Amid Scramble for Water, a Push for Desalination

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/LastDrop-3.jpg)

SAN ANTONIO — Drilling rigs in the midst of cow pastures are hardly a novelty for Texans. But on a warm May day at a site about 30 miles south of San Antonio, a rig was not trying to reach oil or fresh water, but rather something unconventional: a salty aquifer. After a plant is built and begins operating in 2016, the site will become one of the state’s largest water desalination facilities.

“This is another step in what we’re trying to do to diversify our water supply,” said Anne Hayden, a spokeswoman for the San Antonio Water System.

More projects like San Antonio’s could lace the Texas countryside as planners look to convert water from massive saline aquifers beneath the state’s surface, as well as seawater from the Gulf of Mexico, into potable water. The continuing drought has made desalination a buzzword in water discussions around the state, amid the scramble for new water supplies to accommodate the rapid population and industry growth anticipated in Texas. But the technology remains energy-intensive and is already causing an increase in water rates in some communities.

“If you look around Texas and you look at the climate situation and the fact that the reservoirs are being drawn down, there just isn’t much of an alternative,” said Tom Pankratz, the Houston-based editor of the Water Desalination Report, who also does consulting for the industry.

Across the state, 44 desalination plants — none using seawater — have been built for public water supplies, according to the Texas Water Development Board. Ten more, including San Antonio’s, have been approved for construction by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality.

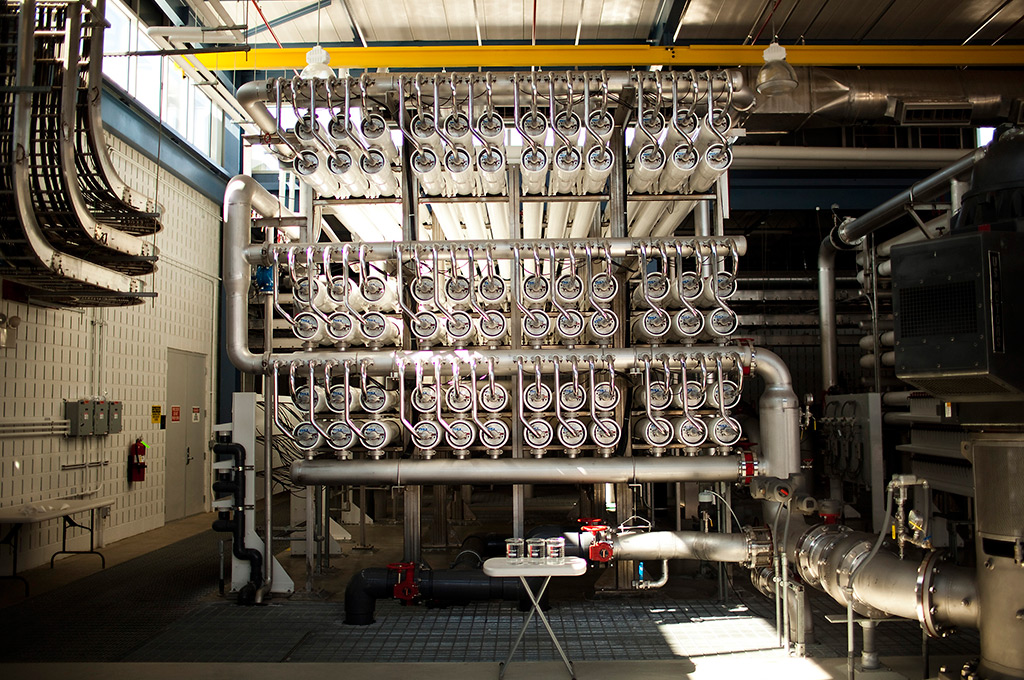

Most projects are small, capable of providing less than three million gallons per day, often for rural areas. The state’s largest is in El Paso, where the $91 million Kay Bailey Hutchison Desalination Plant, completed in 2007, can supply up to 27.5 million gallons of water a day, though it rarely operates at full capacity because of the high energy costs associated with forcing water through a membrane resembling parchment to take out the salts. (Production of desalinated water costs 2.1 times more than fresh groundwater and 70 percent more than surface water, according to El Paso Water Utilities, which said that the plant's rate impact amounted to about 4 cents for every 750 gallons of the utility's overall supply.) Last year, the plant supplied 4 percent of El Paso’s water.

