Crude Concerns

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/keystonepipeline.jpg)

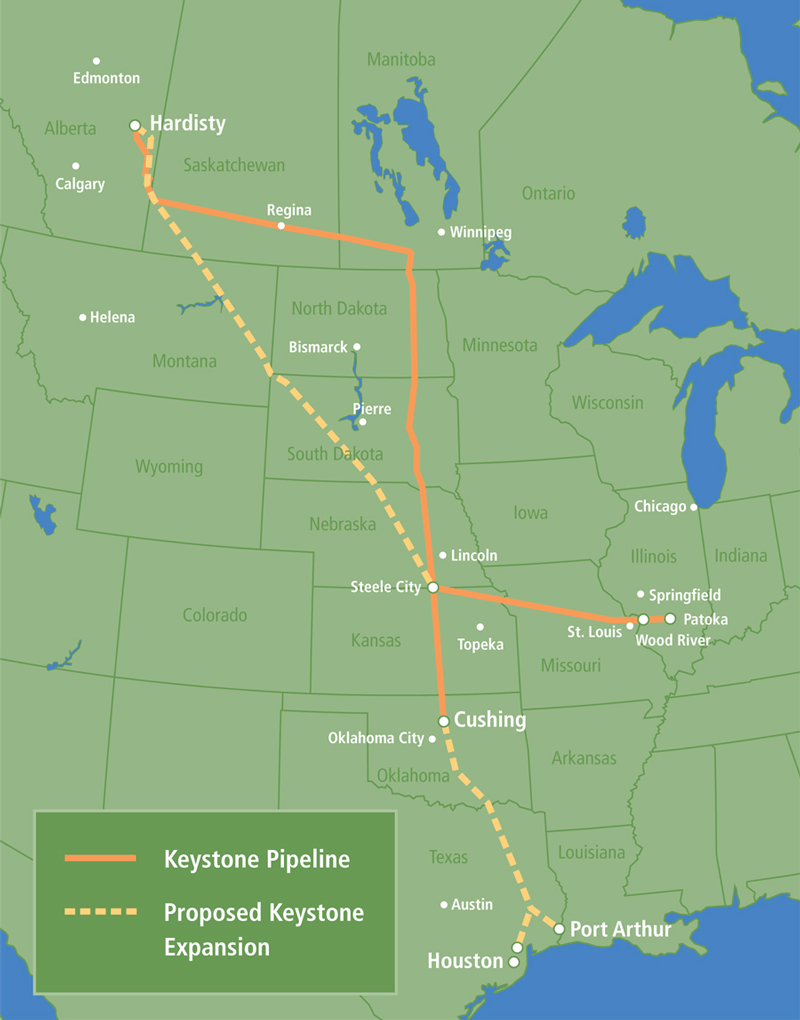

Anxiety is building about a proposed oil pipeline that would run through East Texas, ferrying Canadian crude to Port Arthur and Houston for refining.

The pipeline, called Keystone XL, would be built by TransCanada, a Canadian pipeline and energy company. It would be part of a $12 billion pipeline system whose first segment, from Alberta to Illinois, will be fully operational in a month. Construction of the Texas and Oklahoma portion is scheduled to start early next year, TransCanada says. But a number of federal, state and local permits are still needed, and the project could be set back by heightened concerns about the oil industry in the wake of the Gulf disaster.

The oil would come from Canada's tar sands, the dirtiest and most controversial source of oil extraction in North America, but one that is of fast-rising importance to the United States. Tar sands are an amalgam of clay, sand, oil and water that is typically extracted from the ground by strip mining. The process produces three times more greenhouse gases per barrel as conventional oil, according to the Pembina Institute, a Canadian environmental watchdog. It leaves behind toxic tailing ponds and destroyed forests.

Texas already has more pipelines than any other state, and some Texans favor the project because it will create jobs. "It's almost like spaghetti when you look at it, so another pipeline is not going to be any big news here," says Jim Rich, president of the Greater Beaumont Chamber of Commerce, adding, "Anything that gets product to these refineries is going to be good for local jobs and the long-term viability of our areas."

But Texas environmentalists argue that tar-sands crude, in addition to being environmentally destructive at the source, will increase greenhouse gas emissions in the Houston area, just as the federal government is paying more attention to climate change. Refining tar-sands oil "will just further increase Houston's ozone and air pollution problems," says Eva Hernandez, the field organizing manager of the Sierra Club's Texas arm.

Jim Prescott, a spokesman for the pipeline project, counters that Canadian crude is crucial if the U.S. wants a reliable oil supply from a friendly neighbor. "The alternative is we continue to import oil from less than reliable sources," he says. The U.S. already imports more oil from Canada than any other country, and Prescott says that the tar-sands oil will be used in the United States after refining (as opposed to being shipped overseas). Gulf Coast refineries have extra capacity for heavy crude, he says, due to Mexico's decreased production and Venezuela's shift to other markets.

