Skinner, Running Out of Time, Awaits DNA Ruling From Skeptical Court

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/SkinnerDNA.jpg)

Hank Skinner has been pleading with the state since 2001 — to no avail — to test DNA evidence he believes will prove his innocence. On Wednesday, he is set to walk into the execution chamber in Huntsville to face the ultimate punishment for three murders that he maintains he did not commit.

“I have never had a case where we had to fight 10 years to get DNA tests,” said Nina Morrison, senior staff attorney at the Innocence Project, who has worked on hundreds of cases. “This kind of protracted litigation is extremely rare these days.”

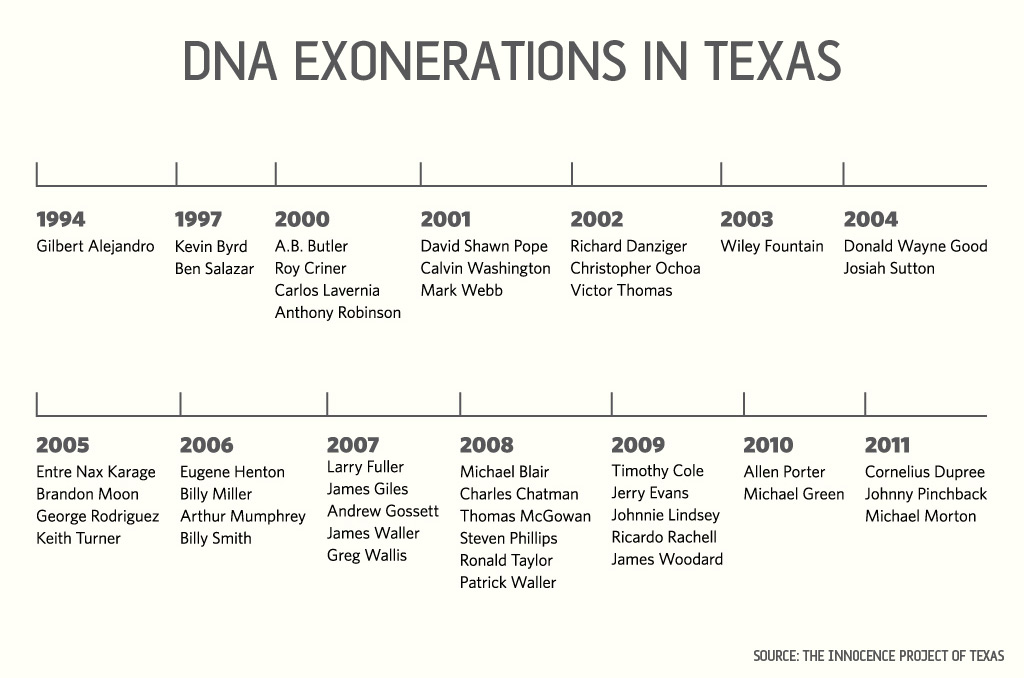

Skinner was convicted in 1995 of murdering his live-in girlfriend, Twila Busby, and her two sons in their home in the Panhandle town of Pampa. Texas — and most other states — didn’t have a post-conviction DNA testing law then. But since Skinner has been in prison, Texas has developed one of the strongest post-conviction DNA laws in the nation, and 45 inmates have been exonerated based on the results of biological testing.

As the Texas Legislature has expanded access to post-conviction DNA testing — since the original law was passed in 2001, legislators have loosened restrictions to DNA testing three times — Skinner has filed new appeals. Each time, he has been rebuffed. Now, for the fourth time, he is on the verge of execution. He is awaiting a court decision on whether the most recent law expanding post-conviction DNA testing, passed earlier this year, will be applied to him.

Texas approved its first post-conviction DNA testing law in 2001 on the heels of two high-profile cases.

In 1990, Roy Criner was convicted of aggravated sexual assault. Tests later showed his DNA did not match semen or a cigarette butt found at the crime scene. Two lower courts overturned Criner’s conviction, but the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals upheld it.

In a PBS Frontline interview, Sharon Keller, presiding judge of the appeals court, the state’s highest criminal court, said DNA evidence was not enough to prove Criner’s innocence. “The state would have explained that the girl was promiscuous, and might have shown that she'd had sex with different people,” Keller said.

Eventually, then-Gov. George W. Bush pardoned Criner.

The other case involved Ricky McGinn, convicted in 1995 of raping and killing his 12-year-old stepdaughter. When his execution date came up in June 2000, McGinn was pursuing new DNA tests. At the time, Bush and then-Lt. Gov. Rick Perry were out of the state and Sen. Rodney Ellis was acting as governor. The Houston Democrat postponed the execution to allow for the analysis, and he called for a post-conviction DNA testing law.

“While I am reluctant to second guess the verdict of a Texas jury and our courts, we must be willing to take every step possible to ensure that justice is done,” Ellis said at the time.

The test results didn’t clear McGinn and he was executed in September 2000.

