Debtors' Treadmill: Treasure Map

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/120109_CSOTravis_jv_.png)

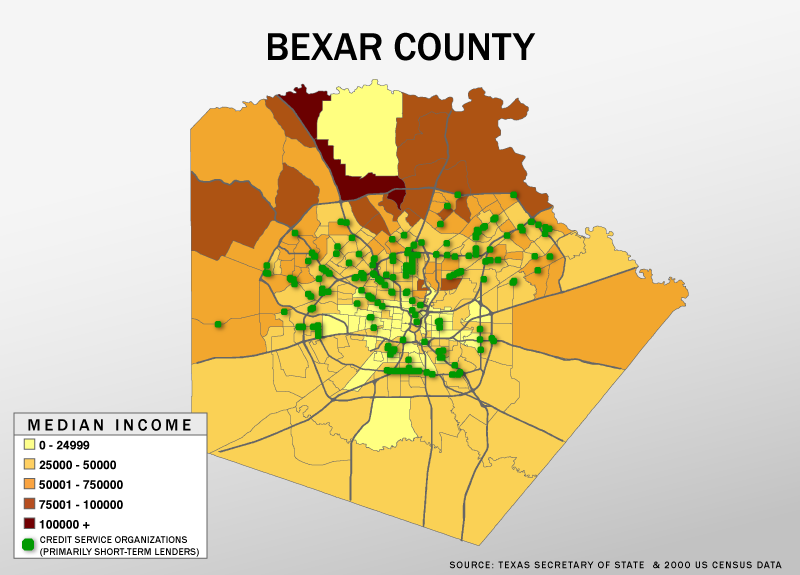

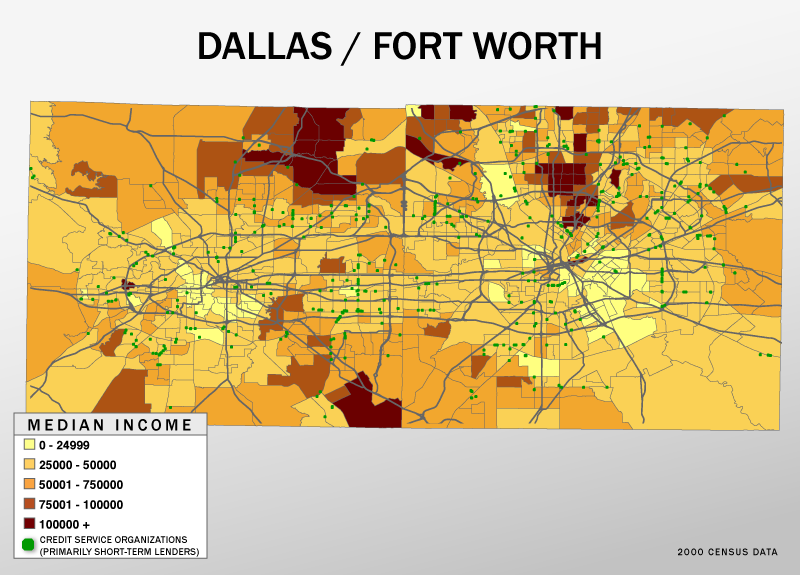

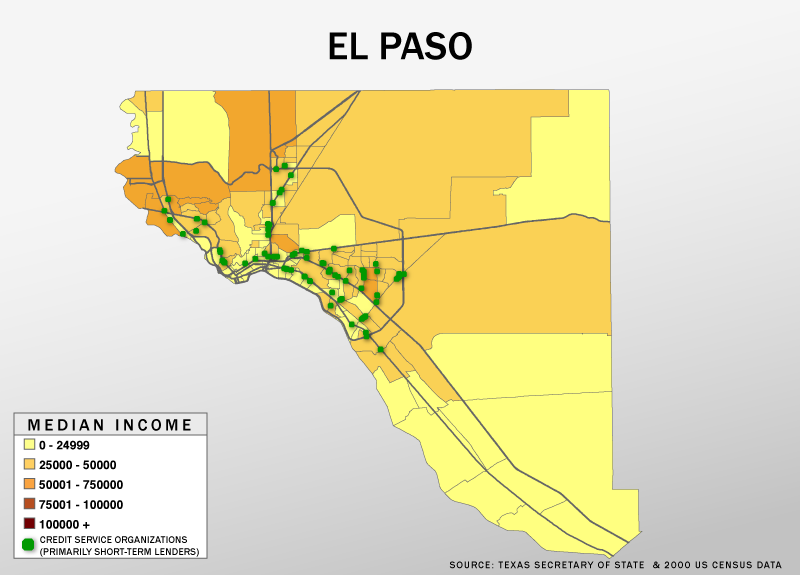

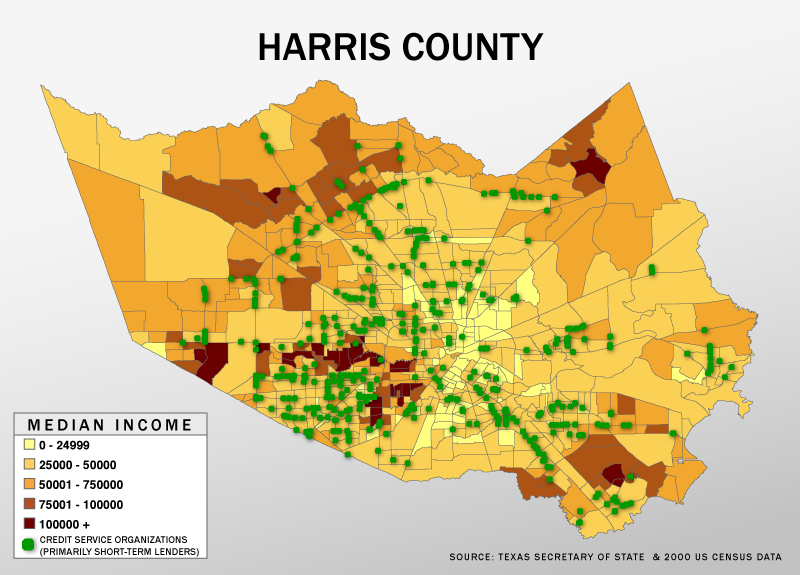

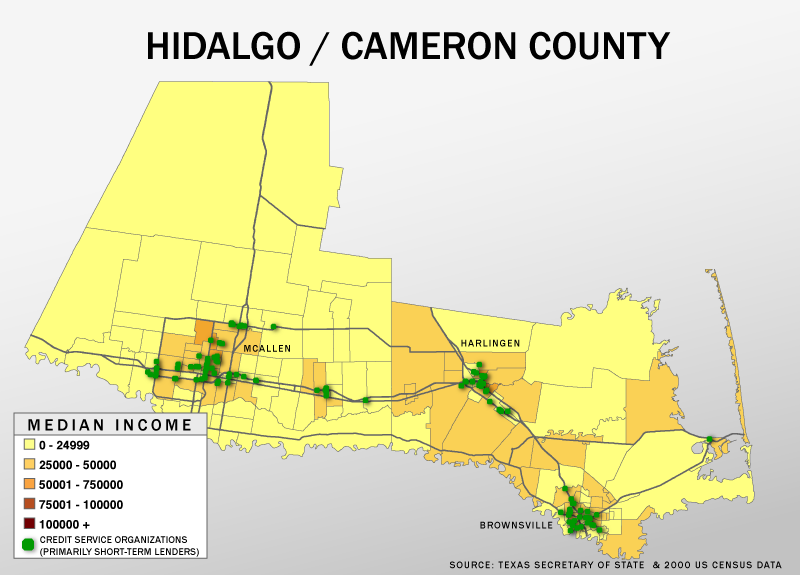

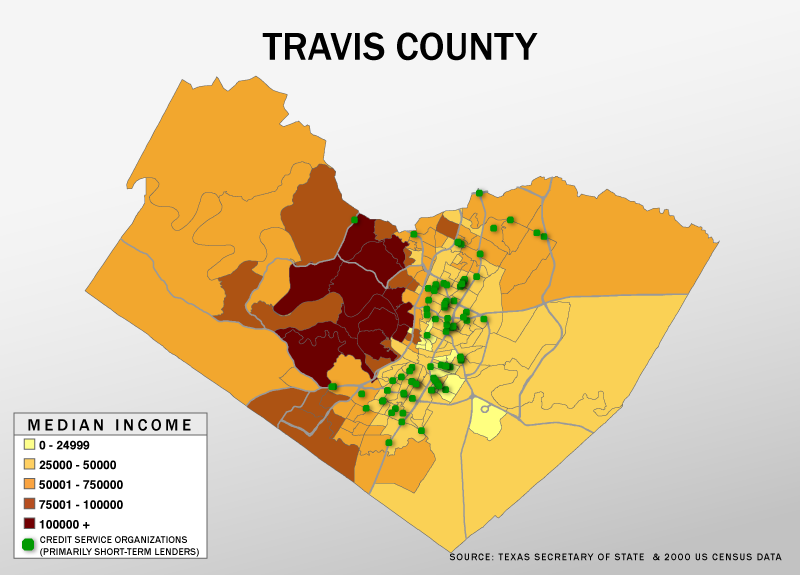

Companies that offer short-term, high-interest loans go where the business is: primarily low- and middle-income neighborhoods.

So-called credit service organizations, a group of lenders largely composed of payday and auto-title loan companies, are clustered in Texas neighborhoods that are home to families with incomes of less than $50,000 a year. We compared the addresses of lenders statewide, obtained from the Secretary of State, to U.S. Census data on median household income.

“They’re preying on folks that live paycheck to paycheck but also taking advantage of people that don’t have savings,” said Don Baylor, senior policy analyst at the Center for Public Policy Priorities, an Austin-based organization that advocates for low- and middle-income Texans.

The companies, though, argue they provide a much-needed service to those who have no credit and can’t find quick capital elsewhere.

“The research has shown small-loan customers are middle-income, educated working families,” said Rob Norcross, a spokesman for the Consumer Service Alliance of Texas, a trade group that represents credit service organizations. “You have to have a bank account and you have to have a job to be able to get one of these loans.”

