New Houston Hurricane Plan Stirs the Pot

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2016/03/09/SHIPCHANNEL_SEAWALL1176.jpg)

A new proposal to protect the Houston area from hurricanes is reigniting controversy, and potentially diminishing the odds that a consensus will emerge anytime soon on the best plan to safeguard the nation's fifth-largest metropolitan area.

Since Hurricane Ike in 2008, Texas scientists have pushed several different plans to shield the region, home to the nation's largest refining and petrochemical complex, from devastating storm surge.

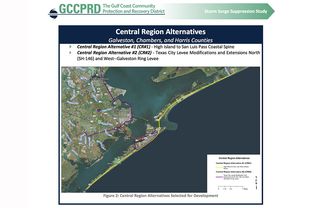

Some accord emerged in recent years around a $6 billion-to-$8 billion Dutch-inspired concept called the “coastal spine,” creating some hope that state and federal lawmakers may have a single proposal to champion before the next big hurricane hits. The concept — an expanded version of another, dubbed the "Ike Dike" — is designed to impede storm surge right at the coast with a 60-mile seawall along Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula. A massive floodgate between the two landmasses would be closed ahead of a storm. Several dozen communities have endorsed the coastal spine — conceived at Texas A&M University at Galveston — along with some state lawmakers, the Texas Municipal League and at least one major industry group.

But a six-county coalition studying how best to proceed now says a 56-mile, mostly mainland levee system — several components of which have been proposed before by other entities — would provide a nearly equivalent level of protection while costing several billion dollars less. The catch: several Houston-area communities on the west side of Galveston Bay, including Kemah, La Porte, Seabrook, Morgan’s Point and San Leon, would be left outside the dike.

And officials from those communities say that is unacceptable.

“Just the fact that it’s mentioned — I take it as a serious threat,” Seabrook Mayor Glenn Royal said.

The $3.5 billion proposal by the Gulf Coast Community Protection and Recovery District, unveiled in a report last week, calls for expanding and extending an existing levee around Texas City northward along State Highway 146 and westward to the community of Santa Fe. The recovery district's plan also calls for placing a "ring" levee around the entire city of Galveston to protect it from storm surge. (During hurricanes, the island gets hit by surge once from the front and a second time from the back when surge that reaches the mainland recedes.)

The part of the proposed levee closest to Texas City — home to three major refineries — sits right on Galveston Bay, but most of it is set back from the water, meaning the communities between it and the bay are left unprotected.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and a hurricane research center headquartered at Rice University also have proposed raising or building a levee along SH-146 and installing a bayside levee to protect Galveston, but the concepts have never gained much public support. The SH-146 proposal, in particular, has met staunch opposition from the communities located between the highway and the bay — a sentiment that’s not lost on the recovery district.

“It’s not the best — we know that,” said Col. Chris Sallese, coastal programs manager at Dannenbaum Engineering, of the proposed levee system at a Tribune event last week. The recovery district hired the local firm with a $4 million state grant to study how best to protect the greater Houston area from hurricanes, with work beginning in 2014.

But Sallese, a former commander of the Army Corps' Galveston District, also said there are legitimate questions about the high cost of the coastal spine and the environmental impact of installing a massive floodgate between Galveston and Bolivar to help keep storm surge from entering Galveston Bay. He said a big concern is that it would greatly hinder the flow of water between the bay, one of the region’s most productive estuaries, and the Gulf of Mexico. That could "change the hydrodynamics, morphology, and water quality of the bay," according to the recovery district's report.

That could mean non-compliance with federal environmental regulations such as the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970, Sallese said. Assuming that any storm surge protection project will be federally funded, that would mean the project could not proceed.

Sallese said other proposals that have called for placing massive floodgates at other places in the bay to block surge face similar environmental concerns, so the study team wanted to propose something gate-free for the public and recovery district board to consider and compare to the coastal spine. And Sallese said the residents who weighed in on such a plan at a series of public hearings last year soundly rejected the idea of installing the entire levee system along the bay-front, which is lined with high-dollar homes and recreational areas.

