The Hidden Food Line

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/120509_foodstamps.jpg)

In July, Eunice Sierra, a cancer survivor, started trying to get food stamps renewed for her daughter, a 20-year-old single mother with schizophrenia.

Repeatedly, they trudged down to the state Health and Human Services offices at 404 Brady Boulevard in San Antonio. Nearly every day for two months, they joined the early morning line of 100 or so people, many desperate. Each time, they left empty-handed. The most common answer: Their caseworker had “left for the day” by the time their turn came, she said.

The degrading experience drove Sierra to volunteer for The Advocates Social Services in San Antonio, where she helps others battle the bureaucracy for benefits. As she relayed the story, rage and sadness poured from her.

“I’m sorry I’m crying. It just makes me so angry, because these people’s kids are the ones who suffer. And the adults sometimes go without eating for days so they can feed their kids first,” she said. “I don’t know what these state representatives think, that these people are supposed to survive on bread and water. Or air.”

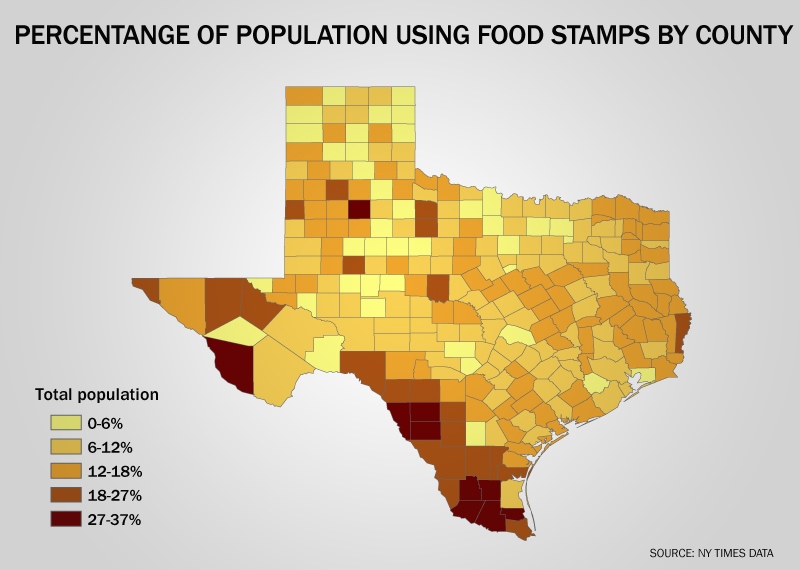

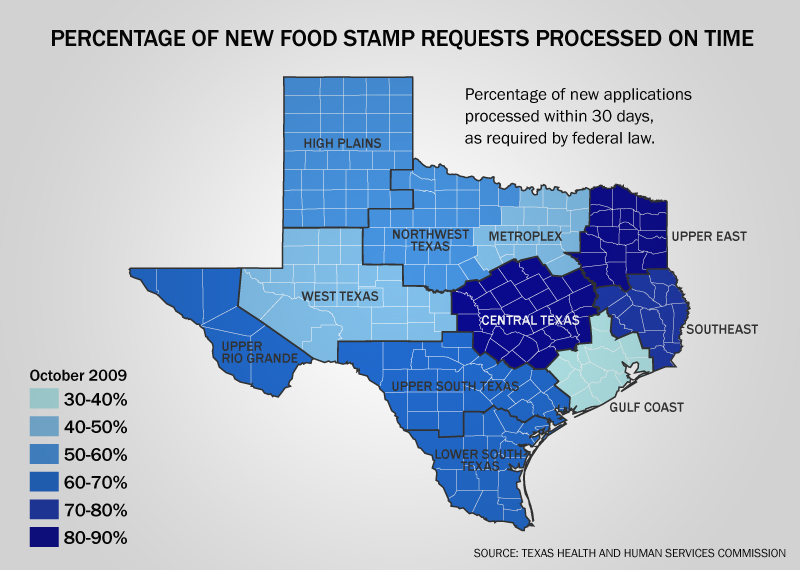

Such tales have played out across Texas over the last year, as pending food-stamp applications have soared, from about 38,000 a year ago to more than 65,000 in October. Two-thirds of those people had waited longer than the federally mandated 30 days and nearly half had waited more than 60 days. The worst delays, the agency concedes, have stranded families without help for months on end. And those figures tend to undercount the total case load because they don't capture many applications until a worker starts processing them.