Interest in desalination surged more than a decade ago, when the technology became more efficient and cost-competitive, according to Jorge Arroyo, a desalination specialist with the Texas Water Development Board. But the severe drought of the past two years has triggered extra calls to his office. Texas holds 2.7 billion acre-feet of brackish groundwater — which translates to roughly 150 times the amount of water the state uses annually — in addition to some brackish surface water. The state water plan finalized this year envisions Texas deriving 3.4 percent of its water supply from desalination in 2060. (It is less than 1 percent now.)

Environmentalists argue that desalination is not a silver bullet because it is energy-intensive and requires disposal of the concentrated salts in a way that avoids contaminating fresh water. Texas should first focus on conservation and the reuse of wastewater, said Amy Hardberger, a water specialist with the Environmental Defense Fund.

“What needs to be avoided is the, ‘Oh, we’ll just get more’ mentality,” she said.

But getting more is what many Texans want. Odessa, which draws water from dangerously low surface reservoirs, is considering a desalination plant that could ultimately become bigger than the one in El Paso. (Odessa’s deadline for proposals is next week.)

Separately, a planned power plant near Odessa is studying prices for the technology. John Ragan, the head of Texas operations for NRG Energy, envisions natural gas power plants along the coast that desalinate water overnight when they are not needed for electricity. Residents near the half-full Highland Lakes in Central Texas say that desalination could reduce the water-supply burden on the lakes. Texas Tech University aims to begin wind-powered desalination research later this year, in the West Texas town of Seminole.

The San Antonio project is estimated to cost $145 million in its initial phase, with a daily production capacity of 10 million gallons, and $225 million assuming it is built out to a daily capacity of 25 million gallons (which is possible by 2026). The cost is significantly higher than El Paso’s project, but San Antonio officials say that the figures reflect additional factors like acquiring land — and so far, the project is under budget. Local water rates, along with $59 million in low-interest loans from the Texas Water Development Board, are financing the project.

Desalination means “you’re going to have to spend some money,” said state Rep. Lyle Larson, R-San Antonio. But it is worthwhile, he added, because “our whole economic future could be up in the air.” Texans seeking a model, Larson said, should turn to Australia, where a major drought last decade spurred billions of dollars of investments in desalination.

Australia’s focus has been desalinating seawater. That is an option for the Texas coast, but desalinating seawater generally costs more than twice as much as desalinating groundwater because seawater is saltier. Energy can account for 60 to 70 percent of the day-to-day operating costs of a seawater plant, estimated Pankratz, the Water Desalination Report editor.

The largest seawater desalination plant in the country, which is slightly larger than El Paso’s brackish water plant, operates in Florida. Proposals are inching forward for a seawater plant in Texas. The Laguna Madre Water District, based in Port Isabel, completed a pilot seawater desalination project two years ago and is now looking for property on the north end of South Padre Island to locate a larger facility, said Carlos Galvan, the water district’s director of operations. Desalination would reduce the utility’s dependence on the often-diminished Rio Grande.

The Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority is also mulling seawater desalination, perhaps in the greater Victoria area. It has asked companies to submit project proposals by mid-September, and it may try to locate the water plant with a power plant, as is done in Saudi Arabia, to boost efficiency and cut costs.

Officials with both Laguna Madre and Guadalupe-Blanco hope to acquire some financing from private companies. But government at all levels, from water agencies on up, will be the key player. In El Paso, the federal government contributed $26 million in grants — more than a quarter of the cost — for the desalination plant.

The Texas Water Development Board has issued $7.1 million in grants for desalination projects since 2000, according to Arroyo, the desalination specialist.

But “we don’t have any more funds for desalination,” he said. The board asked the Legislature for $9.5 million in financing for seawater desalination last session but did not get it.

Gov. Rick Perry has advocated for desalination in the past, but he has spoken little on it recently. Expanding the technology “at a cost that is affordable to consumers will be an important part of any future water plans in the state,” Lucy Nashed, a spokeswoman for the governor, said in an email.

Officials at the Texas Desalination Association, a new advocacy group, acknowledge that requests for money will probably fall on deaf ears. But they say that the state can help by easing regulations — for example, a requirement that every desalination project include a lengthy pilot study — and by doing more extensive mapping of Texas’ brackish water resources.

“If we eliminate some of the red tape and some of the permitting issues,” said Paul Choules, the group’s president, “it reduces a lot of the upfront cost.”

This article is the second in a four-part series on water use in Texas in an age of drought. Part One is about cities raising water rates. Part Three is about the rush for reclaimed water. Coming Tuesday: Conservation efforts in the state.

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/TxTrib-Staff_0013_GalbraithKate.jpg)