Experts Say Morton Case Shows Justice System Still Needs Reform

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/MortonAndMother.jpg)

Not long after his mother was murdered, 3-and-a-half-year-old Eric Morton began to tell his grandmother what he had seen that terrible day.

“Mommy’s crying. She’s — Stop it. Go away,” his grandmother said he told her. She asked why his mother was crying.

“’Cause the monster’s there,” Eric said.

Gingerly, she pressed for more details.

“He hit Mommy. He broke the bed,” her grandson said.

“Is Mommy still crying?”

“No, Mommy stopped.”

Finally, his grandmother asked the question she was most dreading: “Was Daddy there?”

“No,” he said. “Mommy and Eric was there.”

The next day, she called the lead sheriff’s investigator to tell him what the boy had said and that she no longer suspected that her son-in-law, Michael Morton, had killed her daughter, Christine. She urged the investigator to abandon the “domestic thing now and look for the monster.”

Days after Christine Morton’s badly beaten body was found in her bed in August 1986, someone used her credit card in another city. And a check was cashed with her forged signature.

The sheriff’s investigators who saw Michael Morton as the prime suspect had that information and a transcript of the grandmother’s call. But when he was on trial facing a life sentence for murder, his defense lawyers knew none of it.

A quarter-century later, after six years of fighting for DNA tests that now almost certainly will result in the reversal of Morton’s conviction, his lawyers say prosecutors withheld this and other exculpatory evidence from his original defense lawyers and from the trial judge despite orders to turn it over. In court filings, the prosecutors have denied accusations of wrongdoing.

Since 1994, DNA tests have exonerated 44 Texas inmates, according to the Innocence Project of Texas, based in Lubbock. In the wake of those cases, Texas lawmakers have made significant reforms to criminal justice procedures to help prevent wrongful convictions. But defense lawyers and Morton’s advocates argue that under antiquated Texas discovery laws, the alleged injustices that robbed him of 25 years could still happen.

“Michael’s struggle would be in vain if we didn’t think soberly about what went wrong in his case and how it can be fixed,” said Nina Morrison, senior staff lawyer for the Innocence Project, which worked on Morton’s case and which is based in New York.

The landmark 1963 United States Supreme Court decision Brady v. Maryland requires prosecutors to provide defendants with exculpatory evidence — information that could prove their innocence. But Texas law does not define “exculpatory evidence,” and there is no statewide standard; prosecutors or trial judges typically decide what qualifies. State law does not require prosecutors to automatically share with defense lawyers even basic information like police reports and witness statements.

Many prosecutors, including district attorneys in Dallas, Houston, Fort Worth and Austin, have adopted open-file policies that require their lawyers to share all their evidence with the defense.

Tarrant County adopted its policy in the 1970s, said Jack Strickland, a former defense lawyer who is deputy chief in the district attorney’s criminal division.

“The more serious the case, the more serious the potential consequences,” Strickland said. “We wanted to have as much transparency as we could because of the stakes involved.”

In 2010, the Timothy Cole Advisory Panel, a committee created to recommend new laws that might prevent wrongful convictions, urged legislators to adopt a mandatory statewide discovery policy. Seven of Texas’ first 39 DNA exonerations involved evidence suppression or other prosecutorial misconduct, according to the panel’s report.

The panel — named after a Lubbock man charged with rape who died in prison before exonerated him — told lawmakers that Texas should follow the example of other states that require lawyers on both sides to share information in criminal cases.

“We have 254 counties in this state, and potentially 254 ways of deciding what the defense will see prior to trial,” said Kathryn Kase, executive director of the Texas Defender Service and a member of the Tim Cole panel.

Since 2007, lawmakers have proposed more than a half-dozen measures that would have expanded access to discovery. None have passed.

Sen. Rodney Ellis, D-Houston, who is also chairman of the Innocence Project, said prosecutors had worked to stymie the measures. The opposition, he said, reflects an attitude among many Texas prosecutors that a conviction equals a win.

