New Education Training to Promote Mental Health Intervention in Schools

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/images/2013/08/16/Teacher.jpg)

Throughout August, The Texas Tribune will feature 31 ways Texans' lives will change because of new laws that take effect Sept. 1. Check out our story calendar for more.

When Josette Saxton was in high school, she wrote an essay about child abuse that was a red flag for a teacher who reached out to offer her help.

“I was just being creative,” said Saxton, who is now a mental health policy associate for Texans Care for Children. “But what if I was someone who was feeling alone and it was a cry for help?”

Starting Sept. 1, more Texas teachers will be trained to offer the kind of intervention Saxton’s teacher did when it is needed. Senate Bill 460, by state Sen. Robert Deuell, R-Greenville, will implement new requirements for mental health intervention strategies in schools that are intended to help teachers reach out to students who show signs of mental or emotional distress.

Until recently, talk about mental health policy in Texas was focused on treating serious mental health disorders rather than on assessing disorders before they escalate without treatment, Saxton said.

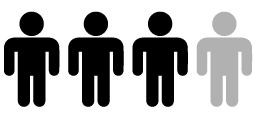

About 288,000 children live with serious mental health conditions in Texas, according to 2010 figures from the National Alliance on Mental Illness. And those students, according to the Alliance, are more likely to drop out of school.

Hoping to prevent many of those students from dropping out, Texans Care for Children and a coalition of other groups that promote mental health and disability awareness, including the Texas Council for Developmental Disabilities and Mental Health America for Greater Houston, urged legislators this year to consider the need for positive intervention programs and for training educators.

Under the new law, school districts will be required to provide teachers, administrators and staff with training on mental health intervention and suicide prevention to help them identify red flags in a child’s behavior and respond effectively.

“We’re not looking for schools to diagnose or treat kids,” Saxton said. The law, she added, is “a good starting place to increase a school’s ability to do a better job of recognizing when a child is having serious mental concerns and then knowing how they can respond in a way that won’t make it harder for students.”

The one-time training sessions could be implemented as soon as the upcoming school year.

The new training requirements will also lead to changes in the college curriculum for aspiring teachers at Texas universities. College students will receive instruction in the detection of mental or emotional disorders before receiving their diplomas.

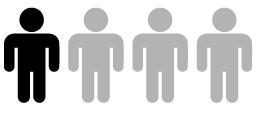

Behavioral management courses are already offered in education programs at several universities, but they are usually limited to students majoring in special education, said DeAnn Lechtenberger, director of technical assistance and community outreach at Texas Tech University’s Burkhart Center for Autism Education and Research.

Universities’ efforts to create additional behavioral management courses for students in general education programs will push the two disciplines to work collaboratively, Lechtenberger said.

The specialized behavioral management courses and training will fall under Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, or PBIS, a program promoted by a federal special education technical assistance center.

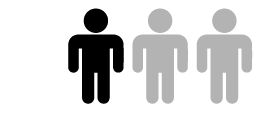

Supporters of the new law also hope the new training will reduce the segregation in classrooms of children with behavioral issues, including mental and emotional disorders.

If teachers are trained to implement methods of intervention that create a suitable learning environment for all students, they hope that students with behavioral disorders will be able to stay in regular classrooms.

“Our goal is that every child is served with a regular curriculum,” said Belinda Carlton, public policy specialist for the Texas Council on Developmental Disabilities.

Carlton said she hopes PBIS training at the college level will change educators’ philosophy “from the ground up,” starting with new teachers.

“Even if we can’t educate every educator already in public schools, if every future educator has the training, we see this impacting on a system-wide level for the future,” Carlton said.

Quick Facts about Children and Mental Health in Texas

Texas Tribune donors or members may be quoted or mentioned in our stories, or may be the subject of them. For a complete list of contributors, click here.

Information about the authors

Learn about The Texas Tribune’s policies, including our partnership with The Trust Project to increase transparency in news.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/profiles/ura-alexa_TT.jpg)