Though the agency has recently made a host of changes, sparked by a lawsuit and federal compliance demands, it will struggle for months to come to unravel the bureaucratic tangles stalling the applications of the state’s neediest citizens. Since September, under the watchful eye of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the agency has added about 500 employees — net, including attrition — and reassigned about 100 veteran employees to teams tackling the oldest cases. A report released Friday by the agency showed the first decrease in pending cases, to about 62,000 in November, a drop of about 3,000.

“They’re going to be in a hole for a long time,” said Bruce Bower of Texas Legal Services, which filed the lawsuit seeking to force the state to speed food aid to the poor. “The hole was dug over a period of six years.”

Stacks on desks

Food stamps, now called the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, would seem among the simplest benefits for the state to get right: Texas pays nothing for the benefits and only half of administrative costs. All the state must do is pass out the money so poor people, most often mothers and their children, can eat.

“I liken it to freeze-dried soup — just add water,” Bower said. “All the state had to do was add personnel. Instead, they starved the program.”

Bower's lawsuit ultimately was dismissed on technical grounds and is now on appeal, but it succeeded in bringing attention to the issue; at about the same time, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (which runs the federal program) demanded a corrective action plan from the Texas Health and Human Services Commission. The recession clearly overwhelmed state offices, especially in major cities such as Dallas and Houston. Last year’s Hurricane Ike, which left thousands on the Gulf Coast homeless, didn’t help either. But neither crisis created the commission’s troubles — they merely revealed systemic mismanagement stemming from chronic turnover, short-staffing and complications stemming from an ongoing transition away from 1970s-era computer system.

The trouble really started in 2005, with a disastrous privatization effort in which the state hired Accenture to take over enrollment under a $900 million contract that was canceled two years later after a host of foul-ups. Meanwhile, HHSC employees left in droves, believing they would soon be laid-off in the outsourcing. The departures left the agency crippled. By the time Accenture was canned in 2007, the damage had been done.

Over the last year, as demand for food stamps has spiked nationally, the ability of Texas to meet the demand plummeted.

“In Texas, we do our best to serve as few people as possible in these kinds of programs, and the underfunding of our eligibility system is now really coming back to haunt us,” said Celia Hagert, senior policy analyst for the Center for Public Policy Priorities. “That’s what makes the Texas picture different from the national picture: The reason the problems are so severe really has very little to do with the current economic crisis.”

A separate set of data measuring timeliness — the percentage of applications completed within 30 days — indicates only 57.5 percent of new applications and 71.6 percent of renewals are processed on time, according to the latest data for November.

Sometimes, the paperwork can sit for weeks or even months, said HHSC spokeswoman Stephanie Goodman.

“It’s in a stack on a desk,” she said.

14-month wait

The small improvements made so far provide little comfort to the tens of thousands of Texans still awaiting food aid. And it’s clear the agency, beyond merely hiring, must work through daunting administrative logistics and employee training and morale.

The agency’s “negative error rate” — denied benefits to people who deserve them — reached as high as one in five cases statewide in the last year, and double that in specific offices, according to the latest report on the agency’s progress to state legislators.

And the error rates may not even include the many anecdotal cases of “lost” applications.

In San Antonio, Patricia Lauren Moore, 20, filed for food stamps just before the birth of her son, Jonah. She had been attending the private St. Mary’s College, but her wealthy father shunned her because of the pregnancy, cutting her off financially.

At the food stamp office, workers told her they’d send her paperwork to fill out in two months. When two months passed, she was told she’d have to file again because her caseworker had quit and no one could find her file.

