions because all the questions were about attacks on the other candidates,” Walker recalled his son saying. “He said, ‘You don’t attack any of the other Republicans; of course, you didn’t get any questions.’ ”

Walker’s campaign was hobbled by more than the lack of visibility at the Reagan Library debate — mistakes by the candidate and what turned out to be profligate spending in the face of diminished resources.

But like Perry, Walker found that experience in office and a record of taking on fights prized by conservatives provided little boost in the face of the appeals of pure outsiders: “I think because there’s frustration, voters have said we’re going to go as far removed from that, which again is why you had not only Trump but at least for a while you had Carly and Carson be a part of this wave of interest out there.”

Within a week of the Reagan Library debate, Walker abruptly suspended his campaign. The decision, he said, came down to answering the question of whether he could make changes that would alter the trajectory of his candidacy. “If we can’t change so that we get more attention, then we don’t have a pathway to the nomination,” he said.

When Walker announced his suspension on Sept. 21, he said, “I believe that I am being called to lead by helping to clear the field in this race so that a positive, conservative message can rise to the top of the field. . . . I encourage other Republican presidential candidates to consider doing the same.”

None of the other candidates heeded Walker’s advice.

Autumn gave rise to a few rivalries that would linger into the New Year.Leading up to the Oct. 28 debate in Boulder, Colo., Bush and his team escalated their criticism of Rubio. At a closed-door strategy briefing, Bush’s advisers presented to donors a slide show, part of which detailed Rubio’s perceived vulnerabilities. They had two take-aways: Rubio has a lot of baggage and his relative inexperience relegated him a “GOP Obama.”

On the campaign trail, Bush was zeroing in on Rubio’s voting record, noting that he had missed more votes than any of his colleagues. Bush suggested senators who miss their work should have their pay docked. His son, Jeb Jr., played the part of aggrieved constituent: “Dude, you know, either drop out or do something.”

In their debate preparations, Rubio and his advisers knew what to expect. The moment came 21 minutes into the debate. “Because I am a constituent of the senator,” Bush said, scolding his one-time disciple, “I expected that he would do constituent service, which means that he shows up to work.”

Rubio counterpunched without missing a beat. “The only reason you are doing it now is because we are running for the same position, and someone has convinced you that attacking me is going to help you.”

In that instant, whatever air was left in Bush’s balloon seemed to fizzle out. Reporters in the spin room that night peppered campaign manager Danny Diaz with questions about whether Bush should quit the race.

The Bush team continued to believe that if it could convey to voters the candidate’s record of successes and reforms in Florida, its candidate would eventually win their support. This had been the focus of the pro-Bush super PAC’s fall advertising blitz. But to some voters, what had gotten through was not the Florida record but Trump’s incessant and unyielding mocking of Bush as “low energy.”

With fresh urgency, Bush headed to New Hampshire for a “Jeb Can Fix It” bus tour. He invited reporters onto his luxury coach, where Bush sat on a plush couch musing about his shortcomings.

“I’ve learned to accept the simple fact that I’m imperfect under God’s watchful eye,” he said one night. “I don’t have a self-esteem problem, and I don’t have an overstated-worth problem. . . . The adversity, I turn into opportunity. It’s an obstacle to jump over. It’s an opportunity to get better.”

Bush’s fall surprised some almost as much as Trump’s rise. “I expected Bush not only to have all the money, but also all the oxygen.” Kasich said. “But he just didn’t.”

Rubio, meanwhile, who had struggled all summer to raise money and gain meaningful traction in the polls, seemed set to soar. Soon, donors would sign on and endorsements would roll in. Looking back, Rubio said, “I’m not a big believer in this one pivotal moment that decides the whole race.” But if there were such a moment for him, the Boulder brawl was it.

The candidate who made the most of the Boulder debate was not Rubio, however. It was Cruz. The debate was a freewheeling and chaotic affair, and the confrontational line of questioning from the CNBC moderators set the candidates on edge. Republican base voters famously scorn the mainstream media, and Cruz pounced on the opportunity to turn on the moderators.

