State Ups Passing Standards on Public School Exams

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/STARR-Test.jpg)

It will get harder for Texas public school students to pass standardized tests this year, Texas Education Commissioner Michael Williams announced Tuesday, ending speculation that new, higher standards might be delayed. But Williams said the state will ease into the tougher passing standards more slowly than originally planned.

Since they were launched three and a half years ago, scores have remained flat on the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness, or STAAR, exams, prompting some to guess that the state would again delay upping the number of questions students must answer correctly to pass.

The lag had already prompted Williams to delay implementation of the stricter standards, which were set to take effect two years ago.

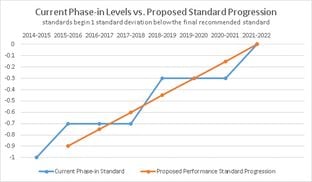

But Williams unveiled a more gradual phase-in of the stricter standards to replace a stair-step approach he announced just last year that would have implemented more dramatic increases this year and again in 2018-19 and in 2021-22.

The so-called "standard progression approach" is designed to be gentler, Williams explained in a statement Tuesday, saying it "is intended to minimize any abrupt single-year increase ... for this school year and in the future."

The standards will progressively increase until the 2021-2022 school year when students will be required to perform at levels of "postsecondary readiness."

Williams' announcement was not unexpected. In remarks at a conference in Austin Saturday, Williams confirmed the increased standards, which had been set to take effect under a 2014 plan that delayed them for the 2014-15 school year.

Citing his remarks, the Texas Education Agency said in a statement this week that “the announced move should not have been a surprise to superintendents because the state has been at Level I for the past four years and the Commissioner had already advised several months ago that the state would be moving to the next higher standard."

Tuesday's announcement confirmed the launch of the Level II standards.

Still, critics said the move won't do anything to help Texas students whose performance has not improved on the harder exams even with a laxer passing standard.

"I think it’s really kind of almost cruel to raise passing standards at such a time," said Theresa Trevino, president of Texans Advocating for Meaningful Assessment, a statewide grassroots organization that has successfully pushed for standardized testing reforms.

Texas students in grades 3 through 8 must take two or more subject-specific exams under the testing regime launched in spring 2012. STAAR is considered more difficult and rigorous than its predecessors.

Under the high-stakes system, some students are expected to pass their exams before advancing to the next grade level, and high schoolers are expected to pass five end-of-course exams (15 before lawmakers opted to reduce it) before receiving a diploma, although lawmakers created a major exception to that requirement earlier this year.

Passing standards on exams administered last year varied by grade and test.

That will remain the case under the new passing standards, said TEA spokeswoman Debbie Ratcliffe. "Students will have to answer one to two questions more correctly to pass” under the tougher requirements, she said.

"If we (had) stuck with our previous phase-in plan, they would have had to answer on average four more questions correctly," she said, explaining that the agency thinks teachers and students have had enough time to adjust to the new regime.

"You can’t increase the standards without knowing that potentially the passing rate is going to decline, but hopefully with that extra year of instruction the scores will go up," she said.

On the reading exam administered last spring, eighth graders had to answer 28 of 52 questions correctly to pass — less than 54 percent — while fifth graders taking the math exam had to answer 23 of 50 questions correctly or 46 percent.

Student performance on state standardized tests is a focus of a long-running school finance lawsuit involving more than two-thirds of Texas school districts pending before the Texas Supreme Court. During the trial, lawyers for the state said poor performance on the state exams the first time around was to be expected as schools adjusted to STAAR. School districts argued that they had not received enough resources to meet the new, more rigorous standards.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Kiah.jpg)