The Texas and Oklahoma portion of the pipeline still awaits approval from the U.S. State Department, which is involved because it has the authority to issue a so-called "Presidential Permit" for cross-border pipelines. (Another segment of pipeline, through Montana, South Dakota and Nebraska, also awaits State Department approval as part of the same permit application.) A range of other permits — from the Army Corps of Engineers, from counties for road-crossings and so forth — are also still needed, according to Prescott. No other major Texas pipelines are known to be in the offing, according to the Association of Oil Pipelines, a Washington-based trade group, which says this would be the first big pipeline bringing Canadian crude to Texas.

The Texas and Oklahoma portion of the pipeline still awaits approval from the U.S. State Department, which is involved because it has the authority to issue a so-called "Presidential Permit" for cross-border pipelines. (Another segment of pipeline, through Montana, South Dakota and Nebraska, also awaits State Department approval as part of the same permit application.) A range of other permits — from the Army Corps of Engineers, from counties for road-crossings and so forth — are also still needed, according to Prescott. No other major Texas pipelines are known to be in the offing, according to the Association of Oil Pipelines, a Washington-based trade group, which says this would be the first big pipeline bringing Canadian crude to Texas.

The 36-inch Texas pipeline would go to Nederland (a terminal near Port Arthur), and TransCanada hopes to build an additional 47-mile spur to Moore Junction, in Harris County. It would have the capacity to bring 500,000 barrels per day into Texas. (By comparison, about 1.3 million barrels have been spilled collectively in the Gulf so far, using the low end of an estimate released Thursday of 25,000 barrels per day for the spill.) It would be the second major crude pipeline to reach the Gulf Coast from the Midwest, according to the State Department.

The State Department has issued a draft environmental impact statement on the project; the public comment period has been extended to July 2. Last month, the department conducted four meetings in Texas about the pipeline: in Liberty, Beaumont, Livingston and Tyler. Another meeting will be held in Houston on June 18, following a request last week from Mayor Annise Parker.

"Houston is the country's fourth-largest city and it continues to have a robust partnership with the oil and gas transportation and refining industries," Parker wrote. "However, Houston's citizens should be afforded the opportunity to inform themselves about this project and offer comments to the Department if they so choose. It seems particularly appropriate at this time to seek greater public participation in evaluating the environmental impacts of permitting decisions."

Other concerns have surfaced over the pipeline. Among them, environmentalists note that TransCanada has applied for a special permit from the U.S. Department of Transportation that would enable it to use thinner pipe than is normally allowed. The already built part of the Keystone pipeline, from Alberta to Illinois, received a permit of this type and got built with the lighter material, and natural gas pipelines are routinely allowed to be built that way without needing an exemption, Prescott says.

The steelworkers' union, which presumably wants more steel to be used, shares these concerns. Granting the permit "would increase the risks of ruptures, leaks and spills and lessen pipeline safety by the use of thinner pipe and greater operating pressure," Thomas Conway, the vice president for administration of United Steelworkers, wrote in a letter last year to transportation officials. TransCanada's transportation department permit application is still pending.

Prescott, the pipeline representative, says the concerns are misplaced: "Thickness is not the issue. The issue is strength." Cars and trucks, he notes, have gotten lighter and stronger over the years as technology has improved, and the pipeline will be robust as well. The difference between what's normally required and what TransCanada proposes, he says, is only about the thickness of a compact disc.

As East Texans mull the pipeline, the Gulf oil spill is on many people's minds. "You saw the disaster in the Gulf. Admittedly, you should not have a disaster of that magnitude on land," says Zeb Zbranek, D-Liberty, an attorney in Liberty who served as in the Texas House for 10 years. But, he adds, some areas of East Texas, like wetlands, would be especially sensitive to a leak. "If you do have a busted pipeline, you could have some irreversible damage," he says. The pipeline, which will have a 50-foot-wide permanent right-of-way, will run just upstream of the Big Thicket National Preserve in Hardin County, according to the Sierra Club.

Prescott dismisses such concerns. "Pipelines are the safest way to move petroleum products from point A to point B," he says, adding, "In some ways it's apples and oranges to compare pipelines and oil rigs in the middle of the Gulf."

Environmentalists are not convinced. Just recently, Hernandez of the Sierra Club notes, the 800-mile Trans-Alaska pipeline was shut down for a few days due to a small (5,000 barrels) oil spill. Two different natural gas pipelines also exploded in Texas this week; the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has recorded 125 "incidents" involving the oil and gas industry's pipelines in the last five years.

The new project, she says, carries "no guarantee that it will be safely monitored or regulated."

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/TxTrib-Staff_0013_GalbraithKate.jpg)