“This is not a cage match,” Cruz thundered at the debate. “You look at the questions: ‘Donald Trump, are you a comic-book villain?’ ‘Ben Carson, can you do math?’ ‘John Kasich, will you insult two people over here?’ ‘Marco Rubio, why don’t you resign?’ ‘Jeb Bush, why have your numbers fallen?’ ”

The live audience at the University of Colorado roared in approval. And over on Fox News Channel, the meter on pollster Frank Luntz’s focus group nearly went off the charts. Luntz said on the air, “I’ve been doing this since 1996. This is a special moment. I’ve never tested in any primary debate a line that scored as well as this.”

At the next debate, in Milwaukee on Nov. 10, Cruz would set his sights on Rubio. By the next morning, they had begun sparring over immigration policy, with each accusing the other of having once supported amnesty. Their squabbling would stretch into the new year.

Other candidates were left to fume at what they perceived was coverage almost totally dictated by the latest poll — and not always a reliable poll. Paul was among those most exasperated. His rallies, he said, were still well attended. “The frustrating thing is the lack of appreciation of what we’ve done,” Paul said. “The simplicity of news coverage is astounding, where they’ll poll 300 to 400 people, and that defines the story.”

AS FALL TURNED TO WINTER, outside events conspired to reshape the race. The terrorist attacks Nov. 13 in Paris and Dec. 2 in San Bernardino, Calif., spread fear across the country. More than anything, Republican voters were looking for strength.

Carson became an immediate victim. The mild-mannered surgeon hardly fit the profile of a wartime commander in chief. He stammered over foreign policy in interviews. His national security tutors leaked word that he didn’t know what he was talking about. And when Carson delivered a high-profile speech to the Republican Jewish Coalition, he repeatedly read “Hamas” in his speech notes and botched the name of the Palestinian-Islamist movement, pronouncing it as the ground chickpea dish “hummus.”

Before Paris, Carson had started to surpass Trump in some Iowa and national polls, but with the shift to foreign affairs his poll numbers plummeted. He made a last-ditch effort to arrest his standing, touching down in Jordan just after Thanksgiving to tour two Syrian refugee camps on a fact-finding mission. But it did not have the desired effect.

Frustrated, Carson gathered his advisers at his home in West Palm Beach, Fla., to discuss repairing how he was perceived on foreign policy. The downbeat session stretched on for hours, with Carson complaining to aides that he was being portrayed as foolish. “Obviously, going through a process like this is pretty brutal,” Carson would later say.

At the Dec. 15 debate in Las Vegas, he turned in another underwhelming performance. Soon, his campaign was engulfed in confusion and infighting. Carson didn’t know what to do to rescue his fleeting popularity with voters. He invited journalists from The Post and the Associated Press to his home two days before Christmas to signal a staff shake-up. No one’s job was safe, he warned.

“The key thing for me is just going to be not changing,” Carson said. “Everybody wants you to change. They say, ‘If you do this, it’ll be better.’ But that’s what politicians do. That’s what they try to do in order to get elected. I’m not trying to change in order to get elected.”

On the last day of the year, campaign manager Bennett and other top officials resigned from the Carson campaign.

The Paris and San Bernardino attacks persuaded other candidates that a shift to life-or-death issues of national security would expose Trump as unworldly and unknowledgeable. But once again, he defied the norms of politics.

The policy pronouncement came over by email on Dec. 7, Pearl Harbor Day, at 4:16 p.m.: “Donald J. Trump Statement on Preventing Muslim Immigration.”

Trump called for a “total and complete” ban on Muslims entering the United States, at least temporarily. His statement cited research that he said showed that large segments of the world’s fastest-growing religion were rooted in hatred and violence.

The proposal defied a call for tolerance toward Muslims that President Obama issued less than 24 hours earlier from the Oval Office. It drew condemnations from leaders around the globe as well as his rival candidates. “Donald Trump is unhinged,” Bush tweeted.

Finally, Trump had crossed a bridge too far. Or so went the instant analysis — once again. But that night in South Carolina, campaigning aboard the USS Yorktown, Trump defiantly read his proposal. Banning Muslims was “common sense,” he said. “We have no choice. We have no choice.”

His crowd rose to its feet. There were cheers and hoots and loud applause. In the days to come, Trump’s poll numbers climbed higher still. Republican primary voters, it turned out, liked what he had to say.