“The role of the prosecutor is to discover the truth,” said Ellis, who is also a lawyer. “But oftentimes there’s more interest in getting a conviction.”

He pointed to a recent decision of the Texas District and County Attorneys Association to honor a prosecutor who had intervened to stop a court hearing meant to examine whether Cameron Todd Willingham was innocent. Willingham was executed in 2004 for the 1991 arson fire that killed his three young daughters. Numerous scientists have since discredited the evidence used to convict him.

“I think the Morton case is going to be a catalyst for moving some of those reforms forward,” Ellis said.

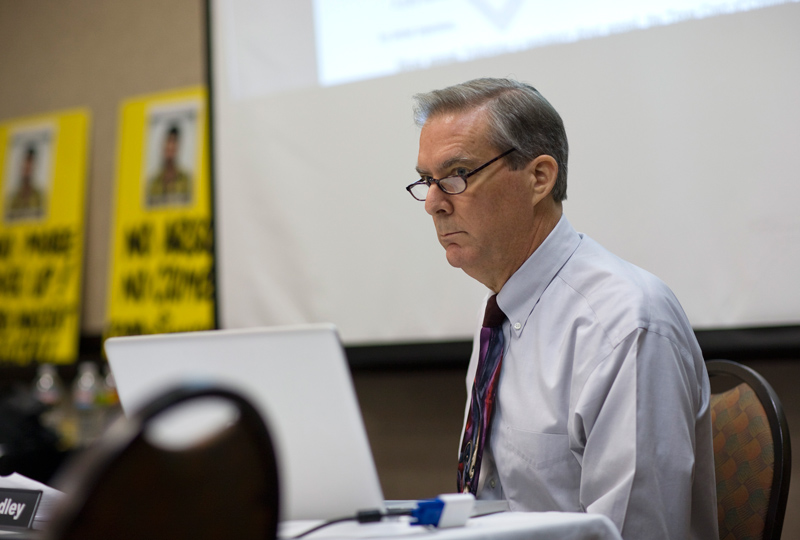

John Bradley, the Williamson County district attorney, whom Gov. Rick Perry appointed in 2009 to lead an independent panel charged with reviewing forensic evidence in criminal cases, was an ardent opponent of re-examining the Willingham case.

Bradley has also most recently been in charge of the Morton prosecution. For more than six years he opposed the DNA testing that led to Morton’s release from prison last week and an agreement by prosecutors to seek to have his conviction overturned. He also resisted efforts by Morton’s lawyers to use public-information laws to gain access to evidence in the original prosecutors’ files.

Bradley publicly derided the lawyers’ efforts to prove that a “mystery killer” killed Christine Morton.

Bradley said last week that he had resisted efforts to test the DNA for good-faith reasons that he could not discuss because of the continuing investigation.

Prosecutors, though, have not been the only ones to object to expanding discovery, said Rob Kepple, executive director of the Texas District and County Attorneys Association. Defense lawyers, he said, have objected to legislation that would also require them to turn over evidence to prosecutors.

What is more, Kepple said, a new discovery law would not have prevented the kind of misconduct alleged in the Morton case. If a prosecutor or investigator decides to withhold key information even in the face of the Brady rules that already require its release, he said, a new state law will not spur their compliance.

“If somebody didn’t play fair back then,” he said, “I’m not sure exactly what law we change today to address it.”

Indeed, in Tarrant County, where the open-file policy has long been in place, Strickland said there had been two instances in which a prosecutor suppressed evidence to help secure death penalty convictions.

The same lawyer worked on both cases and is no longer employed at the Tarrant County District Attorney’s Office, he said.

“You can’t discount the possibility that somebody is going to come in and make a conscious decision to do something wrong,” Strickland said.

Despite that aberration, he said, the open-file policy has only helped Tarrant County.

It is an advantage for defense lawyers, since they can quickly access information they need to represent their clients, he said, and it helps prosecutors because they do not have to spend time and money fighting in court over access to evidence.

“It’s a downside only if you think winning is everything,” Strickland said. “And winning is not everything.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/grissom-brandi.jpg)