Jailhouse Revival

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/20100810-DSC_0944.jpg)

It was nearly seven years and $138 million in the making. Dozens of uniformed officers and county officials erupted in jubilant applause Wednesday when the state’s top jail official announced that for the first time since 2004, the Dallas County lockup — the seventh-largest in the nation — meets state jail standards.

“Dallas County is in compliance,” says Adan Muñoz, executive director of the Texas Commission on Jail Standards. “In my lifetime.”

The news came after two long, tense days in which inspectors from the commission — trailed by a nervous, hovering entourage of county officials — filled cell after cell with smoke in the Sterrett Tower just outside of downtown Dallas. The smoke evacuation system has been the stickiest of dozens of problems that have plagued Dallas County jails since 2004. Eight times from 2004 to 2010, inspectors from the commission assessed the facilities and issued failing grades. The facility racked up violations ranging from poor inmate health care to backed-up plumbing and insufficient staff training. And each time the infernal smoke removal system that inspectors tested from early afternoon Tuesday until late at night and all day on Wednesday has bedeviled local officials, failing time and again. And on top of it all, the jail is under federal court order to improve mental and medical health care following a 2006 Department of Justice investigation, according to The Dallas Morning News.

“This is so major,” says Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price, tall, broad, bespectacled and bow-tied, flashing the same pearly white smile that was pasted on his SUV in the jail parking lot.

The day before, Price had spent hours on end in the jail as sirens squawked, strobe lights flashed and thick smoke filled cells. As an acrid plume enveloped one cell, he looked on anxiously, along with a small horde of jail officials and County Sheriff Lupe Valdez. Inspector Brandon Wood calmly eyed the timer on his iPhone, watching the cloud slowly dissipate and checking to see that all the alarms were triggered in plenty of time to get inmates and guards out of harm’s way in case of a real fire. When the air cleared, the sirens quieted and the strobes stopped, the anxiety on the faces of Wiley and the other officials turned — if only briefly — to relief. Then the process started all over again in another cell.

Valdez has been in charge of the jail since 2005, when she took over the sheriff's post from Jim Bowles. A former federal agent, she has since borne the brunt of the public's disappointment with the facility’s repeated failures. “Everybody criticizes us because it’s taken so long,” says Valdez, an unimposing woman with short, dark, bobbed hair, an easy smile and small round glasses perched on her nose. If not for the black uniform and the holster around her waist, she’d be easily mistaken for someone’s abuelita.

It’s taken so long to fix the jail for many reasons, Valdez says, most notably what she describes as the deplorable conditions she found there when she was first elected. Human excrement was spread like paint on walls in the mental health unit, she says. About 800 inmates were forced to sleep on the floor, and the walls were caked with 20 years of filth and cigarette smoke. Inmates “were kept here; they were not taken care of,” she says.

Commissioner Price, who has served for more than 25 years on the county court that oversees the jail, says Valdez inherited “the jail from hell.” Bowles, the former sheriff, allowed the facilities to deteriorate over the years, he says; Price intimates that the longtime lawman had some sort of good-ol'-boy arrangement with state inspectors who probably overlooked violations. “All those many years, we probably were not in compliance,” he says. But because there were no inspection problems, Price says, he and other commissioners had no reason to worry about the jail conditions. “This is 19 years of benign neglect,” he says. Suddenly, when Bowles left the jail and Valdez took over, things changed, and in a matter of a few short years, the facility went from being a model of safety to a den of the discarded and disgusting. “I just find that peculiar at best,” Price says.

That’s plain poppycock, Bowles says. For 19 consecutive years, the jail passed state inspections with flying colors, he maintains, and there were no special deals with state inspectors. The county rightly bragged about its stellar compliance record. “I had a model jail,” Bowles says. Then, in 2004 — just as he lost his bid for re-election in the GOP primary amid scandals over jail commissary contracts and campaign funds — the state jail inspectors made their annual surprise visit. Inspector Mark Wilson documented at least eight areas of non-compliance. He found more than 100 inmates crammed into a holding cell designed for 43. Intercom systems didn’t work. The smoke removal system didn’t work. Inmates went without proper health screens, and the jail had too few jailers. Dallas County Jail received its first notice of non-compliance — the first of many.