"We're not trying to take anything away from the coastal spine. We’re just trying to say: If you could not build it, what could you do" instead, said Sallese, noting the study team could not delve any further into environmental impacts because of limited funding.

Asked about past opposition to SH-146 and ring levee concepts, Sallese said no one had ever seriously examined their feasibility or cost before.

According to the recovery district's report, conducted using Army Corps standards, the levee system would provide more than $1 billion in annual benefits, and — at $3.5 billion — cost much less than the coastal spine, which Sallese's team estimated would cost $5.8 billion and have about the same annual benefit.

The levee system therefore has a cost-benefit ratio nearly twice as high as the coastal spine, according to the report.

But Recovery District President Robert Eckels, a former Harris County judge, stressed that the study team found that the coastal spine's cost-benefit ratio is high, too — and that the Army Corps' cost-benefit analysis doesn't account for social and other impacts, including economic and flood damage to areas left outside the levee system.

The recovery district will carefully consider those other factors, he said, going on to guess that the recovery district's final recommendation will be "a combination of the two" plans.

Some state lawmakers have said they will champion whatever the district recommends. And the Army Corps will use it as guidance in its own, recently launched study into how best to protect the Texas coast from hurricanes, which is not expected to be done for at least five years.

Army Corps Project Manager Sharon Tirpak said during a recent interview that an environmental analysis will be a big part of the study and is what has been missing from all the research done so far.

"None of the other entities have done any of the environmental work," she said.

But a hybrid approach is a nonstarter for officials in bay-area communities like Seabrook — and the researchers at Texas A&M University at Galveston developing the coastal spine concept who believe it is end-all, be-all to the region's hurricane problems.

"It's DOA, OK?" said Morgan's Point Mayor Michel Bechtel of the proposed levee system, calling it "bullshit."

"It's silly to protect some of the people at the cost of the other people," he said. "And we will not be collateral damage, period."

Texas A&M oceanographer Bill Merrell, who conceived of the coastal spine concept, has been opposed to placing a storm surge barrier anywhere but directly on the coast because he says putting anything farther inland would protect certain areas at the expense of others.

"You can’t come up with anything in the bay that doesn’t hurt somebody," he said. "It's impossible."

Along with the bayfront communities, Merrell said the proposed levee system leaves the western end of Galveston — lined by high-dollar beach homes important to the island's tax base — completely unprotected. And he said it would do nothing to block surge from entering the Houston Ship Channel, a 52-mile shipping lane that juts off Galveston Bay. The waterway is lined with refineries, chemical manufacturing plants and various shipping terminals whose business activity makes up a sizable chunk of the state's GDP.

The levee system "won’t go because of public opinion," Merrell said. "The mayors around the bay aren’t going to let this dike happen — I can assure you."

Sallese's study team will take public comment on both the coastal spine and levee system at a series of public meetings this month before making a recommendation to the recovery district board, which may accept or reject it. A final report with recommendations is expected in June.

As the debate heats up, the recovery district may have an ally in the Severe Storm Prediction, Education and Evacuation from Disasters Center at Rice, which has pushed the SH-146 and Galveston ring levee concepts in recent years.

Center co-director Jim Blackburn also said a combination approach would be ideal.

"We think there is a hybrid out there that is the best of all worlds," he said.

Blackburn's only quibble with the recovery district's report was that it envisioned protection systems for the Houston, Beaumont and Freeport areas not being completed until 2035.

"That’s a scary number," he said. "I think it would be failure on all of our parts if we can’t find out how to get something underway in three to four years — and I think that’s possible."

Disclosure: The Texas Municipal League is a corporate sponsor of The Texas Tribune. Rice University was a sponsor in 2013. A complete list of Tribune donors and sponsors can be viewed here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/Kiah.jpg)