The Muslim comment seemed to spur Bush to action. In the year’s final debate, he confronted Trump more vigorously than ever, delivering a performance that seemed to rejuvenate him. He continued to carry the attacks on Trump through the rest of the year with the hope that in the upside-down world of the Republican race, no one was truly out of the running.

“This is not something that is new,” adviser Bradshaw said of Bush’s aggression. “Trump’s comments keep getting more outrageous. He felt it was incumbent on him to push back. He [Trump] is not our path to the White House.”

Bush told CBS’s John Dickerson in late December that he had “hated” being the front-runner and now felt unleashed to run freely. “It is a little liberating to be able to post up against a guy who is not qualified to be president,” he said.

Bush’s candidacy now stood for something else, however, which was the epic failure of super PAC dollars to change the dynamic of the Republican race in 2015. Right to Rise, Bush’s super PAC, spent tens of millions of dollars through the fall and early winter months while Bush’s poll numbers continued to sag. But no other candidate super PAC was having any real success, either.

On New Year’s Eve, Trump took to Twitter to observe: “.@JebBush has spent $63,000,000 and is at the bottom of the polls. I have spent almost nothing and am at the top. WIN!”

No final verdict was possible on the power of the super PAC until the voters were heard from in 2016, but in 2015 they were the dogs that didn’t bark.

Trump wasn’t the only presidential hopeful trying to exude strength after San Bernardino. For Christie, who had toiled for months in relative obscurity searching from one New Hampshire town hall meeting to next for a comeback, terrorism became his lucky strike. Suddenly, the tough, straight-talking former prosecutor from New Jersey was a hot draw.

At town hall-style meetings stretching two hours long, grown men and women were reduced to tears as Christie talked about the five hours on Sept. 11, 2001, when he didn’t know if his wife, Mary Pat, who worked in Lower Manhattan, had died with the fall of the Twin Towers.

Christie also stressed that, as a former U.S. attorney in New Jersey who dealt with issues of terrorism after 9/11, his credentials stood alone. Sitting down for an interview one chilly December night in Wolfeboro, N.H., Christie said: “I personally know all the tools that are available and have used them. No one else on that stage has done that. They’ve just heard about it from other people. It’s the difference between playing in a sport and being a spectator.”

By year’s end, there was a palpable sense of unease about the future — fear of possible terrorist attacks, distrust of institutions and political leaders, economic anxieties amid the recovery and lower unemployment, and confusion about what verdict the voters would deliver in November.

Analysts looked for parallels for the year just ended. Was this like 1992, a year of anger at government when a third-party candidate by the name of Ross Perot captured nearly a fifth of the national vote? Or 1948, with two major-party nominees and independent candidates from the left and right? Or the period in the late 1960s and early 1970s when the racially based rhetoric of George Wallace struck a populist chord?

Geoff Garin, a Democratic pollster who advises a pro-Clinton super PAC, said: “I think it’s unique to our times. It’s very much a product of the economic moment, this combination of a world of post-Citizen’s United [the Supreme Court case that helped give rise to super PACs] and post-Great Recession. . . . I definitely think what we’re going through now is deeper and darker than anything we’ve gone through in our politics for a long time.”

The Democratic nomination contest still falls along more conventional lines, with a strong front-runner in Clinton backed heavily by the establishment and an insurgent challenger in Sen. Bernie Sanders (Vt.) powered by an energized progressive base.

The real turmoil is inside the Republican Party, now clearly split and heading for a potentially decisive clash between its warring factions.

Whatever lies ahead, the assumptions candidates and their strategists carried with them as the year began were mostly blown apart by what happened, including the possibility that Trump could become the Republican nominee. Among Trump supporters, there is a belief that the political class doesn’t know what’s coming. Party leaders still heavily discount that possibility, but they no longer rule it out.

“I’m not one of these people that think that Donald Trump can’t win a general election,” said Priebus, the RNC chair. “I actually think there is a huge crossover appeal there to people that are disengaged politically that he speaks to. . . . Donald Trump taps into the culture. Some people in politics don’t get it, don’t understand it, are frustrated by it. It doesn’t matter. He does.”