Bowles has his own theory about what went wrong in the jail as he prepared to leave the sheriff’s office after two decades. He says political opponents in his own party sabotaged the facility so that it would fail the inspection. As he tells it, their goal was to embarrass Bowles so badly that he would lose the election. They would win, take over, quickly fix the problems and be lauded as public heroes in Dallas County. But Bowles says his Republican foes’ plans backfired when Democrat Valdez won the general election instead. The trouble was, he says, she simply didn’t know how to fix all the problems — and that’s why the jail has failed again and again to pass muster with inspectors. “We managed the jail the way a jail was supposed to be handled,” Bowles says.

Whether it was political chicanery, benign neglect or official corruption that led to the deterioration, the repeated jail failures became a public blemish for the county.

In 2005, inspectors cited the facility for 11 areas of non-compliance, including many of the same issues that appeared in the 2004 report. Cells were still overcrowded, intercoms still didn’t work and the smoke removal system remained out of commission. There were rusty showers, clogged drains and broken toilets. This time, the state inspector also noted that it took an average of six days for medical staff to respond to an inmate sick call — even though state standards require a response within 72 hours.

The smoke system remained inadequate in 2006 when inspectors visited. Inmates still occupied overcrowded cells. Medical staff wasn’t responding quickly enough to sick calls. Sanitation and maintenance problems persisted. That year, the jail got two failing report cards. Inspectors made a second visit after an inmate escaped. They discovered that the escapee had gone unobserved for five hours before he absconded.

The next year, there were even more violations — 14 — including the old ones plus some new ones, like failing to give inmates clean clothes, sheets and towels. In 2008 and 2009, inspectors still found at least nine standard violations. And two separate additional inspections of the smoke removal system in 2009 were failures. After failing again that year, the jail commission forced the county to take out more than 900 jail beds.

The continued failures came despite ongoing efforts to bring the jail back into compliance. When Valdez took over as sheriff, county officials from law enforcement and the county commissioners’ court to the district attorney’s office and public hospital began meeting to develop solutions. Every Monday for the last 49 months — except for holidays — the team has met to discuss plans to meet state standards, Price says. The county spent more than $138 million to improve the facilities. Nearly half of that — about $66 million — was spent on construction of a new jail tower with 2,300 beds. The county spent nearly $1 million just on replacing old showers in the cells. And millions have been spent to pay jailers overtime to ensure that the facility meets the state requirement of one jailer on duty for every 48 inmates. The transformation is “miraculous,” Price says.

Inmate advocates say the jail isn’t perfect, but they agree the change has been remarkable. “I think, overall, the women that we encounter have not had as many complaints as they used to,” says Bette Buschow, executive director of Resolana, a Dallas-based nonprofit organization that provides education and counseling to female inmates. Most of the women are housed in the county’s new Kays Tower, and the sheriff’s office provides classroom space for Resolana to give lessons in art, meditation, parenting and other life skills. And the area where inmates with mental health problems stay has vastly improved, Buschow says. No longer does the smell of feces waft down the hall. “In terms of the physical facility, it’s a leap ahead,” she says.

Up in smoke

Through the transformation, though, the biggest thorn in Dallas County’s side has been the smoke removal system in Sterrett Tower. The biggest fire danger in a jail is not the flame itself but the smoke that can injure and kill inmates and guards. The 8,000-square-foot maze of jail cells was built in 1991 with a smoke removal system very different from the one state standards now require. The entire facility had to be retrofitted with smoke removal equipment at a cost of more than $20 million.

In 2009, as the frustrations with the failing smoke removal equipment and other systems continued, the county hired former Jefferson County Sheriff Carl Griffith to help. Griffith, now a consultant to businesses and government agencies, spent the last 15 months testing and retesting, fixing and tinkering with the smoke removal system to get it right and advising county officials about how to finally meet the jail standards. “I’ve seen incredibly hard work, team work … to fix this problem,” Griffith says.

