Dying on the State's Dime

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/20100526-DSC_6152.jpg)

A gaunt old man, thick with whiskers and stricken with dementia, writhes under the covers of his bed. Down the hall, doctors monitor elderly diabetics with recently amputated limbs, medicate terminal cancer patients shuffling by with walkers and tether shivering dialysis patients to blood-cleaning machines.

Despite the pacing guards, the handcuffs and the bars on the windows, the geriatric and medical wing at the Estelle Unit in Huntsville looks more like a nursing home than a maximum-security prison.

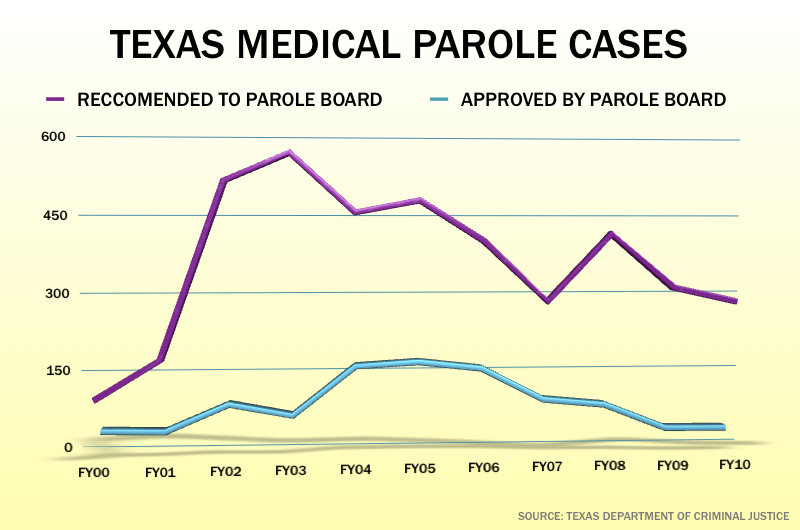

Prison doctors routinely offer up the oldest and sickest of these inmates for medical parole, a way to get those who are too incapacitated to be a public threat and have just months to live out of medical beds that Texas’ quickly aging prison population needs. They’ve recommended parole for 4,000 such inmates within the last decade. But the state parole board, which makes the final decision on “medically recommended intensive supervision,” has only agreed in a quarter of these cases, leaving the others to die in prison — and on the state’s dime.

Texas’ “geriatric” inmates, classified as those 55 and older, make up just 7.3 percent of Texas’ 160,000-offender prison population. But they account for nearly a third of the system’s hospital costs and make three times as many visits to prison medical departments as younger inmates. Elderly inmates have average annual hospitalization costs of $4,700, compared to $765 for inmates under 55. In total, providing inmate medical care costs the state correctional health care system — already facing hundreds of employee layoffs amid a budget shortfall — nearly half a billion dollars a year.

Parole board members say they’re faced with the difficult task of determining whether an inmate is still dangerous and must err on the side of public safety. “You can be sick, have an illness or a disease, and still be a threat,” said board chair Rissie Owens. “Our decisions aren’t based on numbers, on quotas. And we feel like we’re making good decisions.”

But criminal justice and prison funding experts say leaving elderly, terminally ill inmates to waste away behind bars is often unnecessary and exorbitantly expensive. Those costs would be shared with the federal government if the offenders weren’t in state custody.

“These are totally incapacitated inmates, terminally ill inmates, inmates on respirators, who are not paroled at a huge expense to the state and hardship to the inmate’s family because of the nature of a crime they may have committed 20 or 30 years ago,” said Sen. John Whitmire, D-Houston, who chairs the state Senate’s Criminal Justice Committee. “I think it’s largely for political reasons.”

The cost of care

While the total prison population in Texas isn’t growing, it’s quickly aging. The ranks of geriatric inmates are rising by about 6 percent every year, frightening the budget writers who have to figure out how to pay for them. Health care costs are rising too: The average daily medical bill for Texas inmates grows about 4 percent every year — which is low, compared to some states.