The struggles of the establishment candidates to slow down Trump and Cruz, who by year’s end was surging in Iowa, led some party figures to think about a saving grace. In late December in Boston, Romney said he still encounters Republicans trying to draft him. “Every day I get a call or letters,” he said. “I go to church, I get harangued at church. ‘Oh, you’ve got to run!’ ”

“Look,” Romney added, “I had one person who was running for president, and I won’t give you the name . . . called me and said, ‘I hope you don’t close the door. We may need you.’ That’s a person running for president. A candidate. A Republican. I’m not giving it a second thought.”

One other thing has changed: At the time Trump entered the race and began to defy the conventional rules of past campaigns, there was a sense in the camps of some of his rivals that he had created an alternate universe that ran parallel to the more traditional path of politics. It was there to observe but not necessarily understand or manage. Now many have come to see that they all are operating inside that alternate universe.

They are trying to adapt as best they can. Rubio’s rhetoric is edgier than it was before. Christie has used over-the-top language to attack Congress and especially Obama, whom he described as a “feckless weakling” at the last debate of the year.

For someone like Cruz, a terrain defined by anger is a welcome development. His campaign was shaped from the moment he arrived in Washington as one that would find its most fertile ground among those most disaffected with the elites and the Washington establishment.

“I’m a big believer in politics that truth will out,” Cruz said. “You run as who you are. Indeed, the candidates who often tend to do the worst are those who can’t figure out who they are and who run one day as a conservative and one day as a moderate and end up getting the support of neither.”

For someone like Rubio, the environment has presented unexpected challenges. How does a candidate who built his campaign around a positive and hopeful message navigate a campaign in which fear and anger have become the guiding emotions?

Asked why he believed his approach could win the day in such an environment, Rubio said, “We are a hopeful and optimistic people and we have a lot to be optimistic about if we do what needs to be done. So I would say my campaign is realistic but optimistic.” But he went on to say this: “I recognize people’s frustration and you’ve got to speak to that. If they don’t believe you’re in touch with what they’re feeling in their lives, there’s no way they’re going to make you president.”

By the time 2015 closed, more candidates had quit the race. Jindal exited in mid-November, and Pataki followed him in December. When he quit, Jindal noted how the environment favored someone like Trump over more traditional candidates. Saying he had tried to offer policy ideas to the voters, he told Fox News anchor Baier, “Given this crazy, unpredictable election season, clearly there wasn’t an interest in those policy papers.”

Candidates far down in the polls hold out hope that the voters will prove to be unpredictable, as ever. “When people ask that question about surprise, they assume we know something about the election,” Paul said. “We haven’t had an election. We have polls and things, but I don’t think we’ll know anything until the voting begins.”

As Kasich said, 2016 “could be a year where things could be absolutely normal because right now they appear abnormal. There’s no voting yet.”

Santorum said Trump’s suffocating presence has slowed the normal rhythms of the campaign, in which candidates rise, are exposed to scrutiny and either prosper or lose altitude. “It’s more incremental,” he said. “They’re not getting the attention that leads to a higher spike and leads to a faster decline. Trump has been a depressant factor on this rise and fall, and it’s stretched it out.”

Santorum has been kept in the shadows, but is he frustrated? “Four years ago, I was more frustrated than I am now,” he said. “I actually understand this. I understand the fixation [with Trump]. I get that. What I’m waiting to see — and this is the valuable role Iowa plays in the process — is whether Iowans who go to caucuses are going to continue on this trek; or are they going to take a step back and say, ‘We’re going to regress to the norm?’ ”

As Election Year begins, the answer to that question seems no more predictable than it was last June 16.

Dec. 28-30, 2015

It’s the week after Christmas and the first contests are little more than a month away. In Iowa and New Hampshire, voters brave nasty snow and difficult roads to question the candidates.

Chris Christie is in Muscatine, Iowa, and goes straight for the serious stuff. Terrorism. ISIS. That shooting at a center for the developmentally disabled in San Bernardino? It could happen anywhere — and though he doesn’t say Muscatine, everyone knows that’s what he means. Marco Rubio is 70 miles up the road in Clinton, an aptly named starting point for his “Out With the Old, In With the New” tour of Iowa. The country is heading toward ruin, and this hopeful son of immigrants wants to save it.