Then another four months passed — before she was told she’d have to apply yet again, because her case had “closed.” Still, nothing happened. She begged The Advocates for help recently, and after more wrangling, finally got her food stamps last week.

“Now things are falling into place. I thank God every day,” she said. “I don’t know what I would do without state programs. I won’t be on them forever. I’ll be able to provide for my son when I graduate” from a local community college.

Jonah is 14 months old now. His mother’s food stamp application was slightly older when it finally got approved.

“Defeat and desperation”

HHSC'S staffing and turnover problems are magnified by mind-numbingly arcane federal eligibility requirements, which are generally meant to prevent fraud — but in practice have prevented many deserving applicants from receiving badly needed aid.

It’s no wonder the state agency has had trouble hiring and retaining employees. First, they average only about $30,000 a year in salary. Second, it takes at least a month or two to train a caseworker — before they ever pick up their first case, Goodman said. It takes at least a year, some say two, before they become proficient enough to handle the expected caseload of eight per day.

Why does it take so long to get up to speed in an entry-level government gig?

“Good question. I wish I knew,” Goodman said. “There are so many federal regulations around this program, and no family looks the same. You might have a woman with children from different fathers, and you have to look at income and assets for each one. Then, say a grandmother lives in the house, you may have to count her income. Then you have to look at vehicles … ”

And on and on.

Combine the inherent frustration of the job with the mounting stress of both beneficiaries and employees, and it produces an agency with inexperienced and overworked staff whose morale has sunk to new depths.

Commissioner Tom Suehs took the helm of the agency in September. When he reached out to employees for suggestions last month, he got a torrent of emails in return, with workers pouring out their frustration over impossible workloads, lack of training and relentless mandatory overtime. It was a rare move for any agency head — openly inviting on-the-record employee complaints — and provided a rare window into dysfunction and flagging morale on the front lines.

“There is a real feeling of defeat and desperation,” one female employee wrote. “I am married and I have a five-year-old daughter. I spend several mornings a week crying on my drive to work because I have just left her at school at 7:45 and I know that I will not get to see her again … until she has already been put to bed.”

The upside: Suehs got a second flood of email, this time appreciative, when he responded to employees promising to ease mandatory overtime, give them a “merit” bonus and hire aggressively.

One employee wrote that Suehs had “made my day.” But then she relayed how her 15-year-old daughter had moved to live with her father because the mother worked too much. She had justified the long hours to her daughter by saying the agency’s clients needed her. The daughter reminded the single mother of her own struggles to pay bills, keep food in the pantry, fix the car window plastered with clear tape.

“At least most of those kids had their mothers home with them,” the girl said. “Why don’t you just quit your job and get food stamps?”

High and mighty

Working as a manager at The Advocates in San Antonio, Jason Mata has heard all the stories about stressed out food stamp workers. He sympathizes — to a point.

“They keep telling us, 'We’re under stress.' I understand they are working 12 to 14 hours a day, but they are drawing a paycheck from all of this,” he says. “The families who need food are the ones who are stressed.”

While Eunice Sierra’s daughter, 20-year-old Sasha Sierra, waited on food stamps, life at home became a perpetual search for the next meal. The daughter bounced between her mother’s and grandmother’s houses for meals. Her mental condition, along with an attempted sexual assault by a relative, left her “scared of everything and everyone” and unable to work, Eunice Sierra said.

Eunice couldn't work, either. Her battle with bone cancer caused another debilitating complication that required removing part of her spine. She often paid for her daughter and granddaughter’s meals out of her own food stamp allotment — until that ran out, too.

Between them, the women spent nearly six months seeking renewals of two new food stamp cards that a well-functioning office might have completed in a few days.

The rudeness of many workers and security guards at the food-stamp office — even while they failed to deliver benefits — still sticks with Eunice Sierra.

“Those people behind the glass are so high and mighty,” she said. “Well, one day they might need help, too.”

Matt Stiles did the data research and mapping for this story.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/tt_bio_thevenot_brian.jpg)