The Charter School Waiting Game

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/110909_charterschoolwait_jv.png)

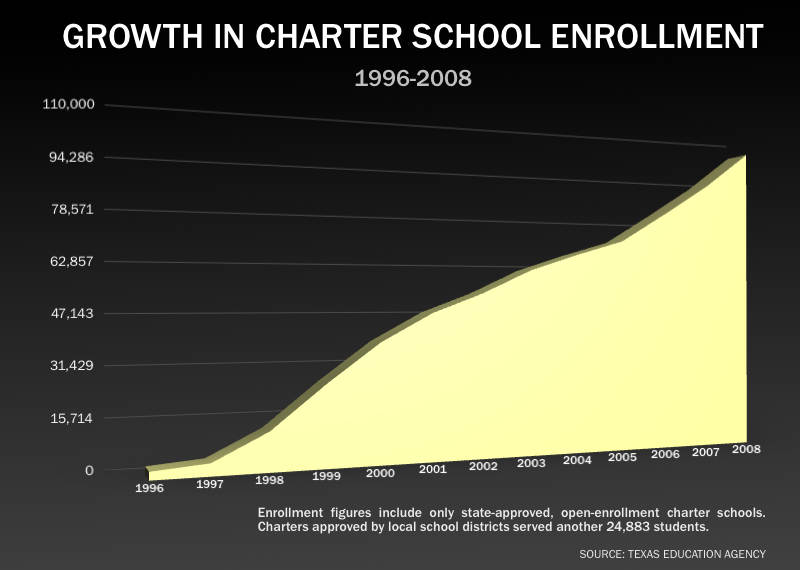

More than 40,000 families signed up on charter school waiting lists across the state last year, the bulk in big cities with ailing public school systems. Such demand, advocates say, argues for expanding charter schools, which currently serve just two percent of state students.

The waiting list total, for the 2008-09 school year, was amassed by the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation, which published a similar study a year ago that put the prior-year number at nearly 17,000. The waiting lists grew even as the state added charter schools, boosting enrollment from nearly 114,000 to 128,000.

The demand was concentrated almost entirely in Houston, Dallas, the Rio Grande Valley and Austin and their surrounding regions, which include high-poverty areas — more likely to have both an entrenched charter school community and failing traditional public schools that parents might seek to escape. Only about 3,000 families signed up on waiting lists outside those areas.

“You see large waiting lists in areas … where charters have strong market share,” said study author Brooke Terry. “We believe that’s because word of mouth among parents has driven demand. It also has something to do with success. In all these areas, there are large, established charter networks.”

Houston, for instance, is a national Mecca for the charter school movement and the home of the Knowledge is Power Program, a national charter network praised by many for posting high performance with relatively high-poverty enrollments. The Yes Prep charter network, another highly regarded operator, also run schools in Houston.

In the Houston/Galveston region, nearly 29,000 students attend charters — and nearly 18,000 more are on waiting lists to join them, according to the foundation study.

At an afternoon news conference at Harmony School of Excellence-Austin, parents and former teacher Lupe Arenivar said her son had been turned away from one Harmony charter school, relegated to the waiting list, before finally getting accepted this year. She moved recently from El Paso to Austin, she said. She wasn't impressed with her traditional public school options, and couldn't afford private schools, she said.

This year, her son, David, has blossomed in the new setting, which emphasizes his interests in science and math.

"He has a lot of homework — and it's hard. In his other school, it was easy and he finished in just a few minutes," she said. "There's another little boy on the waiting list, he lives two doors down from us. He comes over all the time, and when he sees the projects David is doing, he says, 'I wish I was doing that. I wish I was learning that.'"

Though waiting lists are hardly an exact measure of market demand, foundation researchers believe they are as likely to underestimate the demand as to inflate it. It’s likely that many parents signed up on lists for more than one school, and that schools might not purge parents from lists who no longer want to attend the school.

However, it’s also likely that many parents didn’t bother to put their names on waiting lists at high-demand campuses, figuring they had little chance of admission. Further, the foundation counted only the lists at charter schools responding to its survey — only about half statewide, in both years. That could contribute to undercounting, although Terry acknowledged that many schools that didn’t respond probably didn’t have waiting lists.

Charters are public schools freed from most state and regulations. They operate independently or in clusters, controlled by private entities, most often nonprofits, who contract with the state or the local school system. In Texas, charters schools in generally serve a slightly higher proportion of poor and minority students than traditional public schools, and about a third of charters specialize in “drop out recovery.”

The waiting list data should not necessarily be interpreted as a measure of charter school quality, and in fact may be more of a comment on the lack of quality in nearby traditional public schools, said Linda Bridges, president of the Texas chapter of the American Federation of Teachers, a teachers union which has fought charter expansion. All the same, the charter movement has had its own bad apples and the state has yet done a poor job of overhauling or closing low performers, Bridges said.

“When you look at charter vs. public, and charter expansion, you need to be looking at the quality of them before you look at more quantity,” she said. “I acknowledge there are (traditional) public schools with lots of problems. But does that (waiting list) necessarily mean that the charter around the corner is high-quality?”

Moreover, Bridges said, other research suggests charter school student attrition — students leaving after admission — is higher than at regular public schools, in part because charters have more freedom to expel students or counsel them out.

The foundation, along with the Texas Charter School Association, used the study as an occasion to argue again for lifting the state’s cap on charter holders at 215, a measure which failed in the last legislative session. The cap, however, has already been shot through with loopholes and won’t prevent charter expansion any time soon. The state recently announced it would allow higher-performing charter operators to expand without even asking the Texas Education Agency.

At the news conference, Sen. Dan Patrick, R-Houston, nonetheless pledged to keep pushing to raise or abolish the current state cap on the number of charters, currently set at 215. His attempt to do so last session, in SB 1830, was killed by procedural objections in the final hours of the session, he said, despite having been approved 31-0 in the state Senate. It never came up for a vote in the House.

"We had the votes in the House," he said. "But one or two members who don't like charters killed it."

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/tt_bio_thevenot_brian.jpg)