The following year, Ellis worked with other lawmakers, including Lubbock Republican state Sen. Robert Duncan, who wrote the bill, to pass a comprehensive post-conviction DNA law. It spelled out conditions under which inmates could get access to testing and established rules requiring law enforcement to preserve DNA evidence.

Opponents of the DNA testing bill, including some prosecutors and prison officials, worried that it would cause inmates to file a flood of requests. To address that concern, lawmakers adopted strict standards that required inmates to demonstrate not only that the results of DNA tests would prove their innocence but also would have prevented them from even being prosecuted.

Some DNA evidence was presented at Skinner’s 1995 trial and it showed that his blood was at the crime scene. But Skinner said the blood was the result of cutting his hand on broken glass left behind by the violent assault on his girlfriend and her sons. Skinner maintains that during the killings he was unconscious on the couch, intoxicated from a mixture of codeine and vodka (a toxicology report confirmed that he had high amounts of both in his system).

But because his lawyers feared the results might be incriminating, they did not seek testing on a rape kit, biological material from his girlfriend's fingernails, sweat from a man’s jacket, a bloody towel or knives from the crime scene.

After the 2001 law passed, Skinner filed his first request for testing on several pieces of evidence asserting that DNA evidence on those items could prove that another man committed the crime.

In 2003, the state Court of Criminal Appeals denied Skinner’s request, arguing that he did not meet the standards for testing, citing, among other issues, the requirement that he demonstrate that he wouldn’t have been prosecuted based on the new DNA results.

“That’s essentially an impossible standard to meet,” said Rob Owen, Skinner’s attorney and a clinical law professor at the University of Texas School of Law.

Mike Ware, supervisor of the innocence project at Wesleyan School of Law in Fort Worth who previously worked in the Dallas County district attorney’s office, said many inmates experienced the same stumbling block. The statute allowed district attorneys to block testing by telling courts that DNA results would not have prevented them from prosecuting the inmate.

Lawmakers began to realize it was an unreachable standard, too, said state Rep. Scott Hochberg, D-Houston.

“Despite the fact that we had worked very hard and passed the first bill, nothing happened,” he said. “It resulted in no changes at all.”

In 2003, Hochberg sponsored a bill that, among other things, eliminated the requirement that the DNA results would have prevented prosecution.

“We had to create a standard and make that standard achievable but not wide open,” he said.

The change allowed Billy James Smith, who had been convicted of raping a woman at his Dallas apartment complex, to obtain DNA testing the courts had previously denied. It proved Smith’s innocence, and in 2006 he was exonerated.

The next change in the law came in 2007, when lawmakers told courts they couldn’t deny post-conviction DNA testing solely because an inmate had pleaded guilty or confessed. “Some defendants enter pleas of guilty as business decisions, for lack of a better way to put it,” Ware said.

That change helped to free Eugene Henton. He had pleaded guilty in 1984 to a rape he did not commit and served 18 months of a four-year sentence. A decade later, Henton was arrested on unrelated drug and assault charges. “The prosecutor hammered him with the fact that he was a convicted violent sex offender,” Ware said. The jury gave Henton a 40-year sentence.

While he was in prison, Henton requested and received DNA testing on a rape kit that revealed another man was responsible for the 1984 rape. Henton’s sentence on the drug and assault charges was vacated and in October 2007, he was released.

Skinner filed a second request for DNA testing in 2007, citing, among other arguments, the expansions of the law. The Court of Criminal Appeals again denied the motion. In addition to asserting that new DNA tests wouldn’t prove his innocence, the court said he should have requested the testing at his original trial.

Less than an hour before his scheduled execution in March 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court intervened. After a subsequent hearing, the high court sent Skinner’s case back to a lower federal court to decide whether Texas courts unconstitutionally applied the state's post-conviction DNA law.

Before the federal court ruled on that question, lawmakers this year made yet another change to the DNA law. The original 2001 legislation allowed testing only in cases in which DNA tests were not conducted during the original trial because the technology was unavailable or for some other reason that was not the fault of the defendant. Ellis, who is chairman of the Innocence Project, sponsored a measure that repealed those restrictions.

Based on that change, Skinner filed a new request in September. Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott’s office has opposed it — because the state appeals court has already twice denied testing. The “… CCA found that no exculpatory test results could possibly prove Skinner’s innocence,” the state’s motion said.

In an interview this week, Ellis said he doesn’t understand how the court could continue to deny Skinner’s request, which he said fits squarely within the category his recent legislation aimed to address.

But last week, without explanation, the trial court in Gray County did just that. Skinner’s lawyers have appealed yet again, hoping the state Court of Criminal Appeals will agree that the Legislature has removed enough barriers to finally allow DNA tests before he is executed.

“The case for DNA testing for Mr. Skinner has been made much stronger,” Owen said. “Common sense really seems to cry out for it.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/grissom-brandi.jpg)