Since 2005 in Texas, short-term lenders offering consumers quick loans with huge costs have gone mostly unregulated by the state. They pay $100 a year to register as credit service organizations with the Secretary of State, and can thereby charge customers enormous “fees” to use third-party lenders while avoiding Texas usury laws.

The lenders make millions from charges that rack up as consumers who are unable to pay off the debts continually renew their loans and incur more fees.

Some lawmakers, including Democratic Senators Wendy Davis of Fort Worth and Eliot Shapleigh of El Paso, have proposed measures that would regulate the industry. But those efforts stalled when met by powerful legislators and state officials who have received thousands in contributions from industry groups and their lobbyists.

When data from the state and federal governments are mapped in some of the state's largest counties, the targets become evident: More than three-quarters of those companies were located in neighborhoods where the median household income was less than $50,000, according to the 2000 Census. Only a handful of stores were located in areas where the median income was $100,000 or more.

Baylor said it’s long been the case that more payday loan stores were in areas where families make less money. But, he also said that payday lenders in recent years have been migrating into neighborhoods with more middle-income families. Many are also cropping up near university campuses.

“They are either $50 or $100 always behind or just right on the edge, so this is the population that is attempting to juggle a lot of different bills coming due, and they don’t have savings,” Baylor said.

Texas Appleseed, an advocacy group for low-income Texans, conducted a survey of payday loan users in 2008. The group’s report showed that loan users most often took out loans to cover recurring expenses, like utility bills, groceries and rent.

More than 30 percent of the loan users Appleseed surveyed made less than $10,000 per year. Nearly two-thirds of those who reported using payday loans, 58 percent, said they had to extend the loans at least once before paying them off, incurring more fees and more interest.

“There are people that literally, on payday, go from lender to lender to keep them going,” Baylor said.

But Norcross of the Consumer Service Alliance strenuously disagreed with the notion that the lenders target poor and middle-income Texans.

The stores, he said, are located in both urban and rural areas in every legislative district across the state. They are in high-traffic areas near consumers who can’t get loans from traditional banks or credit unions, Norcross said.

Our analysis also shows that many of the stores are located on or near major highways.

“They want convenient locations in areas where people shop, and where they commute back and forth to work, the same as any other retail establishment,” Norcross said.

Consumers who use payday loans, he said, make informed decisions. Fifty-eight percent have attended college, and 20 percent have bachelor’s degrees. They choose, he said, between paying bills late, using credit cards, asking friends or family for help and using short-term, high-interest loans.

“Our customers ... make reasonable choices given the alternatives they have.”

These maps show the locations of credit service organizations in select counties. U.S. Census tracts are shaded depending on median household income.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/grissom-brandi.jpg)

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/TxTrib-Staff_0016_StilesMatt800.jpg)