Finally, in March 2010, when state inspectors made their surprise visit to the Dallas County Jail, the list of violations had dwindled to just four items. Jail commission director Muñoz commended local officials for vast improvements, but he still couldn’t issue a certificate of compliance. They had to get that smoke system remedied.

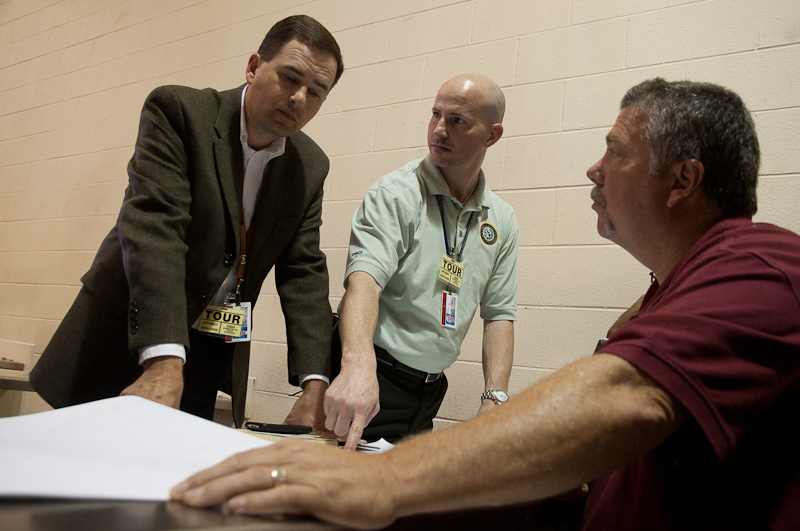

Griffith sat Tuesday at a stainless steel table inside a beige cell block, his freckled hands folded near his chin, and intently observed the smoke billowing up into a closed cell. His eyes followed inspector Brandon Wood as he methodically checked each of the other cells in the block to see whether smoke was seeping from one to the other. Griffith peered at the timer on Wood’s iPhone. To meet state standards, the system would have to detect the smoke in less than 60 seconds, setting off the sirens and strobe lights, and it would have to clear the smoke from the cell within 15 minutes. As the timer clicked past nine minutes, only a faint haze of smoke remained in the cell. Griffith smiled and looked at Wood, who stoically jotted notes in a bound journal. “You like it?” Griffith asked, barely concealing his enthusiasm. There was no response from Wood. The timer ran out, and Wood’s cowboy boots clomped along the cement floor as he moved on to test another area. There would be dozens more smoke tests over the next two days as Griffith, Price, Valdez and the entourage of jail officials hovered in anticipation. And the second day would not go as smoothly as the first.

On Wednesday at about 5 p.m., a weary but smiling group of jail officials and county leaders, including Valdez and Price, gathered for a press conference at the Frank Crowley Courts Building. The announcement had been set for 11 a.m. but was pushed back for hours as inspectors and jail staff continued tests and fixed glitches to make sure the smoke system was ready for final approval. Muñoz, stationed in the center of the knot of local officials, announced the news: “We’re satisfied that Dallas County is in complete compliance as of today.” Still, Muñoz warned that the jail could continue to struggle with issues of overcrowding, which the commission plans to monitor closely.

Valdez says she understands the public frustration over the years of troubles and millions of dollars it took to get the jail back in the state’s good graces, but she says it was more important to get the job done right than to get it done quickly. “It’s working,” she says. “We are becoming a model.”

Price says he is ecstatic that after years of work and millions of dollars the county has finally “delivered the baby.” Maintaining acceptable conditions in a facility that houses about 7,000 inmates — about 15 percent of them with mental illness — on any given day, will continue to be a challenge, he says. “Now, we’ve got to raise the baby.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/grissom-brandi.jpg)