The Fire Next Time

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/TX-Forensic-JohnBradley004-TP.jpg)

Under the leadership of Williamson County District Attorney John Bradley, the Texas Forensic Science Commission has waged a masterful war of attrition in the Cameron Todd Willingham matter: Stall long enough, and public interest in the internationally controversial capital punishment case — along with the political liability for any missteps — will fade away. But the commission’s latest delay, while pushing the resolution of the Willingham investigation securely after the general election, comes against Bradley’s wishes and could represent a sea change on the board that until now has resisted making any broader inquiries into the state’s arson convictions.

Bradley, appointed by Gov. Rick Perry to head the commission in October amid questions over whether Willingham was prosecuted on the basis of faulty evidence, says it’s representative of something else entirely. He believes the commission, whose members are appointed by the governor, lieutenant governor and attorney general, has become a political football, subject to “endless waves of ongoing outside improper influence” from death penalty opponents and groups with “agendas outside of forensic science.”

Going into Friday’s hearing on the arson investigation used to convict Willingham, whom the state executed in 2004 for allegedly setting a fire that killed his three young daughters, the commission appeared poised to clear fire analysts of any professional misconduct. Then, during testy exchanges with Bradley, members balked at adopting a draft report he circulated prior to the meeting. The report said that while arson science has changed since Willingham’s 1992 trial, the fire experts who provided evidence for the state were using acceptable techniques at the time and did not have access to scientific advancements that could have changed their conclusions. (Download the report above.)

“It sounds as if the panel is suggesting the investigators were abiding by the science," objected commissioner Sarah Kerrigan, who said she believed that while the fire analysts may have followed their professional guidelines, those guidelines weren’t necessarily as advanced as existing science.

What existing science was at the time is significant. If the commission determines that evidence in the Willingham case was not collected using up-to-date science, it could implicate the State Fire Marshal’s Office, which has stood by investigators’ conclusions on Willingham through nine appeals and his eventual execution. It could also open the door for appeals in the cases of the estimated 750 people currently serving time on arson convictions in Texas.

But when Kerrigan said she wanted more time to question a panel of experts about the science available to the investigators who testified against Willingham, Bradley became visibly peeved and accused commissioners of “shirking their duties.” A second commissioner, Garry Adams, echoed Kerrigan’s concerns, saying he too was "not completely convinced the science was not available" to the analysts. Adams said he wanted to look at the manuals and materials those investigators relied on before making a decision, but Bradley said that information wasn’t available. “We've previously asked [the experts] for those things,” he said, “but if you want, we can waste another meeting getting those non-answers.”

Despite Bradley’s exasperation, commissioners pressed on, expressing concern that out-of-date science may have been routinely used in past arson investigations — an issue that state Sens. Rodney Ellis, D-Houston, and Juan "Chuy" Hinojosa, D-McAllen, urged commissioners to take up in a letter they sent in advance of the meeting. Commissioner Nizam Peerwani, the Fort Worth medical examiner, called for a review of the fire marshal’s office outright, saying “somebody needs to go back and look at all the other cases they investigated.”

"Licking their chops"

Answering questions via e-mail after the meeting, Bradley said he did not believe the commission had the legislative authority “to make global statements about alleged systemic problems” in arson cases. “Criminal defense lawyers and plaintiffs’ attorneys must be licking their chops over that issue,” he wrote.

In his e-mail, Bradley also complained about the intense public scrutiny the commission has received, calling it the equivalent of “being on reality TV.” “The number one problem is that absolutely everything the commission does, from beginning to end, is subject to immediate public release and observation,” he wrote. “No other agency, executive, legislative or judicial, conducts its work in that manner.”

The Willingham case has been in play since 2008, when the commission agreed to hear a complaint brought by advocates for the wrongfully convicted alleging that the arson investigation used to convict him was effectively “junk science.” Last summer, the case gained notoriety when a 16,000-word New Yorker article detailed the findings of Craig Beyler, a fire science expert the commission hired to evaluate the state’s evidence. Beyler’s report concluded that the investigators were “wholly without any realistic understanding of fires and how fire injuries are created.”

Two days before the commission was scheduled to take up the Willingham case last October, Perry abruptly replaced its chairman, Sam Bassett, an Austin criminal defense attorney, along with two other commissioners. When Bradley took Bassett’s spot, he indefinitely postponed the board’s consideration of the case and shifted the commission’s schedule from meeting every two months to every three. Perry’s action kept the board from reaching a potentially damaging conclusion in the case during a competitive primary campaign.

