Cost of Procedures Varies Widely by Hospital, Area

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/MedAppArt_Emily.jpg)

The cost of common medical procedures paid for by Medicaid — the joint state-federal health care program for indigent children, the disabled and the very poor — varies dramatically from hospital to hospital and region to region, according to a Texas Tribune analysis of claims by and payments to hundreds of hospitals across the state.

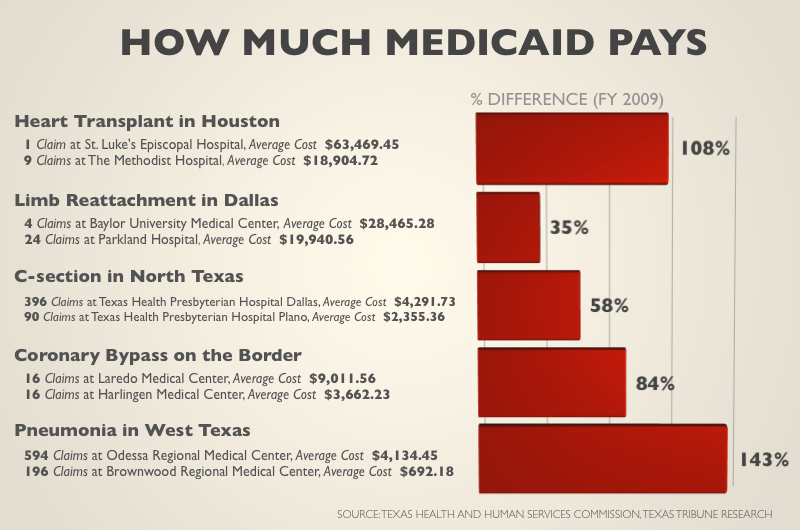

A routine delivery at St. Luke’s The Woodlands Hospital costs Texas Medicaid twice as much as at Christus St. Catherine Hospital in Katy, just 50 miles away. The Laredo Medical Center bills Medicaid nearly $5,500 more for a coronary bypass than the Harlingen Medical Center, though both hospitals are along the Texas-Mexico border.

The disparity in pricing is the result of a payment formula that gives each Texas hospital its own individual rate, a system that appears to be losing support in the Legislature. State health officials, seeking ways to curb Medicaid costs and address the concerns of hospitals on the lower end of the payment spectrum, have proposed a single base rate for all hospitals — with a variety of allowances for expensive-to-operate facilities like children’s hospitals and state-owned teaching hospitals. Such a formula, they say, would save Texas, which faces an enormous budget shortfall, an estimated $74 million over the next two years — and up to $2.8 billion if lawmakers set the rate at the bare minimum and go without the allowances.

Hospitals are strongly divided on the change, depending on what it costs to operate their facilities and which services they provide. Some say an average rate is unworkable, because it cannot reasonably take into account all the hospital-specific factors that eat away at their bottom lines. Almost all of them say the bare minimum rate would be catastrophic.

The rate “should stay hospital specific, to give recognition to those hospitals offering a greater scope and level of service,” said Joel T. Allison, president and chief executive of the Baylor Health Care System, adding that Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas has to account for the costs of trauma and neonatal units, as well as transplant, oncology and graduate medical education programs.

Other hospitals support an average rate so long as lawmakers are thoughtful about the allowances and make some consideration for cost-of-living increases and capital expenses.

“It doesn’t seem reasonable to see huge differences within a geographic area,” said Ron J. Anderson, president and chief executive of Dallas’ Parkland Health and Hospital System, which, in addition to its trauma, burn and neonatal units, is a teaching hospital, has large volumes of charity patients who require social workers and translators, and is building a new hospital. “If they would take those things into account, along with some kind of reasonable wage index, this isn’t a bad reform.”

The current Medicaid payment system gives the largest average reimbursements to hospitals that have complex costs, the Tribune analysis shows, like those that predominantly treat children, teach medical residents or are trauma centers.

But it also rewards private suburban hospitals that perform fewer procedures with higher average payments. Medium-sized hospitals in East Texas, West Texas and along the border tend to get lower average reimbursements, as do large county hospitals that have high volumes of patients.

Not including outliers — the expensive, complicated procedures that skew the data — the average appendectomy in fiscal year 2009 cost Medicaid $2,200 at a hospital in El Paso, versus $6,200 at a Houston children’s hospital. Having a pacemaker installed in Laredo cost $600, compared with $8,500 in Harris County’s nonprofit hospital system. And a baby with complications from prematurity cost $10,000 in a high-volume Beaumont medical center, compared with $48,000 at a suburban Houston hospital.

Prices even varied within the same hospital system. In fiscal year 2009, the average Caesarean section cost $4,300 at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas and $2,400 at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Plano — which Stephen O’Brien, the system’s spokesman, said is because the Plano hospital has been “grossly underpaid by Medicaid for many years.”

The formula Medicaid currently uses to reimburse Texas hospitals is anything but straightforward. Every medical condition or procedure, from pneumonia to installing a pacemaker, has its own “weight,” or relative value. To determine how much the state pays, this weight is multiplied by a hospital-specific rate called a “Standard Dollar Amount,” or SDA, which is determined by the state’s Health and Human Services Commission.

The SDA takes into account all of a hospital’s costs, from the percent of uninsured patients to the salaries it pays. Even after all of that math, hospitals are not paid the full amount; Medicaid reimburses them at about 60 percent of their costs.

State health officials say calculating a different SDA for every hospital in Texas is a mathematical mess that does not reward efficiency or performance and leads to large disparities in reimbursements.

“It has become very obvious that there is a wide range in average costs for hospitals,” said HHSC Commissioner Tom Suehs. “And we cannot explain it all.”

Suehs proposes setting the same SDA for all Texas hospitals, then giving extra allowances to hospitals that have high costs because of services they provide. Hospitals that have trauma and burn centers, specialize in cancer treatment, predominantly treat children or have large populations of uninsured patients would likely qualify for a boost, he said.

That would level the playing field for hospitals forced to run a lean, efficient operation, said Susan Turley, the chief financial officer at Doctors Hospital at Renaissance in Edinburg, where 80 percent of patients are covered by Medicaid or Medicare.

“Speaking as a taxpayer, why should I pay $2,000 for a surgery in South Texas and $7,000 for that same surgery in Dallas?” Turley asked. “Hospitals will be incentivized to provide efficient care. And those that already are won’t be penalized.”

Many lawmakers seem to agree. “It seems like we’re just incentivizing hospitals to drive their costs up because then they get more money from us,” state Sen. Tommy Williams, R-The Woodlands, said in a recent Senate hearing

But hospitals carry a lot of political heft — and many fear what losing individual rates could mean. John Hawkins, senior vice president of governmental relations with the Texas Hospital Association, said lawmakers should not make any rash moves to fill the budget hole, and should instead consider how to reform the payment system over the interim.

“It’s going to take some time to make sure we get it right,” he said. “Let’s just not try to do it over the next two months.”

Data gurus Ryan Murphy and Becca Aaronson contributed to this report.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Ramshaw-Close.jpg)