The sickest inmates can each cost the state up to $1 million a year in health care costs. If these same inmates were living in nursing homes or hospice facilities, the federal government — through Medicaid — would pay two-thirds of the cost and save Texas taxpayers up to $50 million a year, according to state projections. If the offenders are eligible for Medicare, the feds would pick up the full tab. “We could be transitioning them to some other facility where state taxpayers wouldn’t have to bear the full health care cost,” said Marc Levin, the director of the Texas Public Policy Foundation’s Center For Effective Justice Director, who suggested special nursing homes or hospice centers monitored by parole officers. “It’s a real opportunity to identify some savings without doing anything to endanger public safety.”

But despite the fact that the national one-year recidivism rate for older offenders is miniscule compared to that of younger offenders — 3.2 percent for inmates over 55, compared to 45 percent for inmates between 18 and 29 — an April report by the VERA Institute of Justice, a nonprofit criminal justice policy group, found that the 15 states that allow medical release rarely use it. What stands in the way? Political repercussions, complicated review processes and limited eligibility, the researchers found.

Getting Texas inmates released on medical parole is no easy task. To be eligible for it, an offender can’t be on death row or be serving life without parole, and must be either terminally ill (six months or less to live) or require intensive long-term care, said Dee Wilson, director of the Texas Correctional Office on Offenders with Medical or Mental Impairments. Sex offenders must effectively be in a vegetative state for consideration.

If inmates qualify, the office, in conjunction with the Correctional Managed Health Care Committee, recommends them for medical parole, then submits them to the seven-member Board of Pardons and Paroles for a decision. “It’s all about how long you have to live, and what your prognosis is,” Wilson said. “You can have a terminal illness but still be fully functioning.”

Dying behind bars

The parole board, in turn, relies on a pre-existing condition threshold of sorts. If an inmate with a particular illness commits a crime, Owens said, it’s unlikely he or she will get medical release for that same diagnosis. Some inmates with multiple amputated limbs may look incapacitated, Owens said, but managed to commit their crimes that way. Of the roughly 4,000 inmates prison health officials recommended for medical release in the last decade, the parole board turned down nearly 3,000.

In the last fiscal year alone, more than 440 Texas inmates died in prison. Thirty-one inmates who’d been recommended by medical staff for release died while awaiting the parole board to take up their case; another 26 died after the parole board rejected them for release. Twelve inmates were approved for medical parole but died before they could be sent home.

“There are documented cases where individuals had days or weeks left to live” and were rejected for medical parole, Whitmire said. “I saw no reason why they shouldn’t be paroled so the family could make plans for their funeral.”

Texas is not the only state struggling with skyrocketing prison health care costs and concerns around medical release. Between 1999 and 2007, the number of inmates 55 or older in state and federal prisons grew by more than 75 percent, to 76,000. To date, more than a dozen states have units set aside for elderly inmates; eight have dedicated hospice facilities. Estelle has an impressive medical facility, with a bustling emergency room, high-tech telemedicine equipment and a team of nephrologists that perform 1,800 dialysis treatments a month — sometimes on aggressive or unstable inmates.

“From a medical perspective, I’m comforted that [offenders are] getting a level of care they may not be getting on the street. On the other hand, we’re about to un-employ 363 people,” said Dr. Owen Murray, the chief physician for the University of Texas Medical Branch’s correctional managed care program, which oversees health care for the majority of Texas’ prisoners — and is facing layoffs this summer. “Are there other strategies to reduce our costs? And how do we prevent having to build more expensive units in the future?”

Charles Dill, a 71-year-old offender who started a 20-year sentence in 2000, has been hospitalized multiple times himself for costly heart problems, including getting stents for his carotid arteries. He’s befriended several elderly inmates in Estelle’s geriatric unit, only to watch them die on the ward.

“I’ve seen several of these guys drop over dead,” Dill said, gesturing across a prison dorm room of prosthetic limbs and wheelchairs, adult incontinence products and white-haired men in Coke-bottle glasses. “I guess they completed their sentence.”

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Ramshaw-Close.jpg)