In a general election campaign that is itself competitive, the resolution of the case likewise could have been an issue. If commissioners had approved Bradley’s report at Friday's meeting, the investigation would have been wrapped up with no explosive findings before Election Day. Now it will likely drag on into the next legislative session — giving lawmakers even more opportunity to air their concerns.

Revealing the truth

Willingham made it back on the agenda at an April meeting, but members only addressed it briefly to task a subcommittee, whose deliberations would be private under the Open Meetings Act, with reviewing the case. On Friday, Kerrigan, who has refused to speak to the media, revealed that the subcommittee had not met since July.

At the full commission’s July meeting, Bradley questioned the basis of Beyler's report, saying it did not properly detail the professional guidelines Texas fire investigators used at the time and focused on publications and research rather than manuals or materials the investigators would have used. It's not fair "to go back in time” and apply scientific standards that weren’t used, said Bradley, adding that investigators were doing what they were “taught at the time." At his prompting, the commission agreed to solicit the opinions of two additional fire experts, whose conclusion — that “there was no uniform ‘standard of practice’” for investigators “in Texas or elsewhere” at the time of the Willingham trial — was the basis for Bradley clearing Willingham’s arson investigators of negligence in the draft report.

In July, commissioners also debated a memo that Bradley sent them arguing their jurisdiction was limited to laboratories accredited by the Department of Public Safety. That would have precluded them from considering Willingham's complaint, which hinges on the allegedly faulty investigations and testimony of experts at trial, not analysis conducted in a laboratory. After sharp criticism from lawmakers and others prior to the July meeting, Bradley said his memo was intended only as a reference point for members and not to halt their review mid-stream — though, "certainly some of the issues that were raised in the memo could question whether the commission has jurisdiction over the Willingham case."

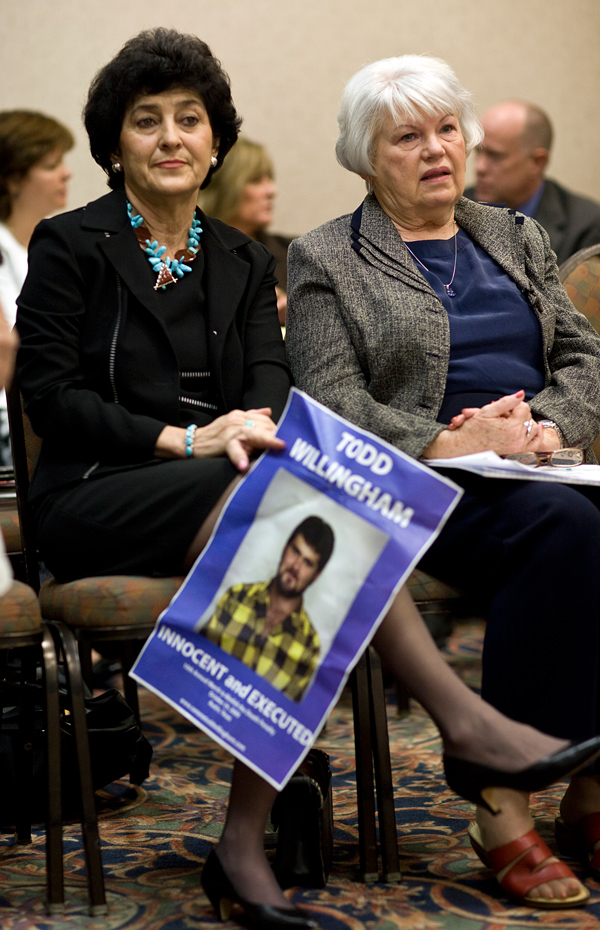

Judy Willingham Cavner, left, sits with Eugenia Willingham at Friday's meeting.

Willingham's stepmother, Eugenia, and two of his cousins, Patricia Willingham Cox and Judy Willingham Cavner, attended Friday’s meeting. During a lunch break, Eugenia Willingham told reporters she was encouraged that other commission members were "standing up" to Bradley. Cox said she believes her cousin was wrongfully executed and that Perry is to blame. "The governor was made aware of it. He knew those standards were wrong in 2004," she said.

The commission will take up the Willingham case once again on Nov. 19. On Friday, Kerrigan estimated that it would likely take another meeting after that for the commission to reach a conclusion.

When asked how he thought the commission should proceed on the case now that it won’t meet again until November, Bradley e-mailed: “You should direct that question to the commissioners who, despite having hundreds of pages of information and a multitude of expert opinions available for two years, continue to think that hearing from yet more people might reveal the truth.”

He added, “I seriously doubt the next hearing will be anything more than a political farce.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Morgan.jpg)